Most people now acknowledge that the climate has changed, even if they don’t agree on the reasons for it. Some of us are old enough to have seen the change firsthand.

As a teenager in 1970, I went on a hike with my family in Glacier National Park, a six-mile and 2000 foot climb to Grinnell Glacier. It was a thrilling experience to be hiking in the mountains, and then to actually walk out onto a real glacier! Both mountains and glaciers were things I had read about, but never personally experienced.

It was a ranger-led hike, and I learned a lot from the ranger’s descriptions of the geology, the plant and animal life, and the nature of glaciers, for which this park was named. I remember him telling us that the glaciers were shrinking. Nobody knew why, but it was possible that in a century they would all be gone. The park would still be called “Glacier”, but for the characteristic and beautiful glacier-cut valleys, not for the presence of glaciers themselves.

I have since had the opportunity to visit a few other glaciers including Sperry Glacier, also in Glacier Park, and the Athabasca Glacier, part of the Columbia Ice Fields of Banff National Park in Alberta Canada. Of course, whenever I have made these excursions, I have taken pictures, which have remained sequestered away in old photo albums or shoeboxes.

On my recent trip to Banff I was again treated to the spectacular views of mountains and glaciers, but something was different; there were vastly more people, and the icefields were smaller than I remembered. Certainly they were farther away than I recalled. I have a memory of being able to walk up to the side of Athabasca Glacier from a roadside parking area and place my hand on the blue wall of ice. The glacier was now a mile back from the road, unreachable except by specialized tourist excursion busses.

Since I was on a tour that included it, I transferred to the bus that could transport us out onto the glacier itself. We were taken to a roped-off section, safe for ice busses, safe for tourists, much like the floating ropes marking the swimming area at a beach. It was different from my previous glacier hikes—the ice surface was too clean! Rather than the black mix of sand, gravel, rock and ice that one finds in May on the accumulated pile of winter-plowed snow at the corner of a parking lot, this was more like the slush one finds on a popular ski run in spring. Too many tourists had trekked this area.

Still, it was a novel experience in a spectacular setting. I contemplated the hundreds of feet of ice beneath me, and its slow flow down the mountain to the receding front edge, which deposits the rock debris it has carried for centuries, to its terminal moraine.

The tour took us to other stops, one of which I would never have visited, had it not been part of the itinerary: a glass sidewalk over the Athabasca river valley. I consider it to be anathema to the goal of protecting parkland wilderness, but it did have one redeeming feature: along the walk to the steel and glass protuberance there were informational displays describing the landscape and geology and history. One of them showed three pictures of the receding glacier over the last century. It caused me to wonder how my photos, from 46 years ago, would fit in the sequence.

When I returned from that trip, I was able to locate the previous pictures I had taken of Athabasca Glacier. (Finding them provided an impetus to start an ambitious project: scanning my old film images. I have thousands, and it will be daunting, but this seemed like a good place to start). My viewpoint of the glacier was lower than the ones on the display, which were probably taken from a trail high up on the other side of the pass.

So here are my “then-and-now” photos of Athabasca Glacier. Remarkably, accidentally, the two were taken from nearly the same viewpoint, but the camera optics are slightly different so you will have to mentally manage the foreground comparisons. Still, it is quite obvious that the glacier has receded from near the parking area (seen filled with RVs) to somewhere over the new terminal moraine!

Glaciologists have been aware of their diminishing extents for many years. My personal measurements, as obtained by my photos as a tourist, confirm the long-term trends, and I think just about anyone else as old as I am can also confirm that “winters in Minnesota are just not what they used to be”.

In 1970 the cause of shrinking glaciers was still a mystery, but over the decades, scientists have gained an understanding. Unfortunately, it will be difficult to reverse or even stop the warming trend. Gem Glacier, which hangs on the Garden Wall above Grinnell, no longer qualifies as a true glacier; it is a now just a “permanent snowfield”. Grinnell is less than half its size when I visited in 1970. Park rangers no longer lead tourists onto it— the melt lake is in the way. The prediction by the ranger that they will all be gone in a century seems to be on track.

