“Long before the term ecology became a part of the vocabulary of the scientist, primitive man, looking out over the expanse of blue-green water which characterized his favorite fishing haunt, was probably aware of the fact that notable alterations in the color and clarity of this body of water would occur as the seasons changed.”

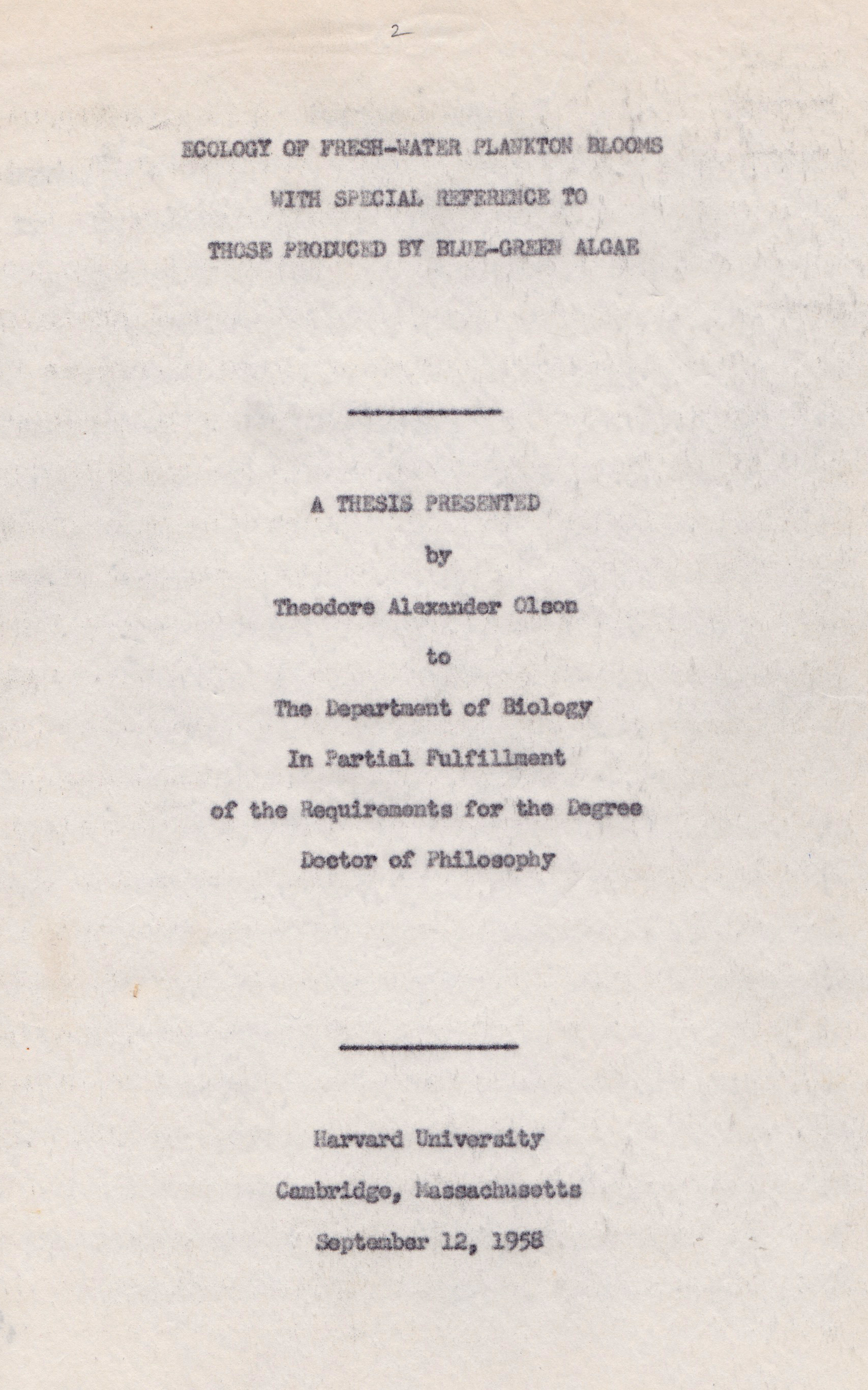

The introductory sentence of Theodore Olson’s PhD thesis on algae blooms.

