The American Southwest is an amazing, mysterious, and visually stunning place. I’ve had a fascination with it my whole life, and make excursions whenever an opportunity arises. A few years ago, Poldi and I discovered an area in New Mexico with remarkable geologic features: badlands, hoodoos, and petrified wood! It was the Bisti Wilderness Area, held apart from private and reservation land by the Bureau of Land Management for the benefit of the public. It is only very lightly “managed” by the BLM. There are no visitor centers, no picnic areas or campgrounds, and no trails. There is a small parking area at the end of a difficult dirt road, marked by a signpost and featuring an outhouse.

Despite the lack of trails, we were able to follow the breadcrumb descriptions posted online by a photographer who explores Bisti for its photogenic subjects. We located and visited the Alien Egg hatchery, a 30-foot-long petrified log, and a hoodoo village. In the years since, we have wanted to return and explore more of this fascinating area.

We were able to do so this year. The timing was right—late Spring, before the desert becomes intolerably hot. We both researched and found several more sites with novel features bearing names like “King of Wings”, “Chocolate Penguin King”, and “Alien Throne”. These are not roadside points of interest with explanatory markers; they are deep in wilderness area, accessible to intrepid hikers willing to explore the desert and locate them. Those that are successful bring back stunning photographs.

Those photographs inspired us to consider visiting them. A particularly novel feature, “The Alien Throne”, made me wonder if I could get a picture of it with a night sky backdrop. I read the accounts of others who had made the trip. Maybe it was possible!

After deciding on this photographic target, I needed to find it! There are several levels involved in “finding it”. Navigational dead reckoning by hiking the desert is one level. Based on GPS coordinates, it could be located on a map, but how to even get close? Ideally, you’d drive to the nearest point on the nearest road and hike from there. That seems easy enough if the roads were like the ones you find on state highway maps, identified by number and by road type.

But the roads throughout this area of New Mexico are not like those roads. They range from a regular width of gravel, to narrower washboarded and eroded dirt roads, to pairs of ruts, to a single path indicated only by a slight contrast in vegetation. In fact, they are sometimes not even visible on the satellite views presented on Google Maps. Were it not for the Google label overlay, some of the roads would not be identifiable.

The roads do have numbers, often multiple numbers: state, county, and reservation, each with a distinct designation. Not that it matters. When on one of these back roads, there are few identifying signs showing any number at all.

We had no fewer than four navigational tools to help us. My trusty old standard is a state road atlas, printed as 90 pages of large 11×17 B-size paper sheets bound into a book. This revealed land ownership status and showed details, including unpaved roads, but only down to the officially maintained gravel roads. The lesser roads were not shown at all, yet we needed them to reach our desired access points.

