When we consider the impact of computer graphics we usually think of Hollywood motion picture special-effects, or beautifully crafted images and commercials from high-end marketing firms, which both seem like products of the east and west coasts. We don’t think of midwestern artists or public university departments as being part of that world. Yet this is exactly where much of the pioneering work in computer graphics was done and its commercialization was born.

An artist who was one of those pioneers lives in Columbus Ohio. Charles Csuri started using computers in his art in 1964, and among his many world-changing achievements as an Ohio State University professor, founded the Computer Graphics Research Group, the Advanced Computing Center for Art and Design, and co-founded Cranston-Csuri Productions, one of the first companies to make computer animations. Their work was ubiquitous in 1980s television commercials.

He also founded the Ohio Supercomputer Graphics Project, which is where the influences of this artist indirectly impacted my own endeavors in the field of computer graphics.

Today we enjoy hi-definition “HD” images everywhere with millions and millions of pixels making up our displays and cameras. But in 1980 “high resolution” meant a few hundred pixels across and down: 640 x 480 was the standard. The company I worked for, Management Graphics Inc, MGI, was pushing this limit. We developed equipment that could record onto film computer-generated images that were 2048 and even 4096 pixels across!

Our product, the Solitaire Image Recorder (SIR), became quite successful. It was especially useful for making 35mm slides, a now obsolete way of visually augmenting a presentation.

Because of its ability to make such high resolution images, the SIR found its way into other applications beyond presentation slides. One of our customers was the Ohio Supercomputer Center whose Graphics Project department needed a way to record their work. They pushed the technology further, onto larger film formats: four by five inches, more than 10X the area of a slide.

