A half-century ago I was a teenager in high school, fascinated with cameras and photography. I had progressed from my first Kodak Instamatic to a (used) Kodak Retina-II 35mm; both are considered “rangefinder” cameras: you looked through a viewfinder that simulates what the lens sees.

But what I really wanted was a single lens reflex camera, a Nikomat, a camera one step down from the famous flagship product of the Japanese camera maker, Nikon. A “single lens reflex” (SLR) is a high-performance camera, where the view through the eyepiece comes through a complex arrangement of mirrors and prisms from the very lens that will be recording the picture. The key to this magic is a mirror on a spring-loaded hinge that provides the periscope-like view through the lens while aiming and composing the shot. When the shutter release button is pressed, the mirror swings out of the way just in time for the shutter to open and expose the film.

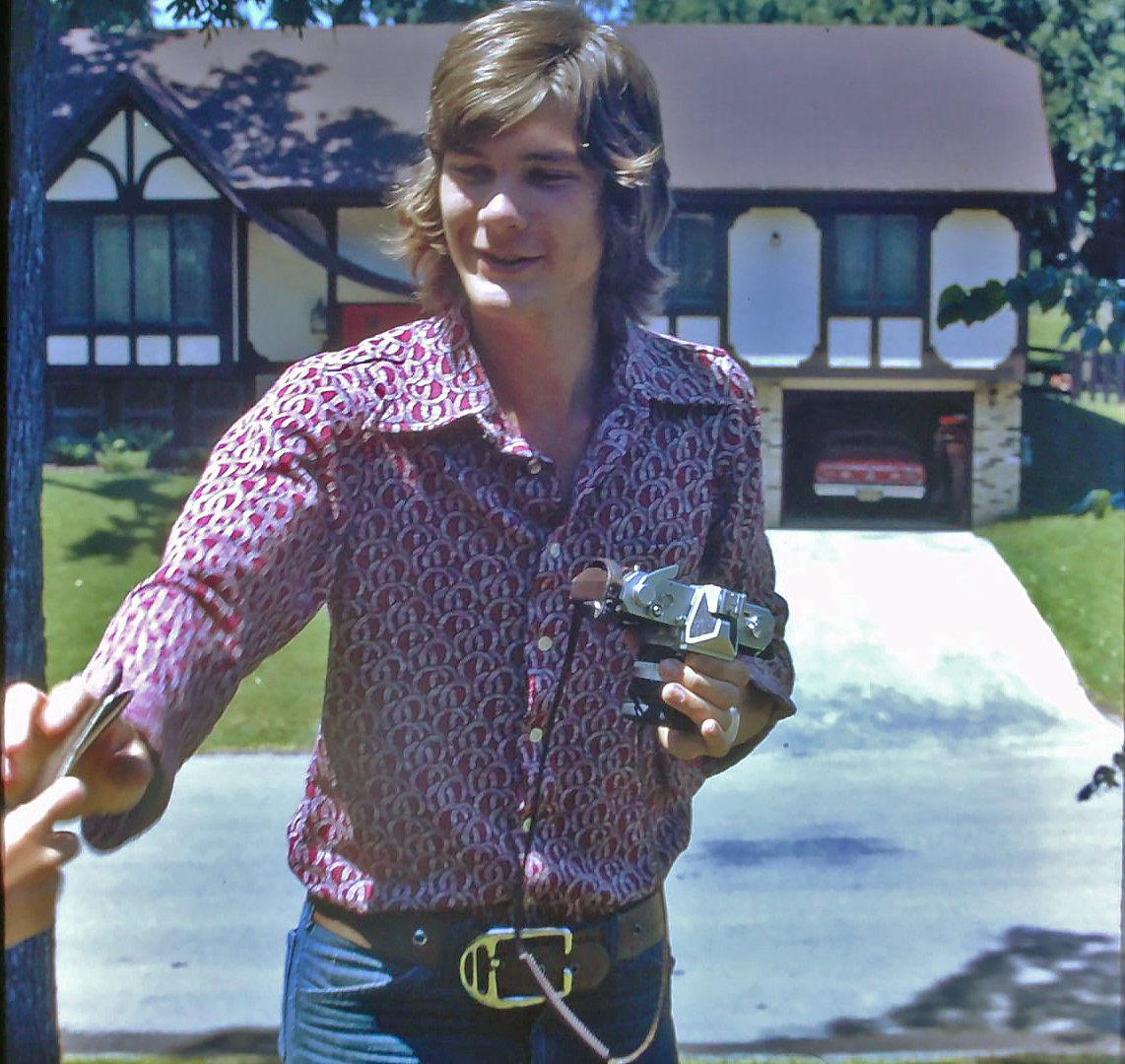

I acquired my first SLR by saving the earnings from my summer job flipping hamburgers at the local drive-in. Except it wasn’t enough. My dad helped out, not by a contribution, but by asking an associate who occasionally made business trips to Japan to make a camera purchase on my behalf, since the local cost was significantly lower than the imported retail price in the U.S. and, crucially, within my savings. At that time such long-distance business trips were rare, and I had to wait several more months for my camera to arrive.

I was thrilled to finally have such a wonderful camera in my hands, and I carried it with me everywhere. I was in the high school camera club and used my status as yearbook photographer to get out of various classes that I deemed unimportant compared to the events that needed documenting– sports, music, and drama events in particular.

During those years, the Viet Nam war had pulled Americans into the conflict, including my uncle, a recent medical school graduate. We exchanged letters while he was stationed near Saigon, and knowing my interest in cameras, he informed me that he could acquire one at small cost. But I already owned a nice camera. It had a good lens (all the Nikon lenses were highly regarded), but it was f/2, and there was a newer model at f/1.4, twice as fast!

I proposed to the camera club faculty advisor that the club could benefit from a low-cost camera to add to their small inventory that circulated among the club members. The plan was approved, and my uncle sent me a nice new Nikomat camera with the latest lens, which I silently exchanged with my older, slower lens before delivering it to the school. They were happy, I was happy, but I am not proud of the implicit deception.

My uncle continued his service in Viet Nam, surviving to return a few years later with some additional camera equipment that he had acquired. It was intended for someone else: his father, a longtime amateur photographer, but also a biology professor, who used cameras to record specimens and take images through the microscope. My uncle had acquired the most highly regarded single lens reflex camera, the Nikon Photomic FTN, along with a Medical Nikkor Lens and all the accessories to support it. I recall the day he presented these items to his father, describing him as “always generous to others, parsimonious to himself” and remarking that he fully deserved this collection of quality instruments. It was quite a gift, leaving a strong impression on us as my grandfather was moved to tears.

Fifty years later, I am now in possession of my grandfather’s Nikon and its remarkable collection of lenses and accessories. When I recently examined them, I marveled at the delicate and ingenious mechanical controls. The lens interacted with the camera body, the shutter, the aperture, the film speed, all via mechanical linkages – no battery needed. The shutter was driven by a spring force, accurate enough to time intervals from 1 second to a millisecond. The film advanced to the next frame, the shutter was reset, the mirror moved into place, the lens aperture opened, all by the stroke of a lever moved by your thumb! Simply amazing.

Photography has made enormous advances in the last 50 years. Electronics and software have elevated the discipline to entirely new levels; cameras contain computers and computers contain cameras. In my career I contributed to the transition from film cameras to digital cameras. Subsequent generations of creative engineers and artists have continued to push camera capabilities and as a result we are now inundated and surrounded by photographs. I am continuously amazed at the images I now see. It is easy to take pictures, it is easy to share them, (it is easy to modify them), and our world is changing as a result.

I can only try to keep up.