When Management Graphics adapted their film recording technology to support motion picture film formats, it was quickly adopted by movie studios to bring special effects from their computer memory images on to film. There were some problems however, and one of the most serious was the difficulty in obtaining the full brightness range found in typical scenes, especially when they included lights—candle light, desk lamps, car headlights, streetlights. Any light source, even a glimpse through a window to the bright outdoors, would cause a large flare in the final film frames, washing out detail in the scene. Our customers complained, and we started down a path to research and solve the problem.

We understood what the fundamental issue was: halation, an effect caused by the glass faceplate of the cathode ray tube used for creating the image. The bright spot on the phosphor screen was internally reflected at the glass surface which then illuminated the phosphor coating. If phosphor were black, this would not be a problem, but phosphor coatings are white, as are most materials made of fine powder, and it resulted in this internal reflected light overexposing the film. In the absence of a black phosphor, there were few other ways to mitigate the halation effect.

One of our customers was incorporating our film recorder into a full workstation system. Quantel, a company in Newberry, England, had become successful in the early years of digital video and was looking for a way to expand its editing tool offerings into the motion picture market. Quantel’s engineers understood the halation problem as well, but they didn’t want to rely on our figuring out a solution: they had an aggressive development schedule.

They came up with a mechanical solution, basically a travelling shutter that would mask off the unwanted halo on the phosphor: a slit, that moved in coordination with the raster scan on the screen. A full exposure took 30 seconds. The slit would track the scanline as it slowly progressed from the top to the bottom of the frame. It would then reset its position back to the top and repeat for the next frame. The problem was knowing how to synchronize the shutter movement with the moving scanline.

David Throup was the Quantel engineer who was responsible for solving this problem. He had devised the travelling slit mechanism and made a proof-of-concept prototype. He then approached us to help solve his final obstacle: he needed an electrical signal to indicate the start of the raster exposure process.

I met David Throup twice. First, when he made a business trip from England to visit our small company in a suburb of Minneapolis seeking assistance with his solution to the halation problem. We were skeptical, probably because our expertise was in electronics and software, not mechanics, but entirely willing to provide the information he sought. We identified a signal on the logic board inside the film recorder and he happily tapped it to trigger his slit mechanism.

Quantel went on to become a valuable customer for MGI, purchasing dozens of our machines to integrate into their workstations, enabling their customers to create wonderful special effects for their motion picture projects.

The second time I met him was almost an accident. I was in the UK on business for an entirely different purpose—to explore a new imaging technology that did not involve wet chemistry to develop film. At the end of the trip, there was an extra day, so I requested a last-minute courtesy visit to Quantel. David took me in and showed me the factory floor where our film recorders were being modified with his traveling slit invention. I got to spend time in their screening room to see the results—films with scenes that showed remarkable beauty and contrast, including bright light sources that moved in and out of view with no discernible degradation of detail. I also was given a demonstration of the novel features of their workstation.

