My idea of creating a vacuum was terribly simplistic. Just run a pump until you reach your desired vacuum, right?. Well… I learned that there is much more to it.

First, there are different degrees of vacuum, categorized by how difficult it is to attain them. The easiest can be obtained by a mechanical pump, a piston, or equivalent, pushing air molecules from the chamber to the outside, essentially a reverse bicycle pump. It is possible to remove 99.9% of the air molecules and a few more, but that still leaves too many for the cool vacuum electron effects like neon signs, nixie tubes, and for audiophiles, amplifier tubes.

The mechanical vacuum pumps can’t reach those levels; more exotic pumps are needed, but they can get close to where radiometers operate, which is my interest. So following the advice of expert friends, I acquired a pump that, in principle, could reach the level of vacuum I needed: 50 microns (a micron of mercury air pressure is 1/760 thousandth, call it a millionth, of standard atmosphere). The pump model I bought is commonly used by the HVAC industry, where air conditioning units need to be evacuated before charging them with refrigeration working fluids (Freon, etc.). They can reach the 50 micron vacuum level internally, but if you connect it to a real world vacuum chamber, there is a myriad of “leaks” that will prevent getting there.

I found this out by trial and error. I found that the hoses, fittings, and gauges from the HVAC world were not cheap, but there is a market to keep them reasonably affordable to the industry’s practitioners. Vacuum-rated hoses, gauges, valves, and fittings (the connectors between vacuum elements that minimize leaks), are hard to make. And they all seem to have their own connection systems. I learned about “flare” fittings, “nominal pipe thread” and tapered thread, acme threads, o-rings, and a bunch of other methods for connecting things and trying not to leak air molecules.

When I couldn’t reach my desired vacuum, I examined every connection for leaks, and every hose for “outgassing”: the emission of molecules from a material into the vacuum. If you can smell the odor of an object, it is outgassing. The rubber or silicone hoses were good enough for HVAC work, but seemed to emit a low level vapor that prevented a deeper vacuum.

The fittings, usually brass, were also suspect. Flare fittings are designed to have two conical metal sections compressed together tight enough so that molecules cannot squeeze through. Or sometimes a metal to rubber seal is used.

The hoses and fittings come in different diameters for different pipes. I ended up trying nearly all of them in an attempt to make a vacuum system that could reach my 50 micron target. As a result, I have a rather large parts bin of fittings, couplers, unions, and adapters, most of which were purchased while not fully understanding the different thread types. This is the learning curve cost. I could probably have taken a course in vacuum systems and learned the same things. But then I wouldn’t have my collection of useless fittings.

The most significant obstacle ended up being the hose between the pump and my bell jar vacuum chamber. I started out with a ¼” diameter, 8-foot long hose, commonly used by HVAC technicians. I then learned that long thin hoses don’t work well for the vacuum I was trying to reach, so I acquired a shorter, larger, 4-foot hose. This required replacing all of the fittings to accommodate the larger size. But this failed to reach my target vacuum as well, so I tried an even shorter hose, but the pressure still could not get below 200 microns.

I began to suspect that the hoses used for refrigeration work might be the problem, but how? After all, HVAC technicians are very successful at getting our cars and homes air-conditioned for our comfort. But their hoses are made from various combinations of rubber and elastomers, silicone and cross-linked hydrocarbons, all of which have some level of evaporation and outgassing, a vapor pressure, emitting molecules into the vacuum. Perhaps this was the limitation.

“High vacuum” systems, those used to reach levels where thermionic emissions are possible, where cathode rays and plasmas, x-rays, and quantum effects occur, require much different equipment. There are no rubber hoses or plastic ball valves. It is all metal and glass; items that don’t outgas. Even the “hoses” are metal, their seals don’t use rubber o-rings– they are copper gaskets wedged against stainless steel knife edges by specially levered clamping nuts. The high vacuum regime is a whole new world that involves gaining entry to a much more exclusive and expensive club whose members have earned their place by virtue of making all the mistakes I have, and more. There is an extensive lore of knowledge held by these practitioners.

I was trying to avoid the high expenses of high vacuum. Evidently, HVAC vacuums are quite modest and can be managed with hoses and fittings with rubber gaskets. Thermionic vacuum tubes and plasmas on the other hand, need something much more. Unfortunately, the vacuum I needed was in between these two regimes. Refrigeration technology was almost, but not quite adequate, and plasma physics technology was overkill.

