The next day’s weather was a repeat of the previous: partly cloudy, occasionally overcast, threat of rain, but then open periods of bright sun. Alongside the coffee vendors, protective canopies were set up for astronomy-related businesses and causes. Artists, photographers, telescope and accessory retailers, social and political organizations: all had the equivalent of a wilderness storefront along “vendor row”.

There was also a huge semi-cylindrical meeting tent where presentations were made by various guest speakers, and where a swap meet occurred during the pre-noon hours. This was Saturday and, not having to go to town for any urgent repairs, I wandered through the swap meet, visited the vendors, and planned which presentations I would attend.

Something that surprised me on arriving at Table Mountain was the large number of families present. Not only spouses, whose tolerance of their partner’s nighttime passions extended to accompanying them to a remote location with no amenities (bring your own water), but also children. Many of them. Their play lent a musical high note to the overall sound mix.

This seemed to be an important part of the star party, anticipated and planned-for. There were organized activities for children that kept them busy most of the day, and those who could stay up and participate in the evening viewing were always welcomed.

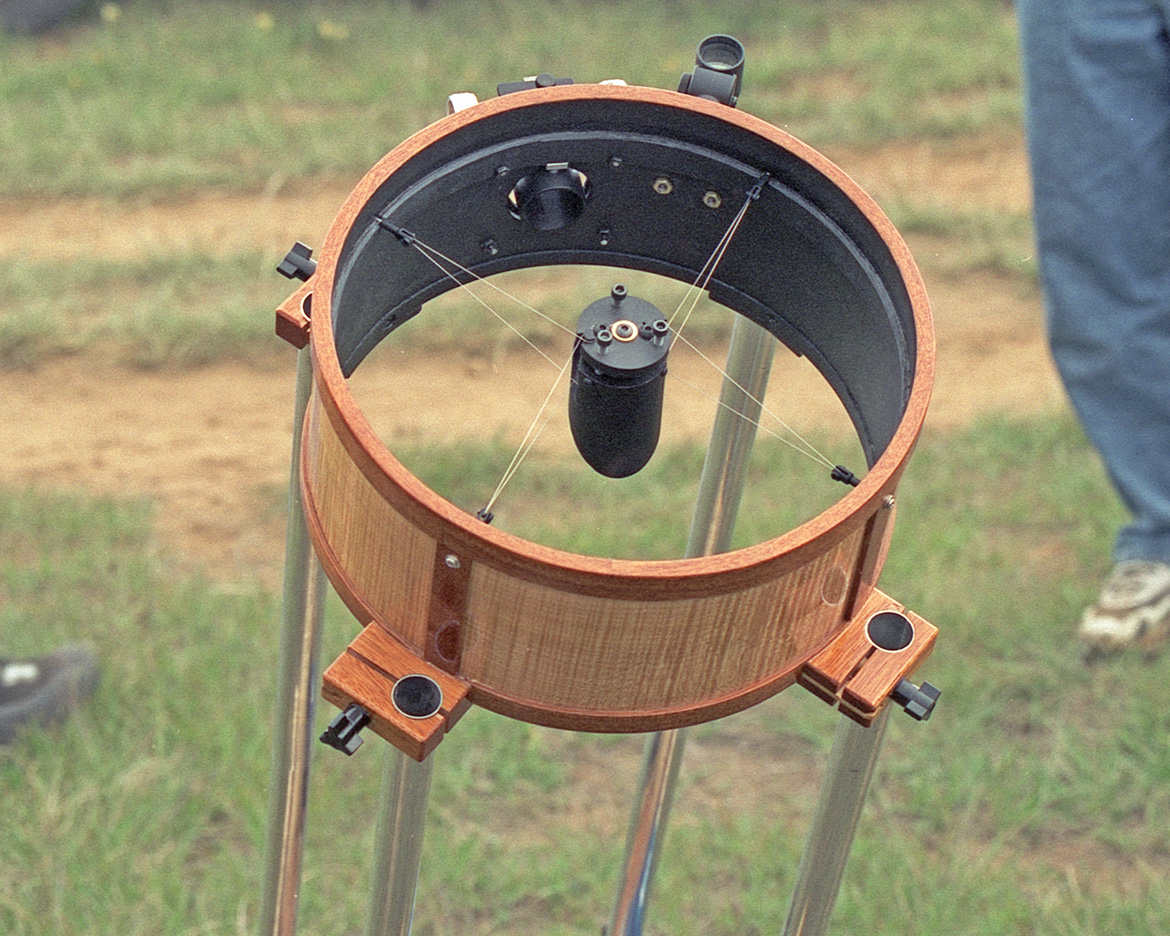

Among the daytime activities planned for the adult stargazers was a showing of craftsmanship. I’ve often felt that there are two kinds of astronomers: those that have a fascination with telescopes and optics, and those that have a fascination with what can be seen with them. Amateur astronomy accommodates both types, and I got to see the beautiful workmanship and clever design work of the former at the amateur telescope-making competition. Some remarkable features were shown: a rotating secondary cage, a 12-inch Dobsonian that collapsed to an-under-airline-seat package, delicate custom designed wooden inlays that gave a unique style to these beautiful instruments. They were all on display in the morning as the judges reviewed them.

The meeting tent was apparently new to the TMSP, purchased from registration fees of earlier years. The audience brought collapsible camping chairs and assembled on the grassy floor of the big room. The presenters could show slides and video because the tent was opaque and kept the space dark when the door was closed. Unfortunately, it kept the room dark at the expense of heating it up, at least when the sun was at full strength.

I learned this while attending one of the presentations, a description of how the initial problems with the Hubble Telescope inspired a wave of software development that could correct the optical aberrations in its images. The software methods could also fix images from other telescopes, like amateur telescopes looking through the full thickness of the atmosphere. Imagine that — getting images from your personal telescope that looked as good as those from the Hubble! To me, a guy trying to get presentable pictures from his telescope, this was fascinating stuff. I recognize that this is not everyday fare for most, but the people at this star party were a rather skewed sample of interests, and I was not alone in finding this captivating.

