It is a concept that was introduced to me by my colleague Phil, who while recalling a dinner that we both participated in, described it as the best he had ever had. This struck me as one of those hyperbolic statements one sometimes makes in the competitive company of peers, but after contemplating his superlatives for a moment, realized it was true, and then adopted that same experience as my own best meal of a lifetime.

Continue readingCopenhagen Solstice Celebration

After checking in to our extremely compact room in Copenhagen (“you’ll find a towel, blanket and pillow for the second person in a drawer under the bed”), we decided to find a local establishment for dinner. The modern phone is an amazing tool for this as it allows you to locate restaurants within walking range, and even get a sense of their menu and pricing and how others have reviewed them.

We identified a candidate and walked the few blocks through the new winter night to find it. The European style bistro seemed just right for the occasion, so we entered and immediately found ourselves inside the coat check room. We weren’t sure we wanted to surrender our coats; it might be cold or drafty in there, but there was no option. All coats were checked; we were told that there simply wasn’t enough room inside.

Continue reading2.5 Exodus

The last night on the mountain provided the best and most prolonged views of the night sky. The clouds were gone, but the dew conditions were awful.

Continue reading2.4 Dinner and a Moonset

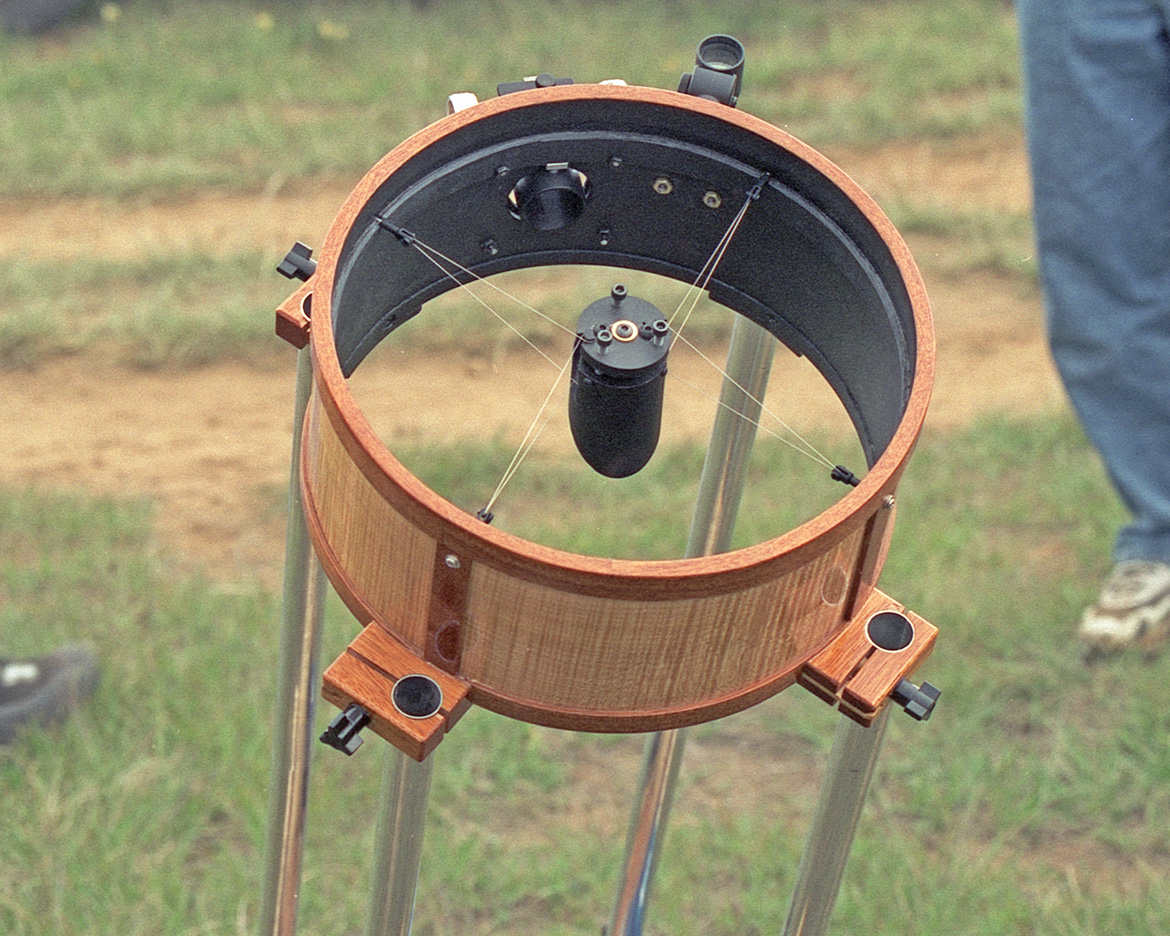

The next day’s weather was a repeat of the previous: partly cloudy, occasionally overcast, threat of rain, but then open periods of bright sun. Alongside the coffee vendors, protective canopies were set up for astronomy-related businesses and causes. Artists, photographers, telescope and accessory retailers, social and political organizations: all had the equivalent of a wilderness storefront along “vendor row”.

