I decided that to become more skilled, I would need my own torch and materials so I could practice and make as many mistakes as needed to acquire a specific glass-blowing skill. I found a torch on eBay, some hoses and fittings on Amazon, a tank of propane from my barbeque grill, but then had to figure out an oxygen source. I also needed an exhaust system so I wouldn’t asphyxiate while heating glass from my propane-burning torch.

The exhaust system was simple in principle, but of course, the actual implementation was not. I wanted to create a “glass working station” in a corner of my garage/workshop—a recently built structure with a 10-foot high ceiling with no explicit ventilation. This has already been a limitation when I wanted to work with paints, adhesives, or solvents that required a ventilated area, so I welcomed the excuse to create a ventilation zone for my shop.

Professional paint and chemistry booths are expensive, so I looked for kitchen exhaust hoods. I discovered that they have an enormous price range which depends almost entirely on the current popular style and appearance of the sheet metal hood, and almost nothing on the exhaust rate of the fan. The typical kitchen exhaust rate was less than I wanted anyway, so the fan didn’t matter—I would be replacing it. I really wished I could buy the exhaust hood sans fan motor, but they are rare. And when you find them, they cost the same or more. It’s the external visual style you are paying for.

I found a low-cost, unattractive but functional, kitchen exhaust hood with a low-power motor that I could replace with one that was more capable. It seems a huge waste, but these are the tradeoffs in the DIY world.

The air exhaust had to go somewhere of course. This usually means penetrating the roof with a chimney or vent. For this, I was accidentally lucky.

When I designed my “Garage-Mahal”, I contemplated how to keep it tolerably warm and cool through our Minnesota seasons without active heating or air conditioning. I wanted to be able to work in it during the summer blast, and also to keep liquids (paint, solvents, and humans) from freezing during the winter. To this end, I specified that vents (air register openings) be installed between the studs to provide air intake from outdoors to indoors, and air outflow from indoors to out. It wasn’t all that carefully thought out, but it resulted in exit vents near the ceiling. One of them turned out to be perfect for directing the output of the vent hood.

I spent several days installing the vent hood and upgraded fan motor with a combination of fittings, adapters, and ducts to create my exhaust zone. But now I have it. I can remove air at 500 cubic feet per minute from the interior of my garage/shop. I was pleased. And then my workshop-savvy friend Dave asked “Where does the replacement air come from?”

Of course at some level I knew about this concept. Air leaving the building must be replaced by air entering it. I just hadn’t considered it. If the garage was truly “tight” there would be no incoming air, the internal air pressure would drop, and eventually, the vent motor would stall in its effort to move the air from inside to out, and my goal of removing the toxic products of burning propane would fail. In this scenario, I pass out and die.

Fortunately, my garage is not tight. It has the accidental vents I specified, and they are all connected between inside and outside (except for the one I stole for the exhaust fan). The replacement air will come in from outdoors. This is a great outcome, except for the nuisance that, in winter at least, it will be considerably colder than the air it is replacing. My tolerable shop temperature of 50F will be replaced by air that is sometimes below zero.

Oxygen

The bigger obstacle for making my glass working station was providing a source of oxygen. I thought that maybe I wouldn’t need the hassle of managing oxygen tanks and regulators—I would just use air, which is 20% oxygen, the rest being neutral nitrogen. But experiments indicated that my torch did not work with air—the necessary flow was too high and the flame was blowing itself out. I learned that air can be used, but specialty torches are needed, and the flame is not hot enough for the satisfaction of most glass workers.

Many glass workers (also called “flame workers” or “lamp workers”) use a machine called an oxygen concentrator. It is used to provide oxygen to patients who need more than the 20% available from the air. It uses a pump and filtering system to bring the concentration closer to 80%. This is great for the patient, and there is a market for rebuilt used concentrators since new ones are expensive. This is convenient for the glass worker—it is a supply that won’t run out. But it comes with a few drawbacks: the maximum flow is 5 liters a minute—not quite enough for larger projects, and… they are noisy.

Dave had opinions about this, strongly suggesting that I avoid the concentrator, in favor of just entering the world of welders and metal workers, buying an oxygen tank, and refilling it as needed. With his experience in welding torches, foundries and forges, this was no big deal to him. To me, it meant a big expense for the tank, and figuring out how to schlepp it around to get it refilled—the pressurized cylinders are heavy!