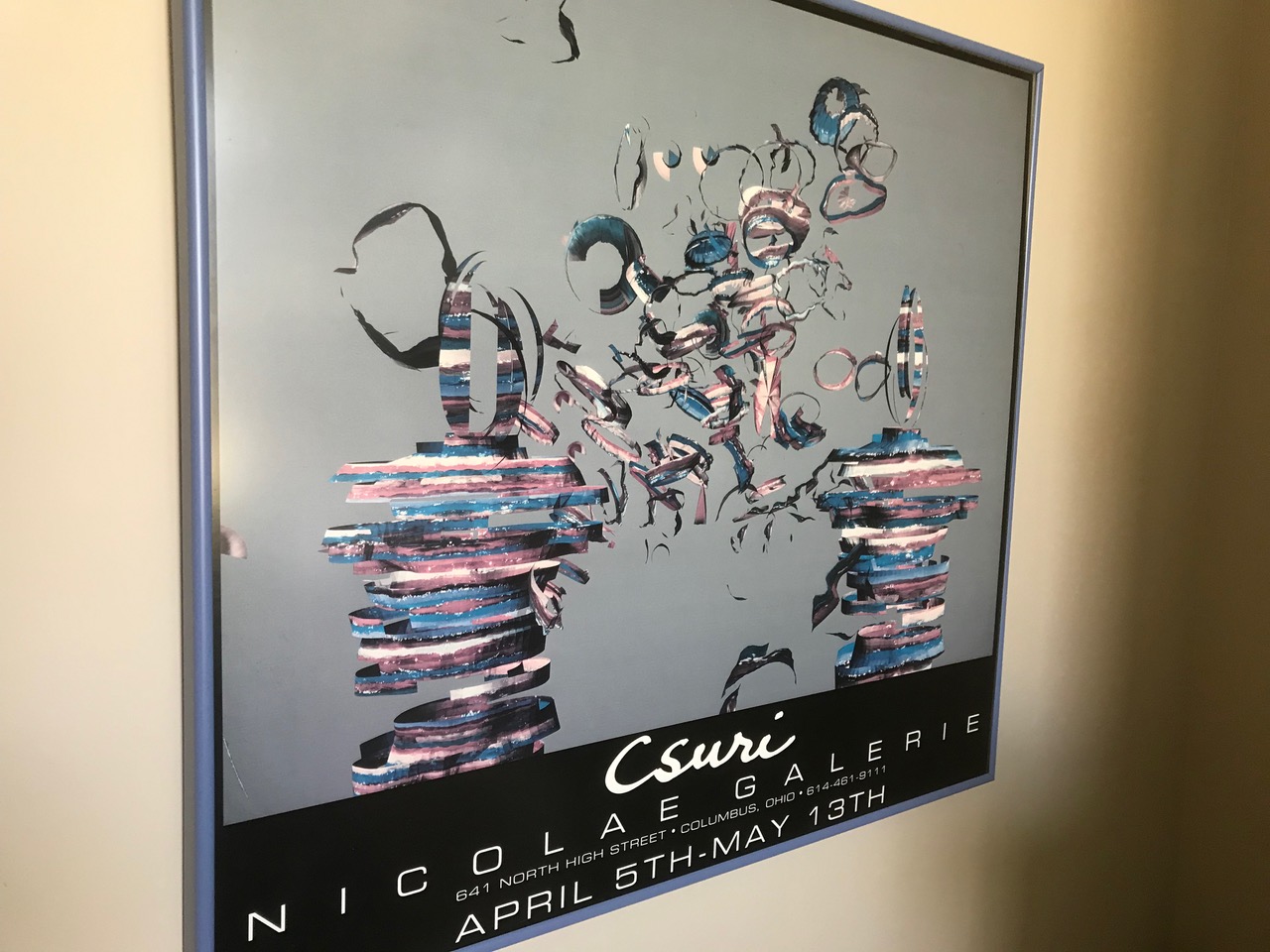

This was the department that Charles Csuri founded. One of its projects was to create an image for a poster announcing an exhibit of Csuri’s work. A recent (digital) work of his, “Gossip”, was imaged onto 4×5 Ektachrome film. This was then used to create and print the promotional poster.

During that project MGI manager Tom Peterson paid a call to follow up on this account. Here was a supercomputer center where our equipment was being used! Whatever they were doing with it, perhaps they could recommend it to other supercomputer centers. While there, he happened to notice several of the Csuri exhibit posters on display and made a request for one. Tom brought it back to the MGI office, framed it, and hung it prominently in the lobby as an example of our technology at work.

Every day I would walk past it. The artistic aspect of the work was delightful, but the technical rendering was awful. The large format film had captured the details of every pixel, exposing and amplifying any slight errors. It had recorded the subtle defects of the entire raster and when enlarged to a two-foot square poster, this resulted in a background texture that permeated the image. Others may have taken the texture as part of the artist’s intent, but I knew better.

This provided a personal motivation to improve on the technology. We were learning what was needed to eliminate the raster texture. We did experiments with pixel sizes, positioning accuracy and the influences of random noise. In the end we invented a new version of Solitaire Image Recorder, the SIR-8XP, which could expose 8096 pixels across the image and create an absolutely smooth background.

I would have liked to re-image the Csuri artwork on the new machine, but the image was not ours to use. We had other test images to demonstrate the improvements, but they just weren’t as cool.

All things must pass, and this particular field of computer graphics matured. Film as an imaging medium was replaced by digital sensors and displays, and MGI went on to work on other technologies, eventually being acquired by another digital imaging company. The framed poster was moved to a new corporate location, but there was no reason to display it, and so I salvaged it from the surplus furnishings headed for the scrap market and kept it in my office. Thirty years after Charles Csuri created the piece, unaware of its origin, I sought to find out its history.

In addition to discovering Tom Peterson’s role in acquiring it, I tracked down the gallery whose exhibit was being announced. It too was no longer around, but its principal, Nicolae Halmaghi, is still active in the creative design world. In a correspondence, he confirmed that his gallery represented Csuri, exclusively, along with only two other computer graphic artists.

It was a unique time, and the techniques were evolving rapidly. The breakthrough that made works like Gossip possible was called “texture mapping”, where an image of something, like say a picture of painted brushstrokes (which Csuri prepared), could be “wrapped around” objects in their 3D computer world and then rendered to a virtual camera view. The colors and texture of the fragmented bands in the piece are the result.

During those pioneering years researchers from many industries and institutions were learning the requirements and inventing the technology for digital imaging. The 1990s were an exciting time to be part of the world’s transition, and I’m proud of the contributions that MGI made. This poster and its story embody some of the lessons learned along the way.

NOTES

Charles A. Csuri was awarded a Distinction by the Prix Ars Electronica jury for his entry Gossip in the category Computer Graphics. The Prix Ars Electronica is an international compedium of the computer arts, Linz, Austria.

HISTORICAL SIGNIFICANCE

A function for fragmentation was used to break the figure into pieces. It has the capability to make clusters of fragments, control their range of displacement and to rotate them. The center section is the same as the figures on the sides but with a greater displacement. I made a painting of just stripes. My painting was scanned and then I mapped it onto the 3d models. The center section was shifted and rotated many times before I thought it worked in the space.

Also exhibited at: SIGGRAPH 2006: Charles A. Csuri: Beyond Boundaries (1963-present)

From https://csuriproject.osu.edu/index.php/Detail/objects/76