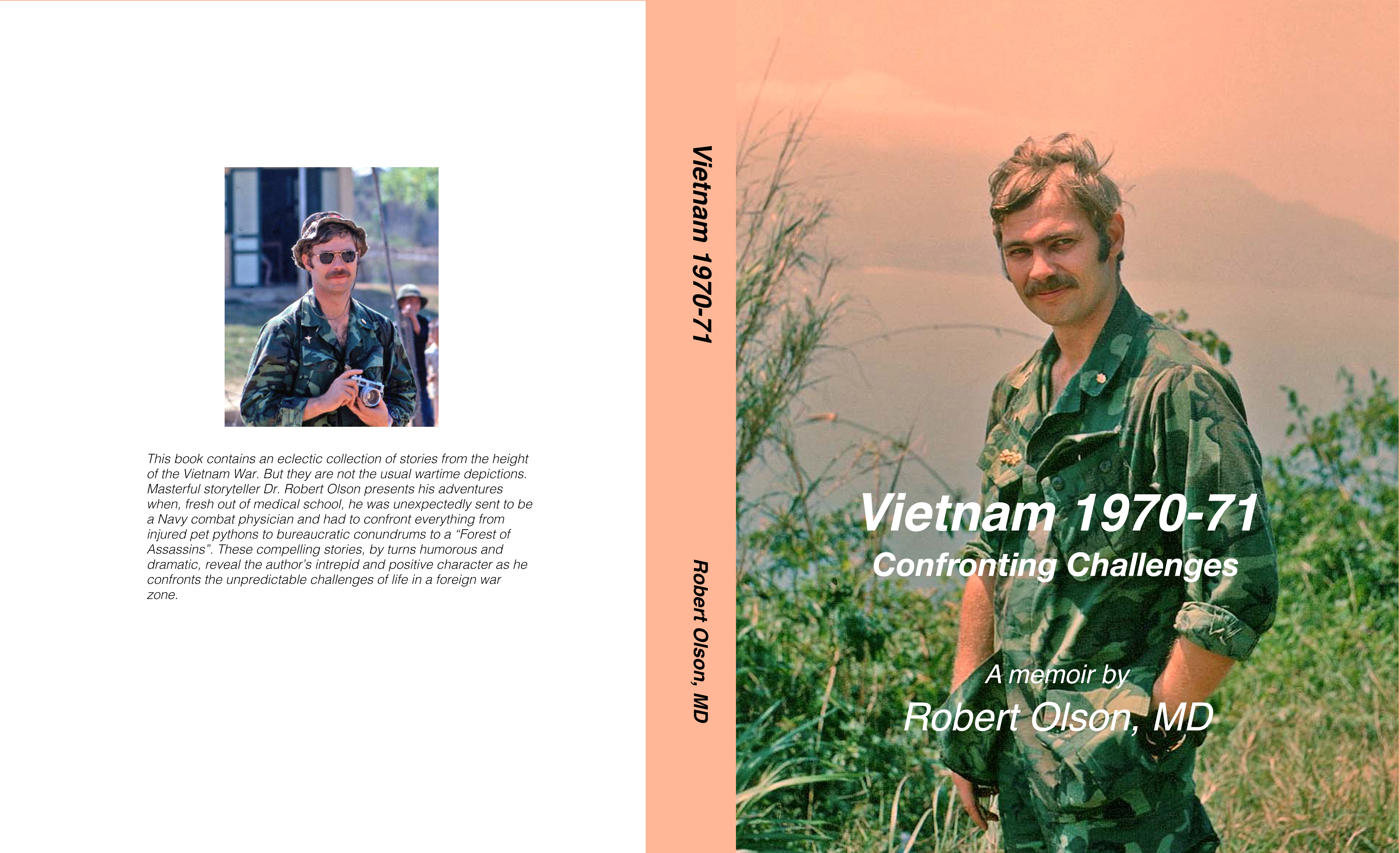

Cover art for “Vietnam 1970-71, Confronting Challenges” (click to enlarge)

I helped my uncle complete a memoir in his last weeks of fighting multiple myeloma. It is a collection of stories, told in his inimitable style, of the year he spent in Vietnam in 1970-71. My foreword for the book is below.

The book was self-published through my Blurb account for the benefit of close friends and family. There have been others that have expressed an interest in having a copy of the book. There are a few options. If you want a physical memento that you can hold and read and cherish, you can order one from its Blurb book page.

The listed price is the actual cost (there is no markup). Custom printed books are expensive, but you get a real hard-cover book! To reduce the expense slightly, Blurb makes promotions from time to time with discount coupons. You can Google “Blurb coupons” to find them. I once encountered and used a 40% coupon.

If you do not need the artifact of a physical book, the content is available here in a (50MB) PDF file for free. Download and enjoy it. Maybe you will decide you need it in a form not requiring a machine to read. If so, go ahead and order the book.

Here is my introduction to Bob’s memoir:

Foreword

The author of this volume is Dr. Robert Olson, whom I know as my Uncle Bob. Over the years I heard him tell stories of when, fresh out of medical school, he served as a Navy doctor in Vietnam. Now, over the last 12 years, he has worked at putting words to paper to capture the remarkable experiences of that life-changing year, and he has collected photographs of that time, taken by himself and others.

It has been my privilege and honor to assist Uncle Bob in assembling this book. While he is a master storyteller, he is not a master of the modern tools of writers. But as you will see as a recurring theme in so many of the stories that follow, he took on that challenge in his signature manner—head on, picking up what he needed, as he needed it, to accomplish the task. Microsoft Word, hardly an intuitive editing tool, was Bob’s choice to render his material and turn it into text.

Which he did.

The modern tools of writing allow for easy revisions. And he made many of them, carefully crafting each story for impact and detail, augmenting them with photographs to illustrate the locations, people and world context of the times.

When it became apparent that he would not be able to take on the final task of assembling the stories and photographs into a full book and actually publishing it, I offered to help. I obtained his large “working folder” of the many files he had created over the course of a decade. Despite failing strength and plummeting hemoglobin levels, he confirmed the titles of his stories, eventually to become chapters in the book, which I then used to locate their most recent versions.

As I performed my new role as copy editor and typesetter, I learned the backstories and more complete details of these events, many of which I had never heard before, and I was struck by a recurring theme. It is hard to express succinctly, but it has to do with how we respond to events that are not under our control, not what we expect, not what we want, outside our experience or skill, and sometimes even frightening.

This sort of event happens to all of us: life is unpredictable, and stuff happens. In these stories, we see a response that does not shy away, but rather, meets the challenge head-on. It is more than just “making lemonade from lemons”; it goes beyond “rolling with the punches”. It is a full embrace of these unexpected and undesired events; an acceptance and a firm resolve to do the best you can in a difficult situation.

And in the end, two results obtain: the outcomes are better, and you are better.

I am struck, but not surprised, that Bob considers these difficult, challenging moments to be among the highlights of his life. I hope that after reading this book, you will understand why.

Thor Olson

September 2022