Continue reading2.3 Rainy Days, Espresso Nights

Most attendees had given up and gone to bed with the cloud cover at midnight. A few of us accidentally enjoyed its clearing after 2:00. We took in views of galaxies, nebulas and star clusters until the near-dawn when Saturn, and then Jupiter and Venus appeared. This was the intoxicating finale of the evening, and with the brightening sky, I staggered to my tent sometime after 4:00.

Continue reading2.2 Flat Tires, Cloudy Skies

I started lugging stuff out of my car and was struggling with my oversized tent when I met my neighbor to the east, Barry, a friendly bearded fellow who reminded me of a mild-mannered graduate student. In reality he was a programmer, but his interests fell strongly in the areas of ham radio and astronomy. He was modest about his beginner status in astronomy, but he had attended prior years of TMSP and enjoyed them immensely, hence his return this year.

Barry felt responsible for letting me know that the rear tire on my car was flat. I was surprised at this news, since I had just arrived and had not experienced any sort of tire problems on my way up the mountain, but there it was. It wasn’t just low on air– it was dead flat! Had I been driving on a rubber-covered rim all the way up that road? I suppose it’s possible, but let’s instead think that it must have happened as I maneuvered into the field. A sharp rock maybe?

Continue readingTable Mountain Star Party

2.1 The Approach

I had embarked on this “Nightscape Odyssey” to search out dark sky locations in the western U.S. and to hone my astrophoto skills. Although the Table Mountain Star Party (TMSP) in Washington’s Cascade Mountains was a long way from Minnesota, I had selected it as a fitting launch point for my ambitious summer plan.

The “star party” is an interesting concept, especially to those who are not close to amateur astronomy circles. For them it creates an amusing image of revelers eating and drinking outside, occasionally looking up at the sky, pointing to various stars and having a good laugh over them.

Continue reading1.5 When Art Speaks, Listen

It wasn’t long before the clear nights of photographic activity and subsequent days of driving took their toll. I camped in the remote Sage Creek area of Badlands National Park, where the campground was an oasis in the middle of those badlands, an oasis with no water and no open fires allowed.

The sky was dark and clear, but I was exhausted. I made a feeble attempt to ready my equipment for what promised to be a beautiful evening but decided to nap instead. As I “rested my eyes”, I could hear a neighboring camper who, with more energy and an eager audience, had set up a telescope and was conducting a tour of the night sky. Someday I will return to this unusual and remote site; maybe then that night sky guide will be me…

Continue reading1.4 When Sabbaticals Collide

I returned to the campground as the sky lost its deep darkness to the dawn. I was tired now and falling asleep was an easy matter. Staying asleep was not. Campgrounds come to life at an early hour and become noisy collections of waking families preparing for a new day. The commotion subsided when most campers had driven off to their destinations. The midmorning sun, radiating through a cloudless sky, heated up my tent. Even after moving the tent into the shade I found it difficult to sleep. By 10:00 I gave up and decided that I might as well start traversing some more of the miles toward my appointment in Washington.

Heading west on blue highway 14, I share the road with rural traffic and the occasional bicyclist. I enjoy seeing the bicyclists; they ignite the memory of an earlier epoch in my life when I would bicycle for weeks through beautiful countryside, carrying everything, and camping along the way. Bicycling is just the right speed to experience the land. A car travels too fast, there is not enough time to truly let in the details of the terrain. Walking is too slow, the details become stale before you reach the next vista. But a bicycle brings you close, living and breathing the environment you travel through, giving you options to linger or to move on.

Continue reading1.3 Crossing the Prairie

Even as one exits daily life, its anxieties drag along. I headed west on highway 12, a route that could take me to Montana and beyond. The interval between rural Minnesota towns was a consistent five miles, a day’s round trip in the days of horse-driven vehicles. Although I had no need or desire to stop, I found these distances between oases of civilization annoying–my progress seemed so slow. As I crossed into South Dakota however, and the distances started getting longer, I found my tempo slowing to match. The rhythm of the car on the pavement was beginning to seem more natural. I had no appointments or obligations, other than my desire to reach Washington for the Table Mountain Star Party. And even that was not an obligation, I could change my plans at will!

Go west! Ride the road and make my plans on the run. I could go as far as I wanted, stop where I felt like it, and make my way, my way. And like the title of the book by William Least Heat-Moon, I was traveling the blue highways. Except by the conventions of today’s maps, the lesser traveled roads are marked in red, not blue. The two-lane roads serviced the rural business, farms and ranches, and the segments between the small-town hives of activities became longer as the hives themselves became smaller.

Continue reading