The sun sets fairly late in the day at this time in summer, and the stores and vendors start to close shop. The tourists, with fewer entertainment options, start to depart, finding their cars and campers in the parking lot, gathering their family members, and negotiating their way out of the lot as if a movie had just ended.

I am now hiking upstream through this traffic with my camera equipment and tripods. It is a lengthy hike, and even though I have refined my methods for lugging this stuff, it still requires an effort that leaves me slightly panting when I can finally drop the camera bags and set down the tripods.

It turns out that I can set my stuff down almost anywhere on the Old Faithful boardwalk, since it is devoid of people and traffic, an eerie condition I’ve not experienced before. With so much choice, where do I pick?

I have three cameras, three tripods. Redundancy is the antidote to the likelihood that many things can go wrong. I make lots of mistakes, and don’t always know how best to take the shot, or what shot to take at all. I have some time to think about it while waiting for the next eruption.

The eruption of a geyser, however, is not an event that can be timed with astronomical precision; it is a random event that has an expected timing, but with large uncertainties. I need to be ready, significantly before the posted average time, and be prepared to wait, vigilantly, for its preamble signs of eruption.

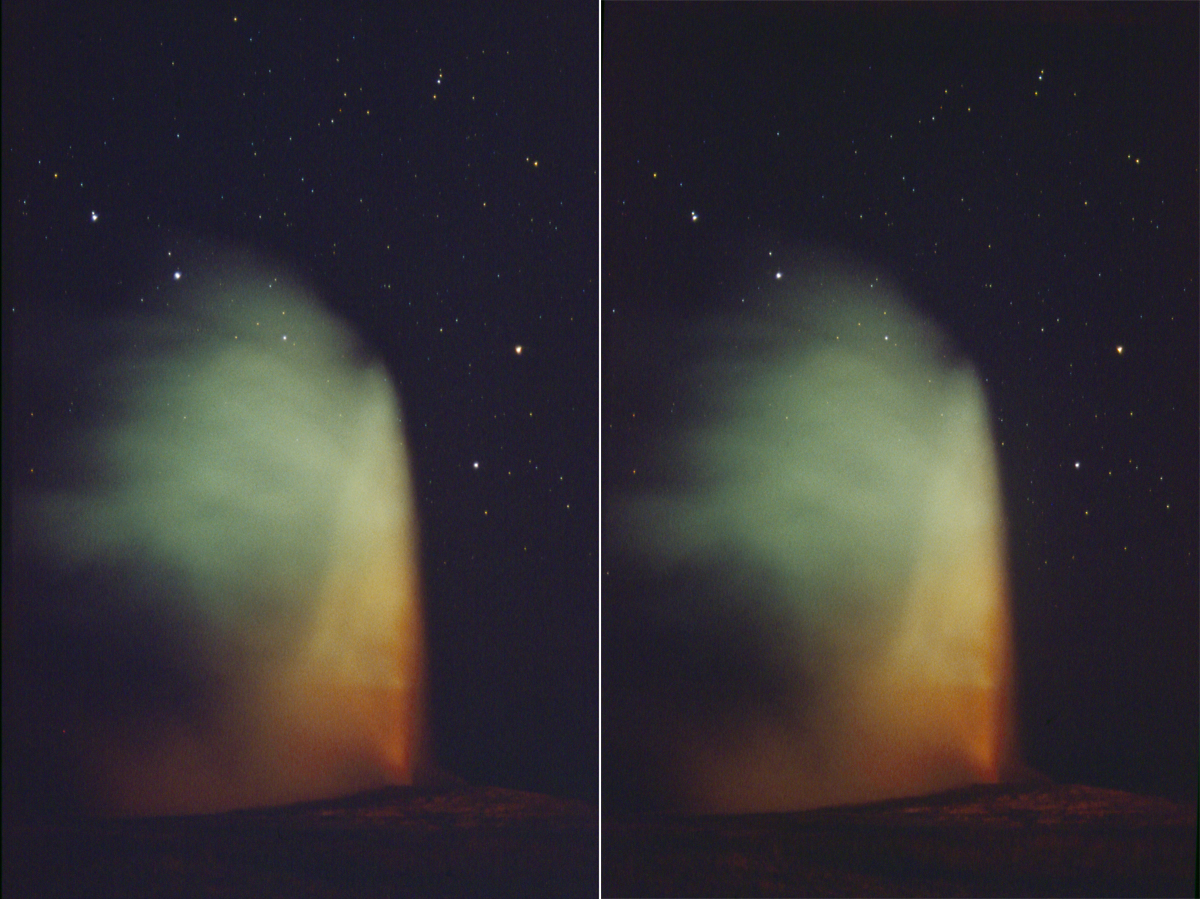

With my cameras set up, all within arm’s reach of their shutter releases, I looked around at my environment. I had feared that it would be too dark for anything to show in a nighttime photograph, but I was bathed in light. Even though the stores had closed, their lights did not go out. The hotels catered to guests all night, and even though almost nobody was on the boardwalk with me, there was an unseen surrounding ambience of people.

The parking lots needed lighting (of course), and as the people found their cars and started them up, headlights would beam the horizontal distance between the parking lot and the geyser basin, cutting across anything in its path. Often the headlights would be on, even while the car was still parked, as its occupants organized themselves for the drive to their nighttime destination. All of these sources of light ensured that my cameras would see the geyser’s eruption when it happened.

It might even be too much light. I wondered what exposure I needed to record the rush of water, but still capture the background stars. Could I get both on the same frame of film? Another reason for multiple cameras: multiple exposure experiments. I waited, as if on call, and during this time could guess and re-guess the exposures, convincing myself of one solution, then re-assessing and convincing myself of another. Such is the hazard of unoccupied time.

Eventually, the guesswork was interrupted by a gurgling spurt from the geyser. A belch of steam. Another. Don’t burn your film yet, this is just the warmup act. The spurts get bigger, the belches louder, a recurring pattern seems to be building, and then… quiet. Did I miss it? Was that the actual eruption and I was expecting something more? Do I have to wait another hour and a half? As I was kicking myself for being too smart about these things, the geyser came back to life and started pumping water. Like a fountain, it created a vertical column that stood for a moment then fell on top of itself. It pumped another column, higher than before, and then fell down again. With each jet reaching higher than the previous, steam poured out and up and drifted with the wind, making a white curtain to catch the light.

I started tripping shutters and timing in triplicate, each camera having a slightly different sequence of exposures, hoping that somewhere in the set a successful shot would result. The geyser spewed water for over a minute, but that was hardly enough time to get more than a few exposures with each camera. My hectic moments attending cameras matched the furiousness of the eruption.

As the water column now diminished with each surge, I relaxed a bit and watched the steam drift with the wind down the geyser basin. I looked around and saw a couple, watching with me, but then turning to each other and enjoying the moment. It had been a private showing, just for us. The couple moved on, to be absorbed into the distant human background, leaving me to pack up my equipment and contemplate this event as the geyser returned to its normal mode, waving a small white flag of steam.

In another ninety minutes or so the geyser would spring back to life, raging with hot water and steam. Would there be anybody here on the boardwalk at that time? Maybe, but it must certainly be true that a geyser erupts in the dark, even when there is no one to see it.

With my camera redundancy, I obtained this stereo pair, presented here for cross-eye viewing (look at your finger, six inches from your nose and centered between the pictures, then relax your gaze to view the central superposed image).