When I was twenty or so, I built a clock. It was a clock that used electromechanical relays to count the seconds, minutes and hours. I was early in my electrical engineering studies and barely understood Ohm’s law, but I was aware of electromagnets, and how they could be used to make mechanical movements. Some of us call them solenoids, coils of wire that magnetically push or pull an iron piston to make and break switch contacts.

My dad, in his ham radio hobby quest for cheap electronic components for whatever future project he might undertake, had acquired various relay mechanisms. He showed them to me and explained how they used electrical pulses to move a metallic wiper to a series of successive contacts. These were telephone relays, used when you “dialed” the phone. One relay, responding to a single rotary dial action could connect you to ten possible neighbors. Cascading it with another set of relays would allow calling up 100 neighbors. More phone digits would extend it even further, you get the idea. I barely understood how to deliver current to energize a relay coil, but I could figure out how to connect the contacts to make a sequence that counted.

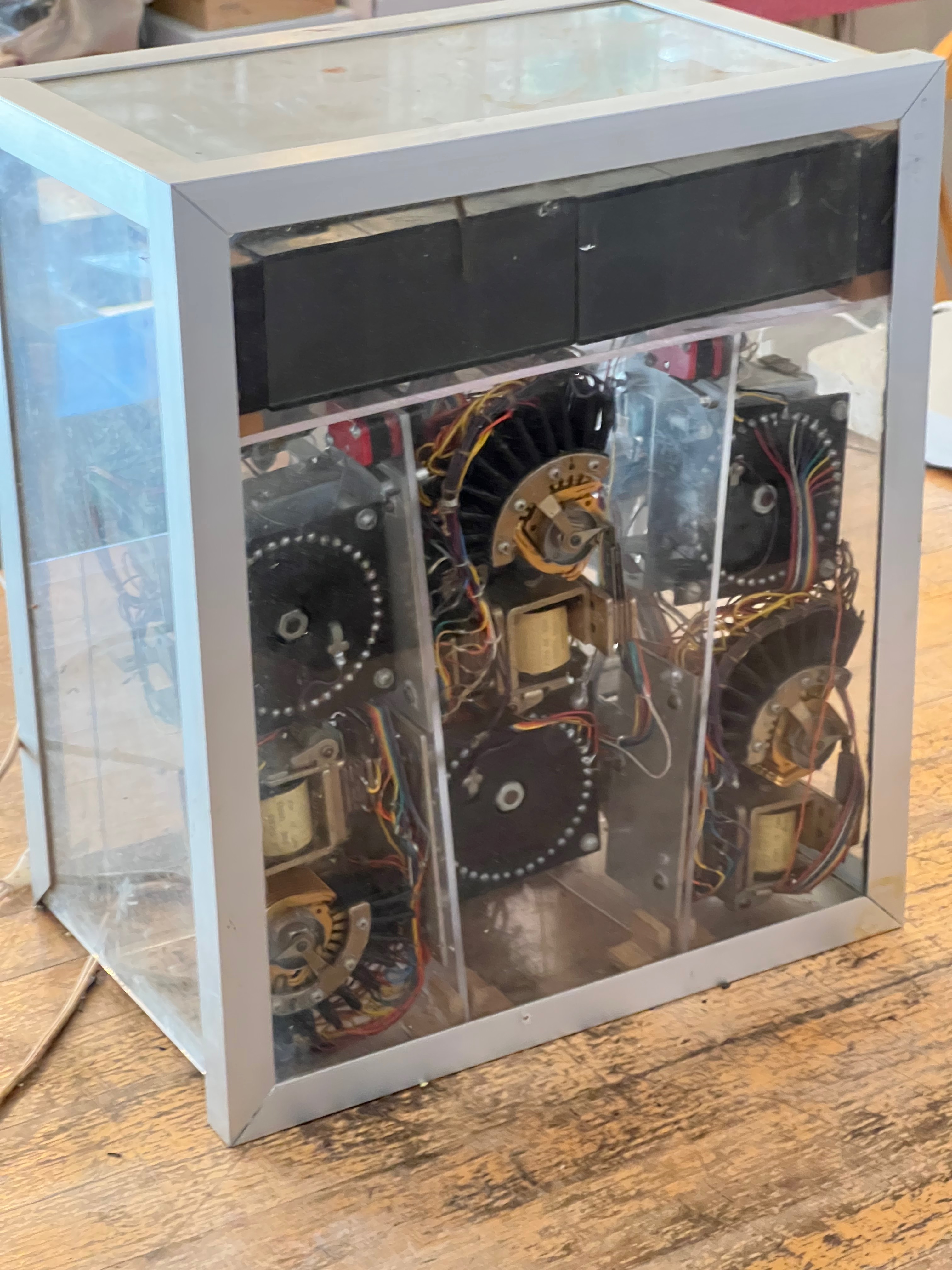

Another item from my dad’s ham shack inventory of salvaged components was a numeric display, something you might see in an elevator (60 years ago) indicating the current floor. It used incandescent light bulbs to project a numeric figure on the screen. Ten separate bulbs, each behind a number glyph mask; one of which was selected for the current digit value. I figured out how to connect the telephone relays to the elevator displays to make a clock.

I was quite pleased with the result and when I got it working, I showed it off to my friends. But it had several drawbacks. First, it was noisy. Relays are mechanical devices that magnetically pull metal contacts against each other, resulting in a click-clack noise as they activate and release. The relays counted seconds, so there was a click-clack noise every second. And at ten seconds there was an additional click-clack, as the next relay responded to the carry pulse. And at 59 seconds, there was a carry to the minute-counting relay. As the carries propagated to the hours, a peak acoustic disruption occurred as the clock transitioned from 12:59:59 to 01:00:00.

The other drawback was that the clock got hot. As I said, I did not yet understand the relationships of voltage, current, power and heat. I just hooked up the components to make the displayed result I wanted. The numeric display, comprising light bulbs, used quite a bit of power. And the relays required power too, and my power supply was terribly inefficient. As a result the clock, in the glass case I made for it, built up an enormous amount of heat. I tried to ameliorate it by installing an internal fan, but this seemed only to make things worse (the fan used power too).

I kept the clock as a curiosity piece, displayed on a fireplace mantel in our home. It was intolerable to run continuously, so I would switch it on to show visitors that it actually worked, and then shut it down to stop the noise. Eventually, the clock got packed up during one of our moves and stayed so.

The boxed-up relay clock was in storage for at least 30 years, but I would occasionally encounter it hiding among my workshop parts and supplies. I recently ran across it. It had endured the desecration by (and excrement of) rodents, the decay of electrical components, and the binding of mechanical joints. I wondered why I had saved it all these years.

Well, the idea of resurrecting a contraption that I built half a century ago carried a certain appeal to me. Having since learned the principles of electricity, maybe I could bring it back to life and its former geek glory!

In the next series of posts, I will describe the process of restoring this pioneering clock.