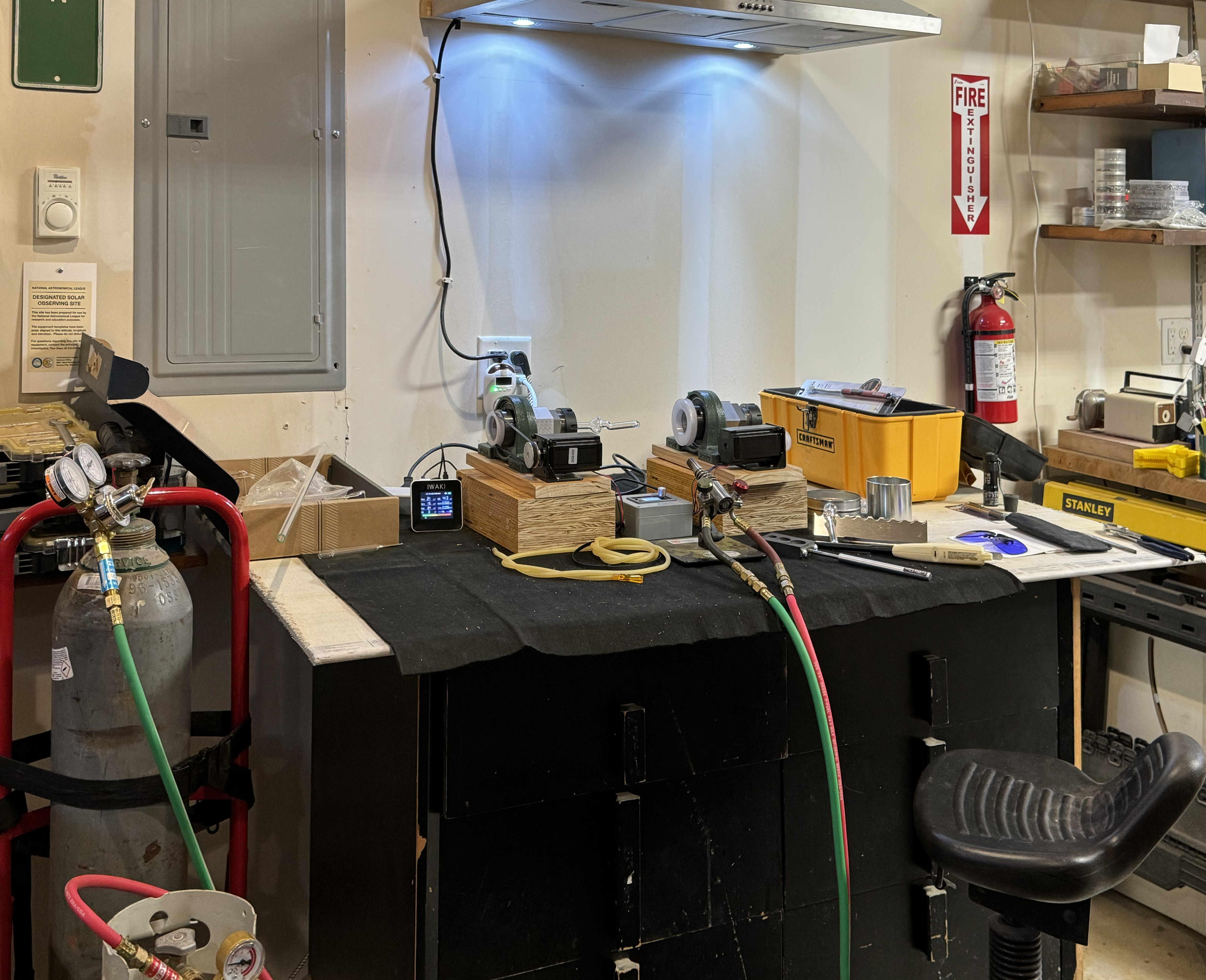

In the end, I decided to follow Dave’s advice and establish an account with a nearby welding supply company. They had a selection of tanks that I could lease for five years. I picked one that was the largest I could still lift into the back of my car. To this expense I added a two-wheel dolly to help maneuver it, and a regulator, a necessary throttle so the torch would not be overwhelmed by the pressure of a newly refilled oxygen tank.

I still didn’t have all the stuff I needed. I needed another regulator for the propane. And to get from the tanks to the torch, I needed hoses of some useful length. There are also devices to put in line with the hoses, called “flashback arrestors”. They protect against the flame running upstream and reaching either the oxygen or fuel tank, which would be bad, very bad. Supposedly my setup was not at risk for this explosive condition, but I decided I wanted the safety feature anyway.

And in that same sense of caution, I installed fire extinguishers at several locations in the shop.

Do I finally have the right stuff?

Since I once blew myself up and almost burned my dad’s garage down I suggest:

Make sure someone else is home

Have an escape plan

Wear a face shield and wool turtleneck and gloves

Consider shaving your entire head

Consider an ejector seat

This is why I sometimes visit Habitat for Humanity or other construction recycling centers. You might have found a “junked” hood from someone refurbished kitchen project cheaply!

Sent from Yahoo Mail for iPad

I wish I could have found a recycled vent hood. I checked with our local construction surplus center but no luck. Should have checked the Habitat outlet (I donate, but didn’t think of it; oh well, next time)