There is a more general problem related to the “what to do with old lab notebooks” that some of us face. It is what to do with our shoeboxes of photos (virtual digital shoeboxes and real ones). And written correspondence. Love letters. Birthday cards and holiday cards that caught our attention enough that we saved them. The trophies, actual physical trophies, or the certificates of commendation for a job well done. Birth and death announcements. Souvenirs of our travels, the mementos of the high points of our lives.

All of them carry great meaning to us, invoking a romantic haze of fond memories from those times and places, for those people and events. Yet those memories are internal to us; they are not shared, even with the persons we may have shared the moment with—at least not exactly. Each of them has his or her own version of those scenes. And they are not shared in the same way with our children, and certainly not their children. Our lives are an abstraction to them. They weren’t even around when the main story was unfolding.

I have come to realize this in the last few years as I have processed the items left behind by my parents after their deaths. I have a high regard for my father’s technical acumen and his many projects. Some of them were to gather and archive family history, others documented his personal interests. He was always an early adopter of technology and embraced digital photography well before I did. He acquired a large collection of both film and digital pictures, organized in shoeboxes and digital folders. He worked to digitally scan historic family photos that dated back to the 19th century.

There is a treasure trove of history here, some even recent enough to overlap with my own, yet I do not find myself compelled to explore it. And therein lies the problem. If I am not inspired to carry forward the artifacts of prior generations, why would I expect subsequent generations to propagate mine?

I take note of the things that I do preserve: a family tree going back to the 1800s, my dad’s ham radio telegraph key that won him numerous awards in the amateur radio circles (but not his corresponding wall plaques), some artifacts from his career developing computers, a campaign flyer from when he was mayor of our small town, some books from his library, mostly for their historical value. The digital photos are held in computer files archived by my brother. The physical photos are also in his keeping, safely stashed in cardboard boxes for some uncertain time, probably for when a subsequent descendant unearths them and wonders who these people are.

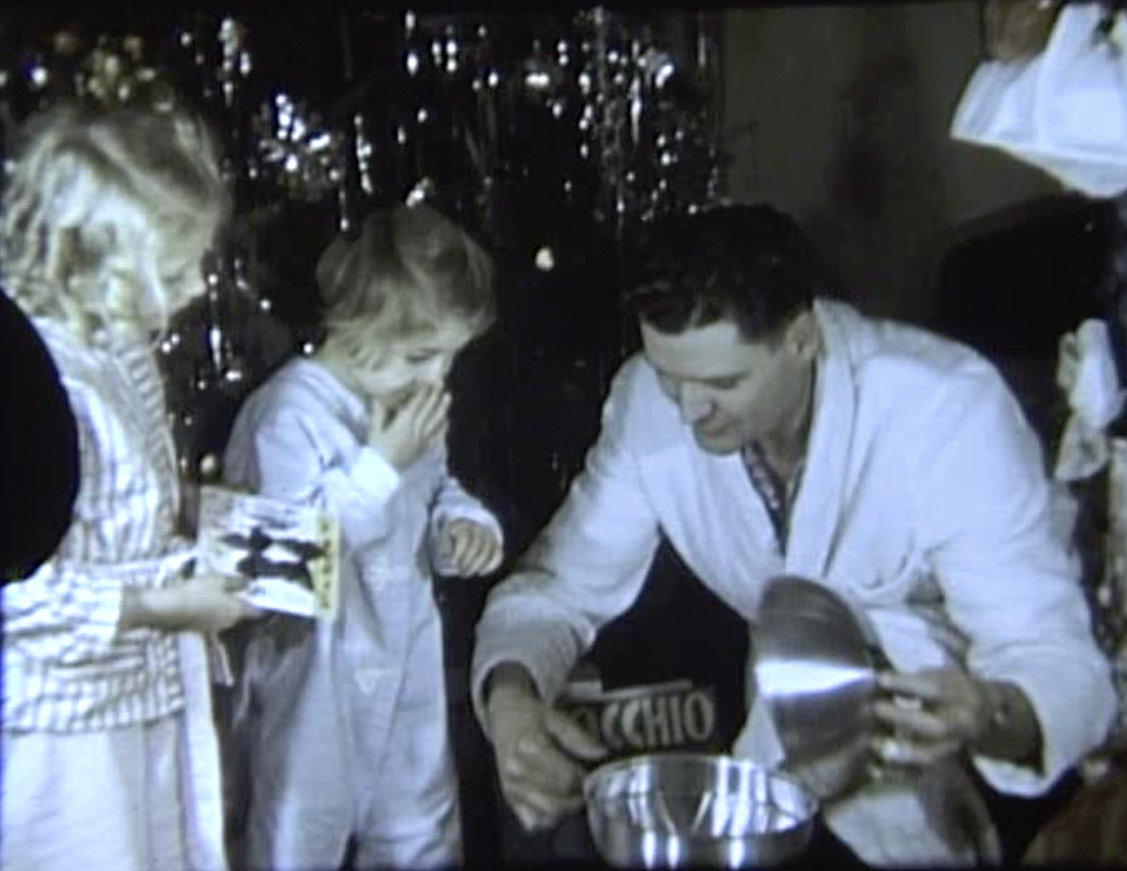

I already possess a few such archives: 16mm movies taken by my grandfathers early in the last century (both were eager technology adopters). Some show old-timey Christmas parties, with unidentified children excited to open gifts, and holiday specialties served at a family dinner table to ancestors whose names I will never know.

What is the value of such items? At one time they captured the experiences of everyone in the scene. When they were alive, they could re-experience those moments and savor the positive emotions they evoked. Now they are all gone, and the rare review of these films is for an audience of descendants with no direct connection, other than the abstract awareness that this was a moment that mattered to some great-grandmother or other such past relative in their childhood. What is my obligation to preserve these films? Are they historical documents or simply notes in the margins along the way?

Technology has shifted the physical nature of our legacies. It has transformed them from physical objects, letters and photographs, to digital files. Digital files held on some memory device that needs a computer to examine it and show us what it contains. These items are not “human-readable”; the information is trapped inside the technology of micro-chips and exotic media. What does that mean for passing the information along?

I notice that there have sometimes been a few members of our extended relatives that take a curiosity in our ancestral past and are eager to gather and collate the artifacts of past generations. They become the genealogists of the family. The internet now makes it easy to establish family trees and connect them to the rest of humanity. Unfortunately, I do not see this genealogist trait in my siblings or offspring. Or me, other than these philosophical musings.

Somehow the begat-connections are unsatisfying to me; I want to know more about the life and times of my ancestors beyond just their names. This has not been practical before; the recordings of life were sparse— entries in family bibles, formal portraits, and exchanged letters (if preserved). Today we have a wealth of recordings, on computer files, and now on a “cloud” of stored information. I am told that sociologists and archaeologists are already analyzing the contents of Facebook entries from members who have since passed away, for their cultural content.

I will continue to struggle with what to do with the various items I have accumulated over a lifetime. Some of them will remain in the “distributed computer museum”, that most of my colleagues contribute to in a corner of their basements, but other things will see the light of day as I review them and decide whether they are worth sharing as I make that decision: “Do I keep this item, or do I want the space it is taking up?”

Pingback: What to do with (really old) home movies? | Thor's Life-Notes