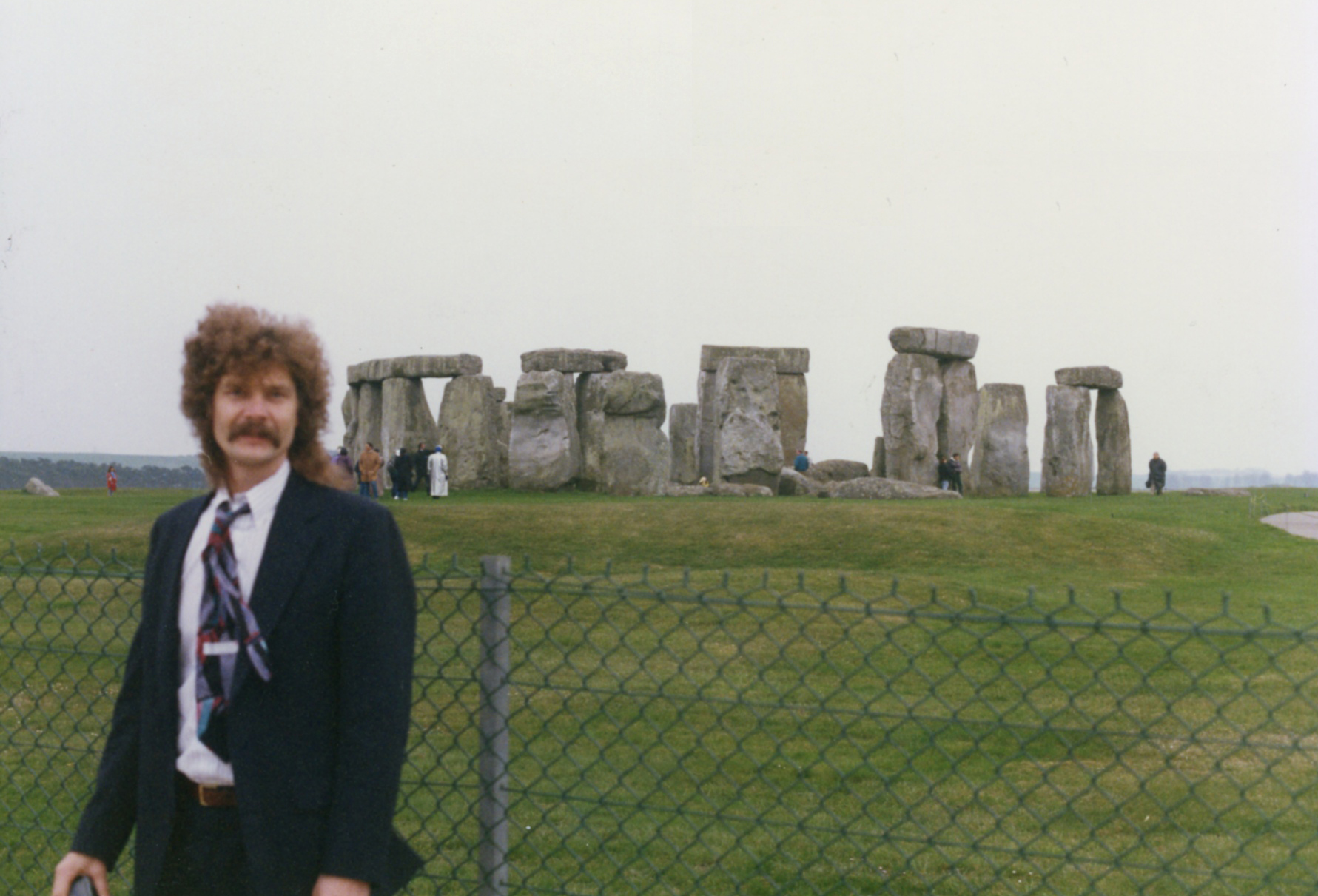

During this cordial exchange, I made an offhand query. I wondered if it was true that Stonehenge was in this area of England and if so, how could I best see it? Well, this was evidently just the excuse David needed to exit what must have been a tedious business obligation, because he abruptly ended the demo and suggested we immediately drive there!

To my great relief at not having to drive the left-handed roads, he escorted me in his car. It turns out that Stonehenge is not an isolated monument. There are other “henges” nearby, and on the way to our destination, we went past Woodhenge, a circular layout of wooden timbers. We also stopped at Avebury, the site of a circular array of stones even broader than Stonehenge.

I was surprised that the route to all these monuments was along our equivalent of “back country roads”. They were two-way, but one-lane, roads through the English countryside where oncoming traffic simply negotiated, somehow. There wasn’t much traffic to negotiate however, so we proceeded without incident to Stonehenge.

I found it to be refreshingly isolated. As famous as it is, there are no commercial tourist centers around it. A fence protects the immediate area, and access is restricted. We were moments too late in the afternoon, the gates had closed, so I was unable to walk among the megaliths. Still, it was thrilling to personally see them in their bucolic setting.

David then took me to his home, where he had earlier requested his wife to “put the kettle on”, meaning to host me briefly when we returned from this excursion. I was expecting a cup of tea, but instead it was a full English dinner. It was delicious, and I enjoyed their company for this unexpected treat in the intimacy of their home. It didn’t end there. After dinner I got to watch British television with their young son, an episode of Benny Hill!

I had seen Stonehenge, an admired example of pre-historic technology, guided by the man who could claim credit for being the first to make halation-free images from the Solitaire film recorder. All in all, it was a marvelous experience, one I had never expected, and one I have often wished I could reciprocate.

A few weeks later, after I had returned to the US and resumed my work testing our optical solutions for the halation problem, I received an overseas package from David Throup. It contained a beautiful book about Stonehenge and further information. It was a very thoughtful gesture and solidified my view of him as not only a brilliant engineer, but also a wonderfully kind and considerate person.

I recently encountered the Stonehenge book while curating my “wall of books”. I hope this story of how that book got there will increase its value to any of my descendants who may encounter it.