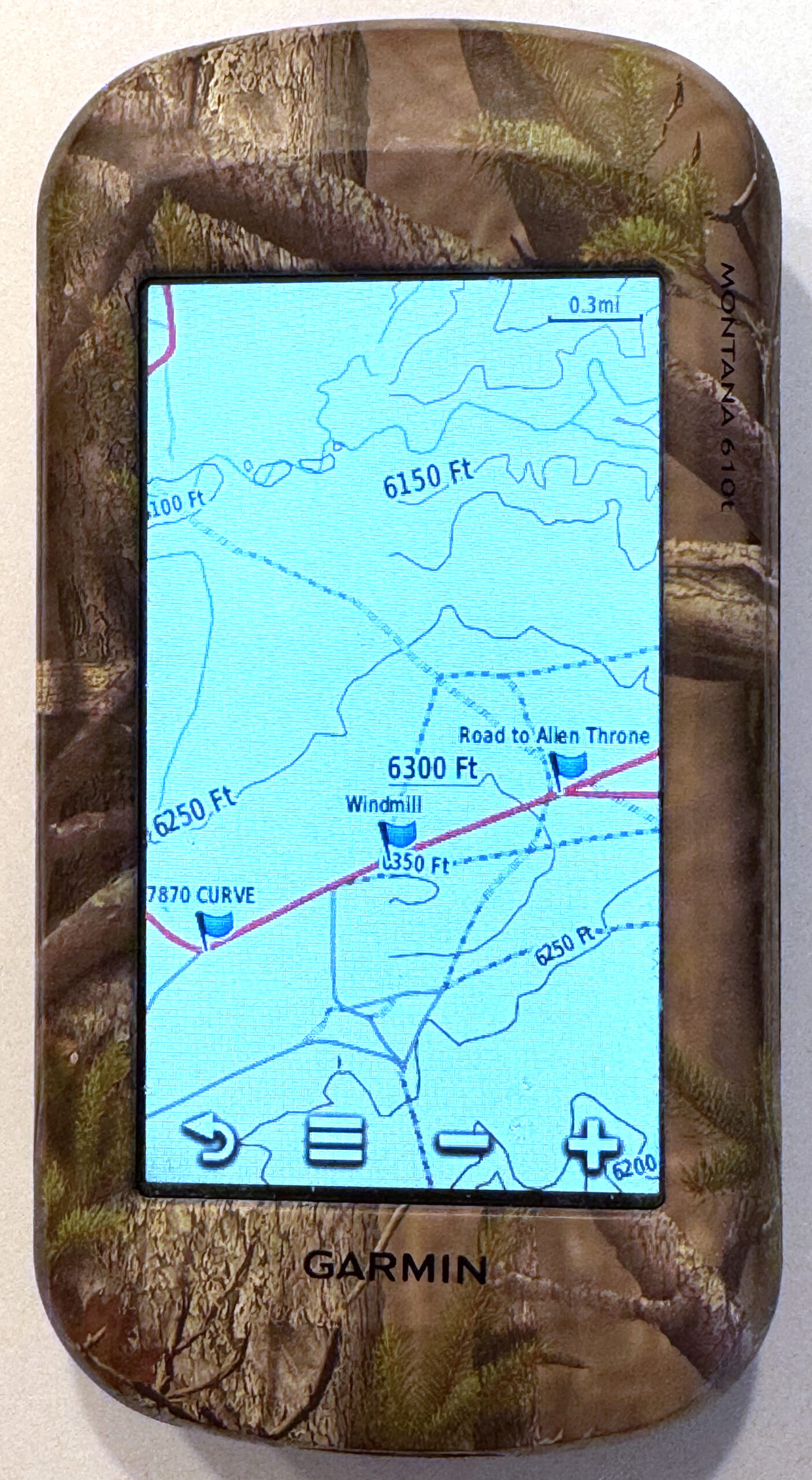

In addition to the paper atlas, we had electronic tools: the mapping applications on our phones, a route display in our car (Volvo calls it “Sensus Navigation”), and a handheld Garmin GPS receiver marketed for outdoor enthusiasts. Having been raised on paper maps and magnetic compasses, I have mixed attitudes towards the electronic tools. I have owned GPS receivers since 2000, starting with a gift from my mother-in-law, who thought it was the height of silly electronic gadgets (but she knew I would love it).

And they are indeed amazing gadgets for locating one’s position on the planet, but less amazing in identifying orientation, and a bit scary in terms of being dependent on batteries and infrastructure (cell phone and satellite signals).

The phone is our main navigational tool on the road because its display and user interface is the most supportive. But it is highly dependent on being in cell phone range. Outside it, one will see a blue dot representing our current location, but in an ocean of gray—the maps that provide context are loaded on an as-needed basis from the cell phone network. No cell tower nearby, no map.

I am also skeptical about its GPS capabilities. My phone does not have the characteristic stubby antenna for GPS wavelengths; how does it see enough sky to get the triangulation data from the satellites?

The car’s Sensus map worked well, but was harder to operate, and suffered some of the same limitations—the map data did not always show. It was better than the phone; I think it has better local storage of map data, but as with all electronic mapping, there is a “level of detail (LOD)” display control that depends on how far you are zoomed in. If it appears that your blue dot is lost in space, not on any route, zoom in some more, and the lesser roads will show up. I often wish I could override the automatic LOD to show more or less of the map detail around me. But even fully zoomed in, we noticed that some of the backroads were invisible—an apparent gap in the map data.

The Garmin receiver (Montana 610t) was the most reliable in getting a signal—it embeds the stubby antenna and it carries all of its mapping data internally, so our location was always displayed and the map seemed to have ALL of the near-invisible back roads. The Garmin, however, suffers from a klunky user interface. I might call it user-hostile, but instead will generously label it as “industrial”. It uses a touch screen that requires a heavy hand, an awkward data entry screen, and the functions are just not intuitive (to me). As a result, even after five years, I barely know how to operate it.

Its greatest weakness, however, is the power supply. GPS receivers don’t need power to transmit, but they must detect very weak signals from satellites hundreds of miles away and make complex calculations on them. The built-in rechargeable battery might last a day or so, but on this trip, it failed to recharge. It could be replaced by lithium AAs, so I now carry spares. Despite this shortcoming, the Garmin was definitely the unit to bring on our excursions into the desert.