I was witness to my grandparents’ transition to an assisted living apartment from the home they had kept for more than half a century. Though modest, it was the center of a busy family’s activities, and had accumulated the corresponding mementos through the decades. It had also collected the technical artifacts of my grandfather’s scientific career, specimens of insects and fish and algae from his ecological and entomologist specialties. He kept copies of his and his peers’ published works, along with those of his doctoral students, who carried on these disciplines, with the scientific rigor and methods that he taught them over their years in his tutelage.

I was there on the day when he had to empty the ‘wall of books‘ in his home library, which included the dissertations of his students. There was no space for everything at the new apartment. A few important reference volumes could be retained, but the others? What to do with them? Here were the compiled and distilled understandings of pioneers in biology, acquired through years of painstaking research, building upon the pyramid of human knowledge. These breakthroughs of their time have now been incorporated into our general understanding of modern biology.

What should happen to the first-ever photomicrographs of blue-green algae blooming to produce cyanobacterial toxins? What should become of the tabulated counts of seasonal species of mosquitos that were the vectors of mosquito-borne diseases? What should be the fate of that first chart correlating taconite processing and asbestos-like fibers in Lake Superior? All of these new discoveries had been first reported in his research and in the dissertations of his PhD students.

I once asked my grandfather about what it takes to gain a PhD. He told me that the student must find something that was previously unknown and advance our overall scientific understanding. This had quite an impact on me, someone who thought such things were very difficult (they are), but who imagined himself something of an inventor—creating things that had not existed before.

On that day of preparing to move to his new residence, I watched him select the hand-crafted volumes of dissertations by the numerous students he had guided over many years. They could no longer be retained in his reduced space at the new apartment. The photographic prints pasted onto typewritten pages that documented newly understood interactions between species no longer carried their original impact. The information had made its way into the mainstream domain of biology. My grandfather realized that these original documents were no longer essential. They could safely be returned to the universe’s overall random collection of atoms and molecules from which they had been assembled. The books were delivered to the local incineration/recycling center for our city.

