Unlike our previous visit which was part of an extended road trip, we planned a more streamlined experience this time: flying to Las Vegas, renting an SUV, and “car camping”, literally, in the desert. We brought the essentials: sleeping bags and pads, collapsing camp chairs, a minimalist stove for heating water and canned or dried food, and of course, our French press coffee maker. The idea was to shift our gear around at night to make room in the back of the car so we could sleep there. All we needed was a place to pull off the road far enough to qualify for “dispersed camping”, and we could roam freely in the back country of Death Valley, hiking and exploring by day and capturing pictures of the sky at night. It was a romanticized image which we didn’t quite achieve.

We started out well, acquiring food and fuel in the suburbs of Las Vegas, then spending a night in the small town of Beatty, just outside the park. The weather forecast was for winter storms however. California had recently been hit by “atmospheric river” effects, dumping rain and snow over vast areas, including the Sierras and this high Nevada town. The skies shifted from desert-clear and sunny, to overcast with threats of precipitation, and it looked to remain so for most of the week.

This did not dampen our enthusiasm; A “winter storm” in Nevada just doesn’t carry the same threat as what we had just left behind in Minnesota. The temperatures might approach freezing? Oh no! What will we ever do?

Well, we sauntered over to the breakfast diner and planned our day.

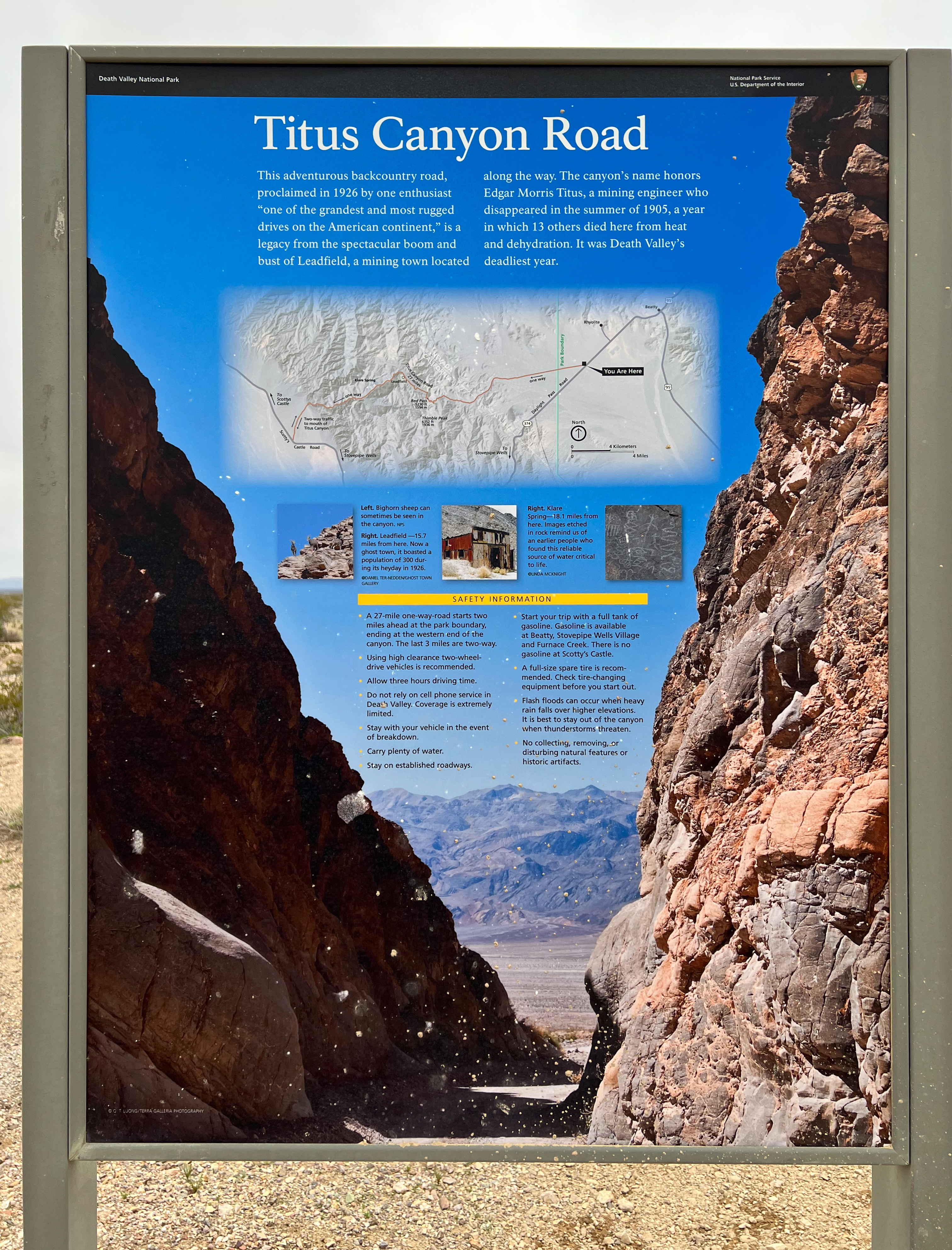

We had hoped to take the famous Titus Canyon road into the park, but it was closed, not just for winter, but because torrential flooding the previous summer had damaged it. It was already one-way only, and restricted to properly equipped vehicles (length-limited and no trailers!), but now it was impassable for all.

But the highway leading from Beatty, at 4000 feet, to the sea-level floor of Death Valley provides similar beautiful views, without the harrowing hairpins. We made our way to Stovepipe Wells Village, an oasis of services including a first-come first-served campground. We wanted to get there early, not knowing what the demand for campsites would be.

It was not what we had imagined in that romanticized view of desert camping. Instead, we encountered a vast dusty RV parking lot, the outer edges of which had been allocated to “tent camping”. The campground was enormous, but clearly catering to the RV behemoths needing electrical hookups. Coming from a state where campsites are spaced to provide privacy among the pine trees in a boreal wilderness, this was really rather unappealing to us.