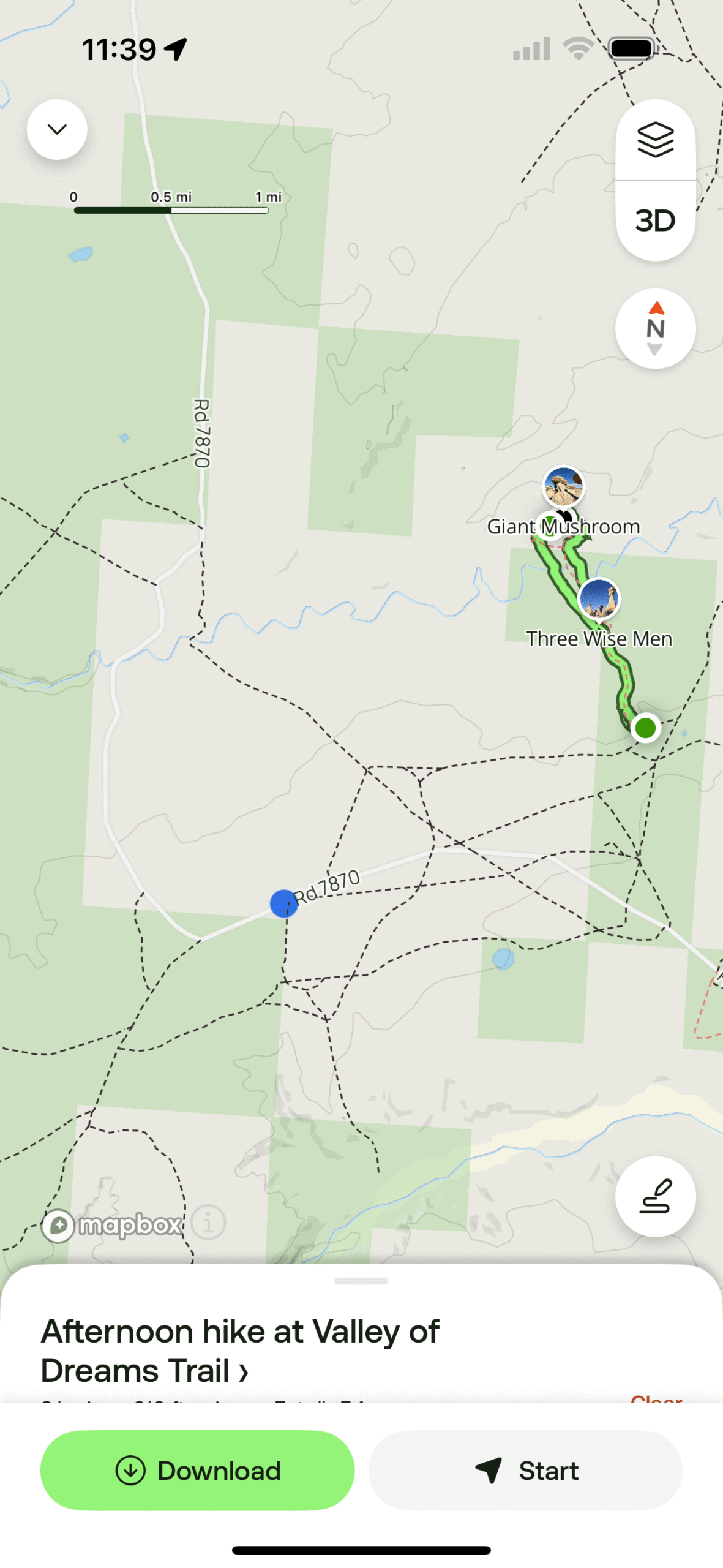

The Garmin was superior in its location display, but it was an app on the iPhone that helped us locate the route to the Alien Throne. Apple Maps and Google Maps are wonderful applications that have changed how we get from place to place. But they are designed for driving, public transport, bicycling, and walking urban streetscapes. There is another application focused on hiking in backcountry settings: AllTrails (alltrails.com), from a company that caters to those of us who enjoy exploring the many hiking trails out there in the world.

They collect and publish maps for these trails, and they support a community of hikers who report back on their experiences and offer advice and photos. The maps can be downloaded to your phone (while connected), and then are available to show your position while on the trail, regardless of cell phone coverage. It turns out your phone is still in contact with the GPS signals (even in airplane mode—recommended to conserve battery life).