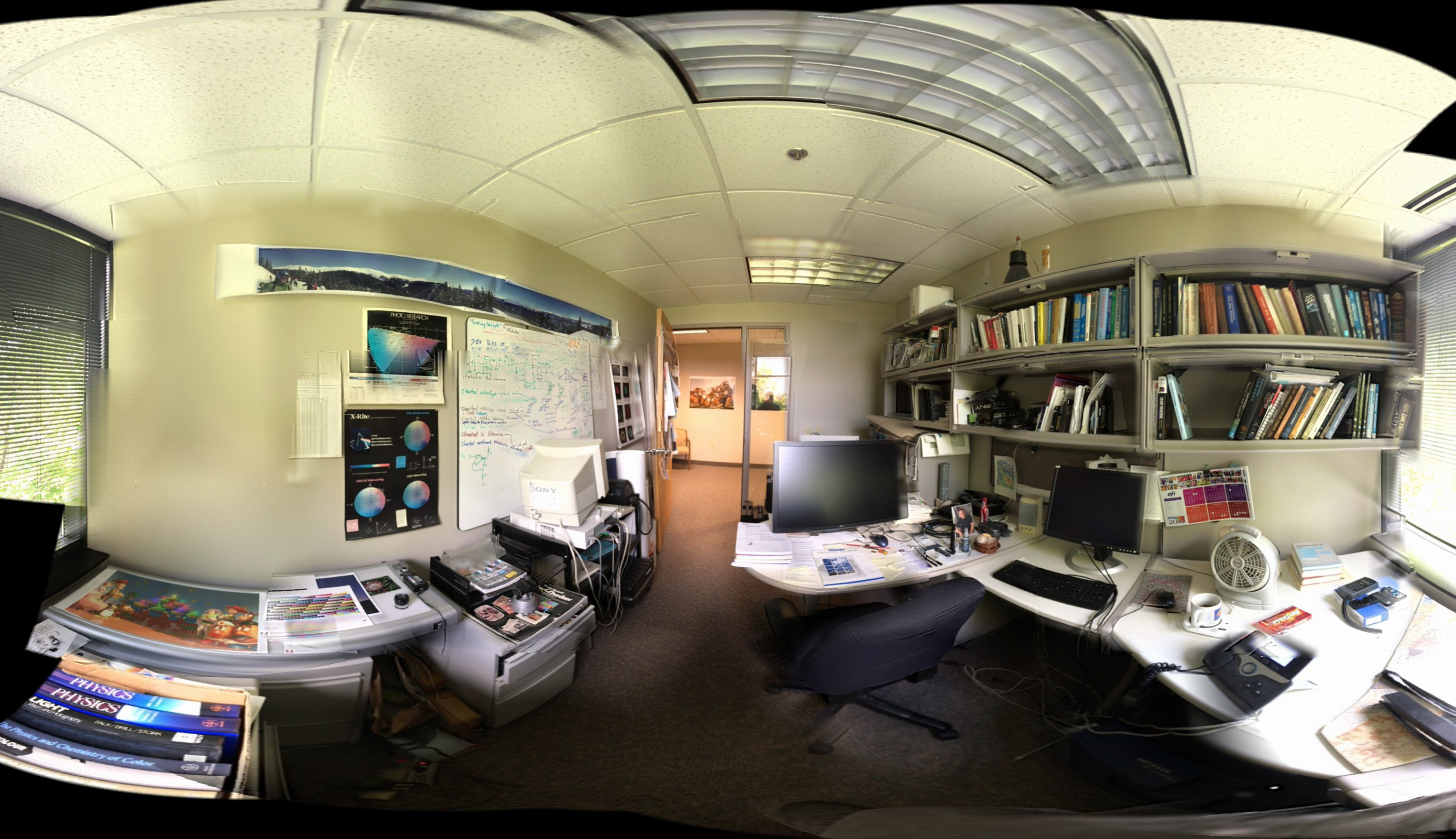

I have thought a lot about this in the years since. I am now in a similar position. In work over my long career I have contributed to the field of computer graphics and the transition to digital imaging. I reported on various discoveries along the way and was inspired by other researchers in the field. I accumulated many feet of bookshelves and file cabinets to hold copies of research articles and reference material.

Among my scientific lessons was the concept that data is precious and must be preserved. I accumulated dozens of lab notebooks containing my measurements, observations, theories and speculations. Most pages were mundane and had no particular lasting value. Yet there were many times when I referred back to entries made even years earlier in order to make progress on current research problems, some of which found their way into various patents and publications. Some of my results inspired others to advance the knowledge in this field in their own way.

The arcane details may be fascinating only to other color scientists, but they have had an impact even beyond that specialized community. Think of how easy it is today to take a good picture… with a phone! We all do it. A few decades ago most of us tolerated the hassles of using a camera to get blurred, under-exposed and tone-distorted prints capturing our kids at a birthday party or the family at Christmas. Now we routinely post beautiful pictures, including self-portraits, in perfect sharpness, and in brilliant color. These are the rewards of understanding the basics of color science and digital imaging, and I made a small contribution to it!

I harbor no illusions that there will someday be a writer who wants to review my letters and notes to help complete my biography. I won’t have a Wikipedia entry; my stature in this field is not equivalent to a supporting actor. It’s more like being an extra that had a brief speaking line to help carry the plot forward.

So what to do with those many feet of reference books and data files? Like my grandfather’s papers and his students’ theses, they were breakthroughs in their time, but have now been assimilated and incorporated into our understanding of the world. They have become merely historical, documents that charted our way but are no longer needed. Think about paper maps, replaced by GPS displays, which required a monumental amount of breakthrough science and engineering during this same time period. The early GPS experiments and data are now historical as well, but no longer essential. We have fully climbed out onto that technology limb; we won’t have to climb it again.

The landmark papers and references I have kept are still valid, still true, but are no longer needed. Their stepping stones have been used and are now behind us. We have new questions to answer, and the raw data that brought us to this point can be safely discarded.

Still, it is hard to discard it. My motivation for doing so is different from my grandfather’s: I now value the space it consumes more than the information it contains. In his case there was no choice, he was leaving his study containing the wall of books and he couldn’t take them all with him. In his time there were institutional libraries, but there was not a world-wide web of digital books and references accessible by a brief Google search. It should be easier for me to give up these academic artifacts, yet here I am, contemplating the value of my career’s work and the importance of preserving data, as I attempt to clear and organize my own, smaller, wall of books.

Pingback: Science or Sentiment, Generalized | Thor's Life-Notes