I had the chance to meet quite a few other amateur astronomers at this gathering. One of the most enjoyable encounters was with a couple from Seattle, Mark and Carrie. They had arrived just behind me in a Volkswagen Eurovan, a vehicle I was beginning to suspect was a better choice for my intended travel style than my aging minivan. Beyond the personal tour of their van, I found out that Mark was at about the same place on the learning curve of astrophotography. Even though his equipment was different, using CCD image sensors instead of film, the obstacles for making good pictures are the same: good focus and good tracking. Carrie was an adventurous partner in their activities, and both were accomplished rock climbers, hikers, skiers, and world travelers.

As the hours moved into the afternoon on Saturday, there was a gathering of the entire population of the mountaintop. The high attendance was generated by a must-be-present-to-win raffle of astronomy-related prizes ranging from books and calendars to eyepieces to entire telescopes. Before the winners were announced, other items were covered. We found out that over 1300 people had attended this year, an enormous number speculated to have been even higher if the weather had been solidly clear.

We also learned about the close-call in having the star party at all. Earlier in the week, a forest fire had started, perhaps caused by lightning. The smoke had been seen by some eagle-eyed residents of Ellensburg, and a group of volunteers had rushed up the mountain and somehow been able to contain it and extinguish it!

The winners of the telescope-making contest were announced. There were a number of categories, but not enough to award all of the talent that was evident in the work.

Acknowledgements were made to the organizers of the star party. As the committee members were identified and applauded, the Port-O-Let tank truck rumbled through, having emptied and replenished the portable toilets that were installed at critical sites throughout the grounds. A thunderous cheering let loose. There are a million details to making a star party of this scale successful, and this one was not overlooked.

An appreciated feature was the meal service. I was pleased to be able to register for these meals, freeing me from finding and preparing my own campground class food. A couple hundred other attendees felt the same way. Not every star party detail was without problem however, and one of them was the unanticipated properties of propane when burned at high elevations. The throughput of the grills and stoves was significantly reduced, and this created bottlenecks in the delivery of fully cooked food to the hungry masses. The Saturday dinner menu of chicken and baked potatoes was a nice finale to the meals served on the mountain, but the serving line extended for well over an hour as the energy-soaking potatoes, starved by the low-energy fuel, became the rate-determining step.