There was a trail in the AllTrails library for the Valley of Dreams. This was the navigational help we needed, not only to find our way through the unmarked desert, but also to find the access point! Although we were not at the trailhead yet, the AllTrails map showed us where we were with respect to it, and the roads (numbered or not) that could take us there!

This is how we located the trail to the Alien Throne. The AllTrails application guided us to an informal parking area. There was a clear trail that started here, but then dissipated onto the sandy washes and scrubland of the desert in front of us.

We had located the trailhead, a wide spot to the side of one of the “pair of ruts” roads in the New Mexico badlands. We marked the location on the Garmin GPS, and returned to Farmington to prepare for a hike the next morning.

The weather was clear the next day, and we were excited about hiking to the Valley of Dreams, but it took 1-1/2 hours to return to the trailhead. The day was heating up as we embarked. We had come for the unusual and novel beauty of the desert and this trail really embodied it. It was a little over a mile to reach the area of wind and water-eroded shapes contained in the Valley of Dreams. On the way we encountered other badland features, previews of hoodoos, dry creekbed washes that hosted flash drainage during rain, and the hardy patches of vegetation: cacti and tumbleweed, that somehow make a life here.

Normally, I estimate a two-mile-per-hour rate while hiking over flat terrain, but for whatever reason (trail conditions? distractions? age?), we took twice as long. There really isn’t a trail here. It is a broad, flat area of desert scrub punctuated by interesting geologic features. Distracted by them, we strayed from the AllTrails route, which, because there is no trail; is just a recording of some person’s path. The application would alert us that we had gone off the trail (“Did you take a wrong turn?”). This was both annoying and reassuring.

We reached the Valley of Dreams around noon and entered a region of highly eroded features, areas separated by chasms and gulleys, clearly carved by water, but completely dry today and most days. We found ourselves off the prescribed route and trying to figure out how to not get trapped in some box canyon. We climbed out of one and into another, but eventually found (or think we found) a feature we had read about: the giant mushroom.

And then finally, the Alien Throne! It evoked a sense of both awe and less. As large as it was, sitting amongst its peers in this setting of similar thrones, it did not match the scale that we had cultivated in our minds’ eye from the photos we had seen. Yet it was unique, so eroded by the elements that its supporting column had been eaten through, and the penetrating holes provided viewports to the vista behind. We marveled at it, took photos from all angles, some selfies, and then had lunch under it!

The heat had suppressed our hunger, but our thirst was unquenchable. Electrolytes had fueled our passage to this point, and now apples and grapefruit were the preferred lunch nutrition. We slowed down, caught our breath at this elevation (7000 ft), and enjoyed a moment in the sparse shade of this alien monument.

I was scouting for potential nighttime compositions when I noticed that I could no longer read my position on the AllTrails map on my phone. It had gone dark. Yes, it was high noon in broad daylight in the desert, so I expected the display might be hard to see, but this was significantly dimmer than I had experienced during the hike to this point. The brightness setting was maxed out, but only a faint image, too dim to read, showed itself. The AllTrails app, which up to now had surpassed my expectations, had suddenly failed. I tried various help-line-advice type tricks, like stopping and restarting the application. I shut down every other application that might be running in the background, but the problem persisted. Finally, I shut down the entire phone and restarted it.

A few minutes later, the phone came back to life, the display once again readable. I was relieved. We were never in any danger; it was just a reminder of being out on a technology limb. And in fact, a few minutes later, the display dimmed again, rendering the AllTrails guidance once again useless.

Later, I would learn that this was not an AllTrails problem, but rather a “feature” of the iPhone platform it lived on. When the operating temperature exceeds a certain threshold, the phone cuts back on its power, the display being a big part of it. Even though my body temperature is regulated, and the phone is not even trying to transmit while in airplane mode, evidently sitting in my pocket, or in my hand during a hike at noon in the New Mexico sun was too much for it, and it went into a lockdown safe-mode.

Fortunately, we had our printed maps. They didn’t need batteries, and we could read them even in bright daylight. Although we were never in danger of becoming lost or unable to return to our car, we really wanted to find the remaining cool features in the Valley of Dreams, so we set out from the Alien Throne to find items with names like The Turtle, Petrified Log, and the Chocolate Penguin King. We somehow managed to locate them using our stone-age technology.

We eventually found ourselves back at the entry point to the Valley of Dreams and headed back to the trailhead. Poldi, making the calculation that a straight line was the shortest, led us across the desert in a beeline, never mind the snakes and cactus. She knew that there was a beer packed in an ice chest waiting for us in the car.

It was an exhilarating day, one that we will be adding to our life highlight list.