3.1 Follow the light, stay for the night

I thought I would have plenty of time. But I had forgotten about Highway 2. On the map it looked like any of the other roads, but U.S. 2 in Montana was different. Since it was the only way to reach Glacier Park, it had to maneuver through the surrounding mix of grasslands, river valleys and mountainous terrain. Sudden curves were sprinkled along the route to accomplish this, many of them blind to oncoming traffic. White crosses marked points where the risks had exceeded a driver’s judgment, making for a spooky drive at night, when my headlights would suddenly expose clusters of crosses at the road’s gully.

This time I was driving during daylight however, and the winding route kept my speed to a lower number than my accustomed average. I had composed another picture in my mind’s viewfinder, and I needed to get to the heart of Glacier Park before dark.

When at last I reached West Glacier, the small tourist outpost at the edge of the park, it was late in the afternoon. Highway 2 had taken its toll on me and I stopped to refuel my car and myself at a café-motel-gas station at this last point of civilization. The food was good, the huckleberry ice cream a signature treat of this part of Montana. I found out I was still a couple hours away from Logan Pass, the top of Going-To-The-Sun Highway, the not-for-the-timid route through the park.

I was stopped at intervals by road construction, but on a clear day in late afternoon, the scenery took on a magical appearance and I savored the drive. The road steepened and narrowed, taking me through tunnels, hairpin turns and cantilevered sections hanging from the side of the mountain, eventually reaching the top of the pass. The sun was low, but not yet setting on this long July day as I turned into the parking lot at the visitor center.

The Logan Pass Visitor Center is a very popular destination, and the parking lot that serves it is immense. In spite of its size, it fills up beyond capacity and not everyone gets the opportunity to explore the visitor center and the trails beyond. At this hour however, I could find a place to park, and I eagerly headed up to the log building to check in with the rangers, find out about the weather and hiking conditions, and generally just catch up as an old friend of the park. The door was locked, the sign explaining that it closed at seven. I looked at my watch. Seven.

People were drifting back towards their cars from family excursions down the boardwalk that penetrated the alpine meadows. The end of the day is tough on some, particularly young children whose enthusiasm takes them obliviously beyond their threshold of hunger or thirst or fatigue. Various dramas played out as I watched from the periphery of the parking lot.

I looked around. I was here! I was at the top of Glacier’s world. I could look down into the glacier-cut valleys but was still shadowed by the heads of mountains that stood even higher. To the west silhouettes of their profiles, to the east, peaks that glowed in gold. I had been here before, but as I now examined the site of my photographic goal, it didn’t match my mind’s image.

I had to rethink my composition, but standing at the top of one of the most beautiful places on the planet, I didn’t have to look very hard to see new possibilities. Pollack Mountain loomed to the north, Mt Clements and Mt Reynolds to the south and west. The valley to the east was bathed in the afternoon light and realizing that it wouldn’t stay this way, I headed back to my car to get a camera.

In the parking lot I found several other photographers setting up tripods and selecting their right lenses. More cars were arriving, and more photographers piled out of them. I was surprised at this. I knew that Logan Pass was popular, but I had no idea that its photographic possibilities were so widely known. Are there photographers hanging out here every afternoon waiting for sunset?

I gathered my camera with its one and only wide angle lens and installed it on a tripod. There. I could be a nature photographer now too. I tried to strike a conversation with one of the others in this apparent fraternity.

“So, what are you guys shooting?” It was kind of a stupid question, but I had to start somewhere; I’m not really familiar with modern cameras, and not confident enough to ask about their equipment.

“Pretty much everything.” I guess I deserved that.

There were various terse bits of advice and comments that exchanged between some of them. They all were setting up and shooting, everyone something different: wide mountain views, telephoto shots, close-ups of beargrass, panoramic vistas.

“Yeah, I guess it’s pretty hard to take a bad picture in this place.” I was struggling, but I got a smile out of him and he responded with a modest quip about being able to screw up even something this nice.

I went to the edge of the parking lot to take pictures of the valley while it was bathed in the afternoon beauty light, bracketing my exposures to make sure that one of them might turn out. I turned back to find the league of photographers climbing back into their cars and heading down the pass to the west. I managed to ask my contact where everyone was going.

“We’re following the light!” he called out.

I wasn’t following the light. My light was still to come, and I waited patiently for the coming sunset and twilight.

The late afternoon breeze pushed cumulus clouds through the pass, some of them containing excess water. The rain drained from them in dark smears as they proceeded down the valley, to eventually disappear entirely. The mist that was left behind refracted the low angle sunlight into a double rainbow. From my vantage point, the rainbow was complete, its ends striking each side of the valley making a perfect arch.

I was amazed at this. Catching sight of even a partial rainbow is a rare treat for me, but to see one this large was a life treasure! While many people in my position would stand and savor the view, my reaction was to take its picture.

