8.1 Lions, (no tigers), and Bears

On the map Yellowstone, our country’s first national park, is immediately north of Grand Teton National Park, sharing a common border segment. So it is an easy mistake to think that it is but a short drive to go “next door” to Yellowstone from where I was in Jackson, just outside of the Tetons.

In fact, it is a full day’s project, at least the way I travel, compelled to stop at large vistas, beautiful waterways, and intriguing natural phenomena like mud pots and fumaroles, not to mention the traffic stoppages from encounters with elk and bison. And such hazards to rapid travel are everywhere in these parks.

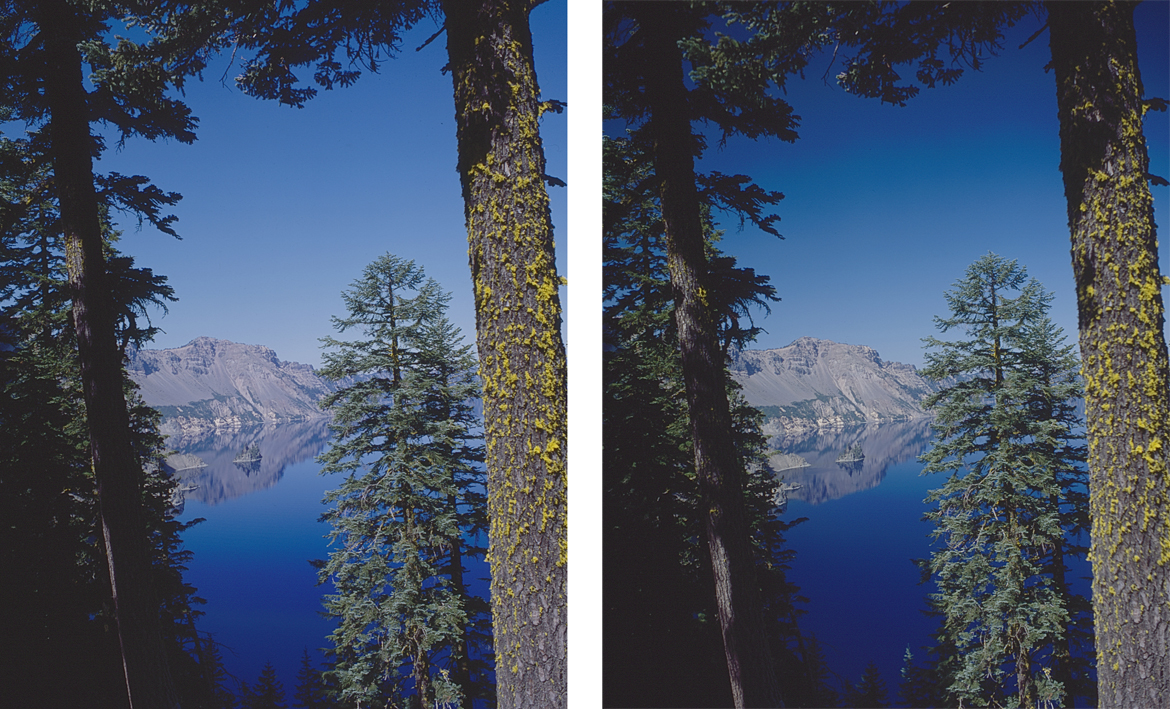

I thought about the pictures I might be able to take in Yellowstone. Among them was a nighttime shot of a geyser, its plume of water against a backdrop of stars. It occurred to me that I had carefully arranged to be here when the dark skies would not be intruded upon by the interfering light of the moon. Yet the subject I had in mind, the momentary appearance of an airborne column of water would be un-illuminated. No matter how “white” the steam and water might be, with no light other than starlight, it would be invisible to the film in my camera. Perhaps I would not be able to realize the view from my mind’s eye. Well maybe I could get some nice compositions with trees and mountains, or do some more deep sky photography, easier on a moonless night.

Continue reading