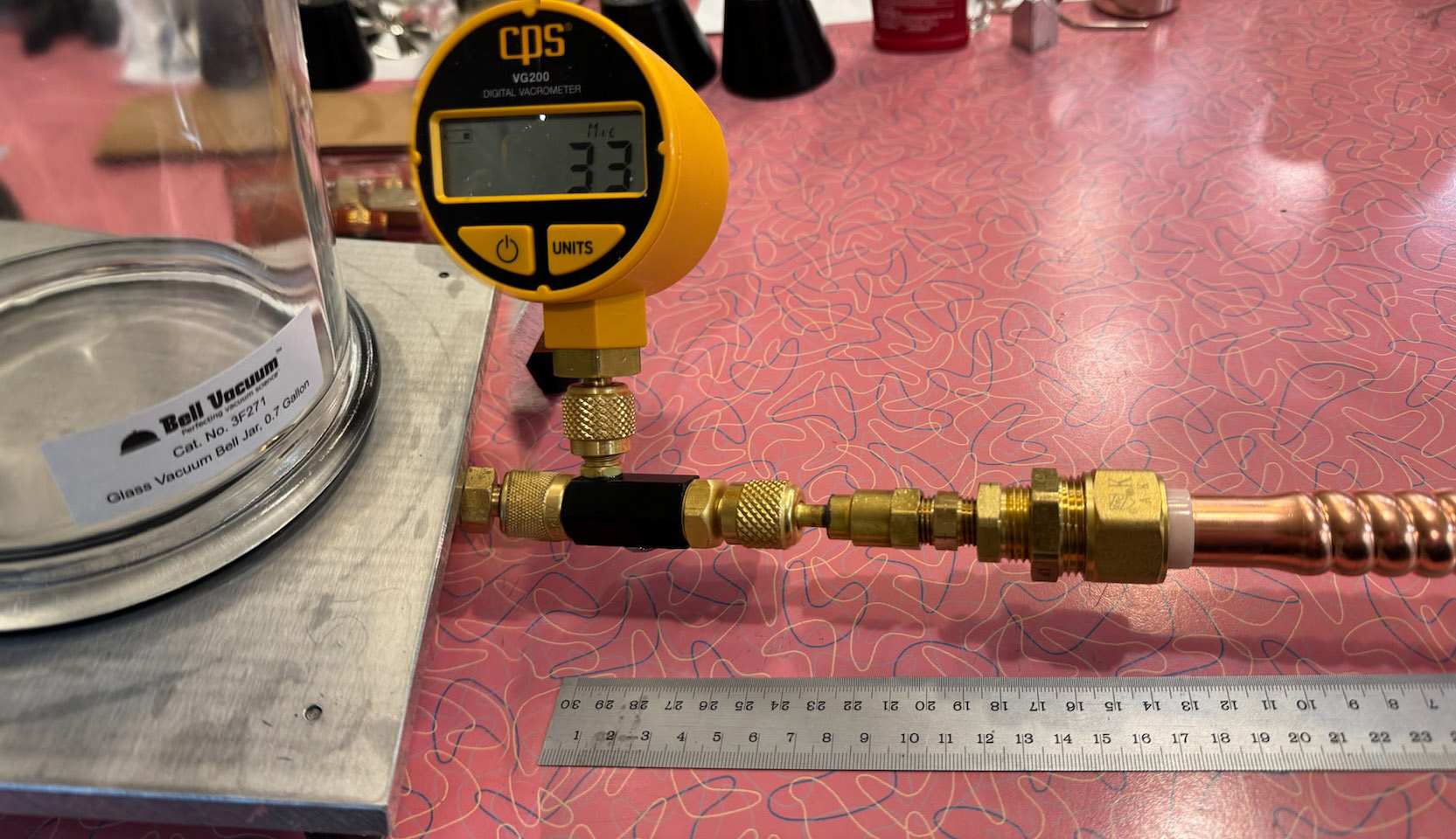

I continued my efforts to create a deep enough vacuum with parts I could find at Amazon or local home supply stores. I didn’t want to escalate to specialty metal hoses and clamps, but I discovered that metal hoses are available in the plumbing department of the home store. I found a short section of corrugated copper pipe used for hooking up water heaters. It could be bent into a desired shape, and had ¾” pipe fitting ends. These were too large for the rest of my vacuum system, but the store also had adapters to go to ½, then ¼”. It was a little clunky, but when sealed with Loctite, the fittings became vacuum tight and I was finally able to reach my 50 micron target pressure!

Now that I have accomplished this milestone, I am ready to begin my radiometer experiments. All it took was weeks of trial and error, and an accumulation of all the wrong stuff.

on the subject of glass chambers, I once exploded a thermopane window. It was quite dramatic but no animals were hurt.