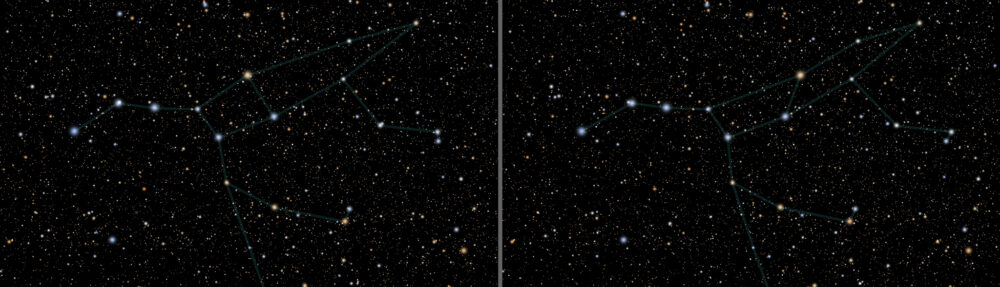

It exceeded a normal viewfinder (a rainbow is 84 degrees across!) and the widest-angle lens I possessed just barely fit it in the frame. I did my best to center and arrange the shot during the short life of the ephemeral arch. The picture captures the abrupt eerie change in lighting from inside to outside the rainbow. I was elated to have been at the right place at the right time.

The miracle of optics that makes a rainbow is well-known, but not widely-known. Descartes explained it by tracing rays through raindrops with geometry. It has been explained with principles of quantum mechanics (ref: Scientific American 1976), but it really doesn’t require advanced mathematics to understand and appreciate. I like to think about how the light coming from the sun behind me encounters raindrops: every optically significant surface reflects and refracts the light. In the case of clear spheres of water, there is a front surface and a back surface where the speed of light changes as it crosses between air and water and then back into air.

Can this be? Didn’t Einstein tell us that the speed of light is constant, and maximum under all conditions? This is true in a vacuum (if there is such a thing), but when light encounters a material, it is diverted and detained by clouds of electrons around the atoms that make that substance. The ratio of the speed of light in a vacuum to the speed through its atomic hurdles, is the material’s index of refraction.

And whenever light encounters a change of index along its path, some is reflected back. Some is reflected from the front of the raindrop, and some is reflected from the back.

In the shower curtain of raindrops from the cloudburst, a little light is reflected from the fronts of each drop. Most of the light continues into the drop and a little reflects off the backs of each. Some of the light bounces twice inside before coming out. Of this twice-reflected light, most of it comes out of the drop at a very specific angle, one that is aimed right at me when I look 42 degrees from my own shadow. Some of the light is reflected back to me at smaller angles, but none reflects back at greater. Within this magic angle the backsurface-reflections lighten the scene. Outside it, nothing, just the view of the sky, obscured by the rain in front of it. So I see a circle of illumination 84 degrees in diameter, distinctly brighter than everywhere outside it, a backscattered reflection of the sun centered on my shadow.

At the circle’s edge, another effect shows. The speed of light is not the same for all colors. In water as in most substances, red is slightly faster than blue. The fast red light bends less than the slow blue resulting in its angle being slightly larger, with the other colors falling in between. By the time the light bounces off the back wall and comes back, there is a difference of 2 degrees, enough to splay the colors out into the rainbow boundary. It is breathtaking; it takes our attention so fully that we don’t notice the huge circle of reflected sunlight it contains.

I was essentially alone in the parking lot to witness and capture this event. I thought about the gang of photographers that had been here moments earlier. The sun had now lowered even further, changing the light to that impossible mix of cold blue and warm red. The distinctive shape of Going-To-The-Sun Mountain was catching the last direct rays, the shadow of its neighbor squeezing the orange band of light to its summit.

As I recorded this scene, I heard cars entering from the road. The photographers had returned, evidently following this new phase of sunlight. I asked if they had seen the tremendous rainbow. Yes, yes, they explained with frustration, but they were on the road and couldn’t shoot it. I knew what they meant. Going-To-The-Sun Highway is a remarkable engineering achievement, taking its travelers to places normally impossible to reach by vehicle. The price paid is the absence of shoulders, there is no place to pull over and stop other than the emergency turnouts sometimes found on the inside of the curves, where the exposure was less and so too the view.

Once again there was a flurry of shutters snapping as they captured the dying light on the mountains. I discovered that this assembly of photographers did not spontaneously happen every evening, it was a class that was being taught in this photogenic outdoor classroom. As they once again packed up and headed out, I waved to their caravan. I didn’t have to follow the light. I would stay right there and wait for the night.

What a great experience! Thanks for a beautiful read.

Laurie

Pingback: 3.2 Going-To-The-Sun at Night | Thor's Life-Notes