The line did not become unruly; we spent the time comparing notes on what we had experienced at this star party and how it compared to previous years. This did however detain me from an activity I had planned: climbing the trail to Lion Rock to watch the sunset and photograph the young moon. Trapped in the food line, I didn’t dare leave and lose my long-held position in it, but the sun wasn’t going to be rescheduled.

My inertia kept me in the line, and I relished the food, rapidly, when I finally received it. I hastily assembled a tripod, telescope and camera and started the short but steep hike up to the end of the mountain road.

Lion Rock is the name of the spectacular overlook at the end of the road. From here one can see Mount Rainier, Mount Stuart, and the entire Stuart Range. I found it to be a popular place: couples, kids, and sunset photographers all lingered here after what must have been a beautiful sunset. They were a bit quizzical when I started to set up my gear, but the bands of clouds were brilliantly lit in red and purple shades, still a legitimate scene for an after-sunset shot. But when I started asking if anyone had seen the moon set yet, there were blank stares.

I had figured that the moon would be quite close behind the sun, but I didn’t know exactly how close. The new moon had occurred the day before, so in principle, it should be 1/29th of a full circle away, or about 12 degrees, or about 50 minutes behind. But I didn’t know exactly when the new moon condition had happened, I was in a different time zone and my charts were from a different location (Minneapolis). There was a wide margin for uncertainty!

I scanned the openings between the cloud banks hoping to find it. The sky continued to change color, but with no obvious crescent visible. I recruited the others to look, but they were unconvinced that there was anything to look for. Eventually, after another 10 or 15 minutes of scrutiny, I found it! A hairline crescent, gently breaking the smooth blue-green sky in the west. Averted vision, an astronomer’s trick to find faint objects in the dark by looking just slightly to the side of it, also works in the day and helped reveal its location. I pointed it out and eventually convinced a few others that there really was something there. They showed it to more onlookers and soon we were all gazing at this faint feature of the sky.

As the sun dipped further below the horizon, the sky darkened, and the thin crescent became somewhat easier to see. I set up my telescope to get a closer look but discovered that I had left behind my eyepieces, and the camera had no viewfinder and no way to get it in focus to take my moon shots. This was a big disappointment. I had made it this far, the weather had provided a break in the clouds, I was at the right place and time, but was missing a critical part to actually take a picture. This is more common than I would like to admit, but the truth was I had come this far to take pictures of the moon, and I had blown it.

Among the folks at Lion Rock were a couple of astronomers with big Dobsonian telescopes. While I was scrutinizing the western sky for the moon, they were trained on Mars, to the south. Mars had recently been at its closest and brightest in many years and was keeping these astronomers busy and preoccupied with their early evening view of it. When my own telescope failed, my small group of moon-viewing followers turned to these unsuspecting observers, assaulting them with questions about whether they could see the moon.

“The Moon!?”

“The Moon!?”

Completely surprised that the moon might even be visible, the two astronomers swiveled their “light cannons” on their turrets to the west and focused on the setting moon. We all took turns looking and marveling at the razor edge of this beautiful crescent.

There are many cultural calendars that are based on the lunar period of 29-1/2 days, most famously the Islamic calendar comprising twelve such lunar months. Each month begins upon the sighting of the new moon. On the 29th day of the old month, trusted Muslim observers are assigned the task of detecting the new crescent. If it is not actually visually sighted, the month continues for another day. As a result, the Islamic lunar year usually has alternating months of 29 and 30 days.

If the young moon is less than 12 hours old, it will be nearly impossible to see because it is still so close to the sun (the youngest moon ever seen is 11 hours, 40 minutes, by an observer in Iran). But because of differences between observers and sky conditions and geographic location, the Islamic month will differ among Muslim countries. And because twelve lunar months is eleven days short of a solar year, the Islamic religious events such as Ramadan, drift across our Gregorian calendar.

Pingback: 2.3 Rainy Days, Espresso Nights | Thor's Life-Notes

Pingback: 2.5 Exodus | Thor's Life-Notes