There is a more general problem related to the “what to do with old lab notebooks” that some of us face. It is what to do with our shoeboxes of photos (virtual digital shoeboxes and real ones). And written correspondence. Love letters. Birthday cards and holiday cards that caught our attention enough that we saved them. The trophies, actual physical trophies, or the certificates of commendation for a job well done. Birth and death announcements. Souvenirs of our travels, the mementos of the high points of our lives.

All of them carry great meaning to us, invoking a romantic haze of fond memories from those times and places, for those people and events. Yet those memories are internal to us; they are not shared, even with the persons we may have shared the moment with—at least not exactly. Each of them has his or her own version of those scenes. And they are not shared in the same way with our children, and certainly not their children. Our lives are an abstraction to them. They weren’t even around when the main story was unfolding.

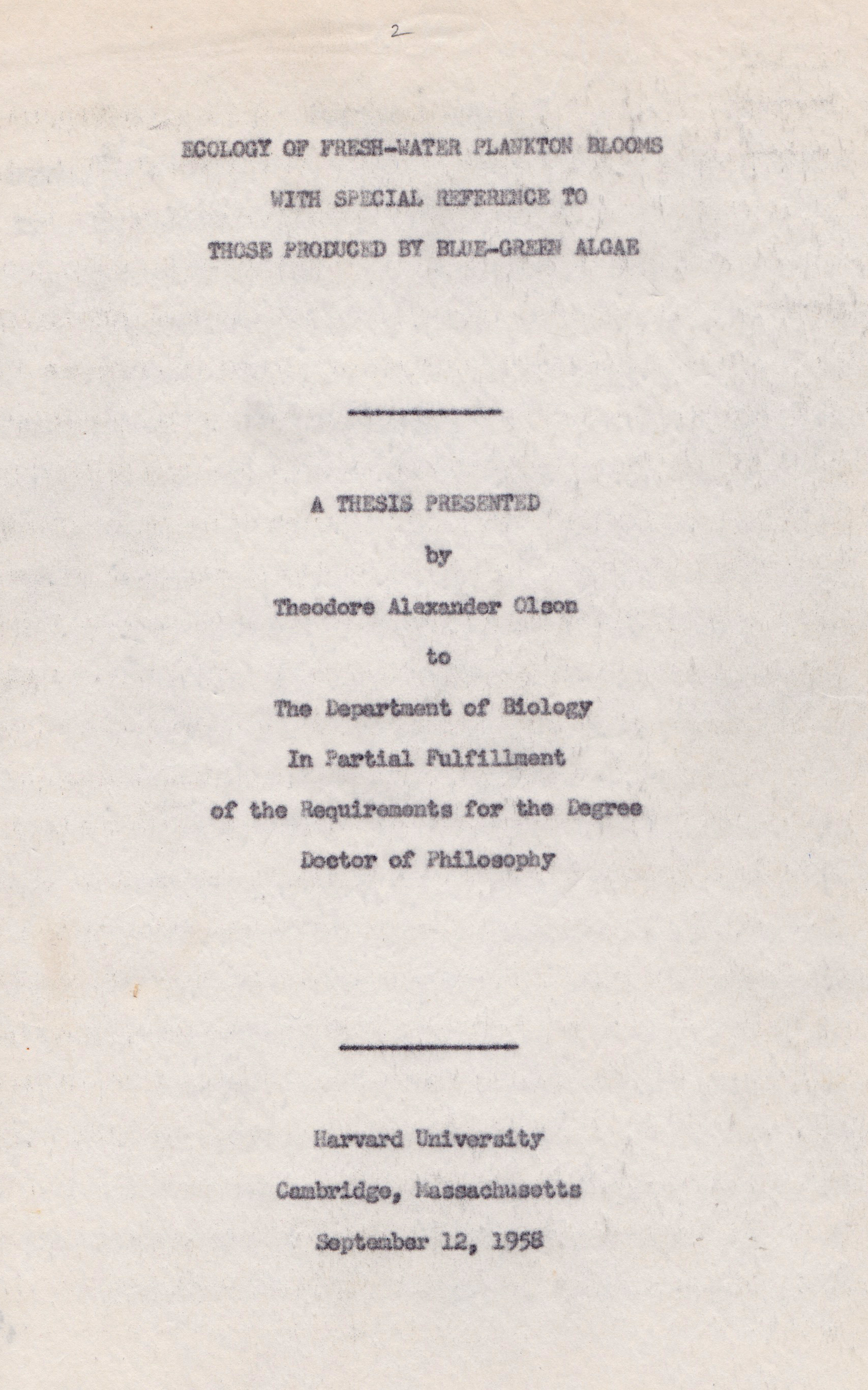

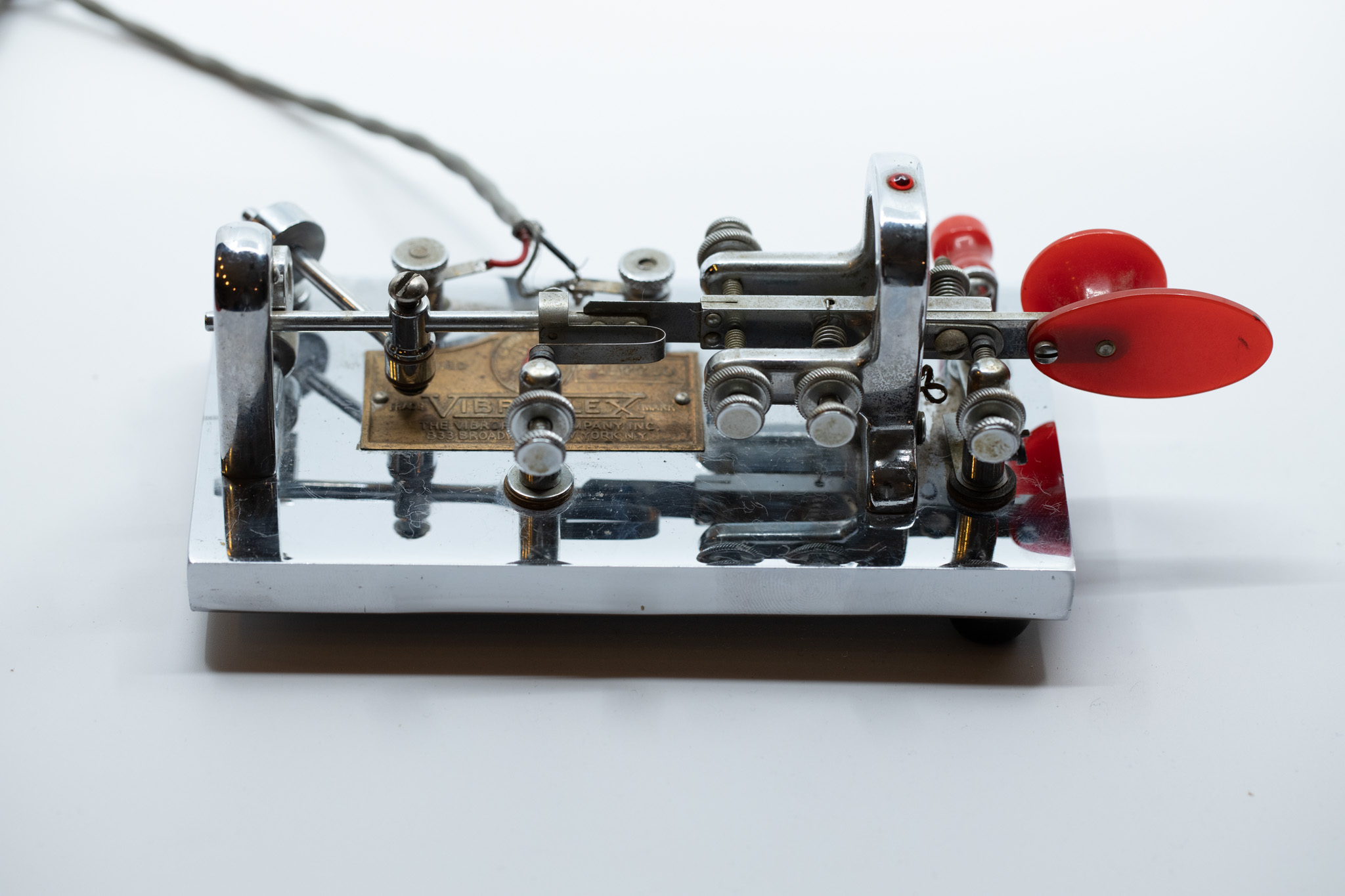

I have come to realize this in the last few years as I have processed the items left behind by my parents after their deaths. I have a high regard for my father’s technical acumen and his many projects. Some of them were to gather and archive family history, others documented his personal interests. He was always an early adopter of technology and embraced digital photography well before I did. He acquired a large collection of both film and digital pictures, organized in shoeboxes and digital folders. He worked to digitally scan historic family photos that dated back to the 19th century.

There is a treasure trove of history here, some even recent enough to overlap with my own, yet I do not find myself compelled to explore it. And therein lies the problem. If I am not inspired to carry forward the artifacts of prior generations, why would I expect subsequent generations to propagate mine?

Continue reading