Poldi was reluctant, but I convinced her that we should claim a site (there were plenty of RV slots, but a limited number for tents), and if we found something better later, well, we could afford the seven-dollar loss for the option.

We claimed our site and then headed out to somewhere more interesting—Wildrose Canyon and the Charcoal Kilns, a climb up a paved road that became a gravel road, and then a rugged gravel road, eventually ending where the snowplows and road graders can’t reach. It happens to be at a strange set of brick beehives, large furnaces, “kilns” for the purposes of converting logs to charcoal. It is hard to imagine now, but the economics of the times motivated the creation of these structures to process the meager pinyon trees here into charcoal that could be sent to smelters concentrating the metal ores being mined nearby.

It didn’t last long then, and neither did we now. We examined the kilns in the snow that was falling, then backtracked to a road that took us over the Panamint Mountains to the next basin, eventually to the trailhead that we intended to hike.

The weather had improved, and we made our way up a route where the moisture on the ground gradually became a trickle of water, and then a regular flow that defined a clear pathway up. A water pipe was occasionally visible along the side of the steepening canyon along our route, eventually ending at a pool just below a waterfall, Darwin Falls. I suspect the pipe delivered its valuable contents to some thirsty destination.

We returned from the hike, tired and ready to be refreshed at nearby Panamint Springs Resort, an oasis that offered lunch and a cold beer. I had been here before, in 2005, during a peak desert bloom, and it brought back memories of another great experience in Death Valley. It had not changed much in nearly twenty years.

In this part of the country, everything is distant. It was a long but spectacular drive back to Stovepipe Wells; our campsite was a bit of a letdown to an otherwise wonderful day.

Yet, as we prepared for our first evening in the desert, we started to appreciate our corner of the vast campground. We set up our camp chairs, aimed them away from the parking lot toward the open terrain of sand and mesquite bushes, and enjoyed a glass of wine with a bowl of Mike’s Mighty Good Ramen. Life is good, even in a place named Death Valley.

Pingback: Death Valley Days, and Nights | Thor's Life-Notes

Pingback: Tecopa Springs | Thor's Life-Notes