I may actually live to see the final melting of Grinnell Glacier. So far the science predictions have been remarkably accurate. I am fortunate to have hiked on it, and other glaciers. It seems unlikely, but I sincerely hope that my grandchildren, as well as theirs, will be able to have that experience too!

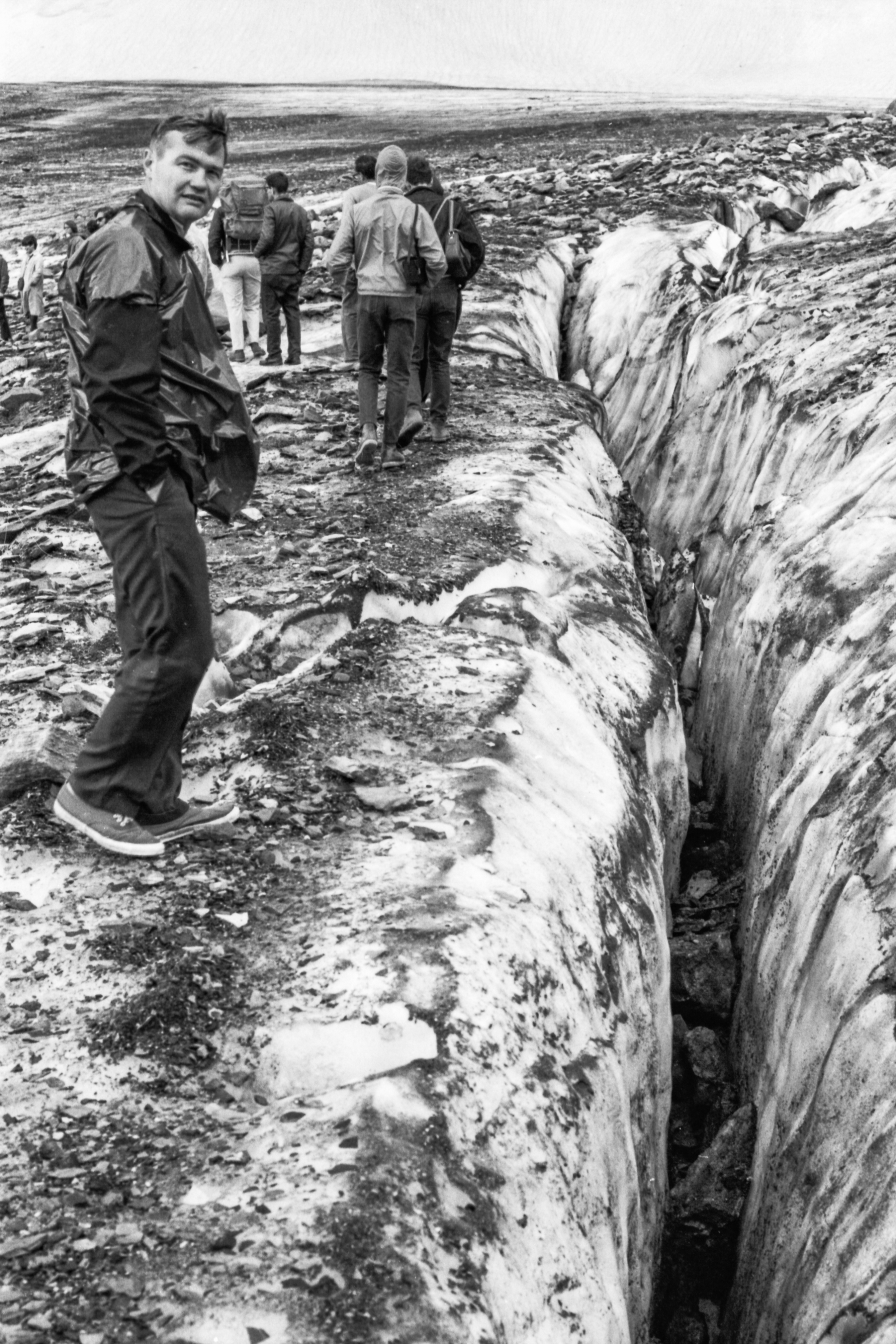

Here are some more photos from that first hike to Grinnell in 1970, scanned from my personally developed black-and-white Kodak Plus-X Pan film. Click to enlarge, click again to zoom in to the full resolution scan.

.