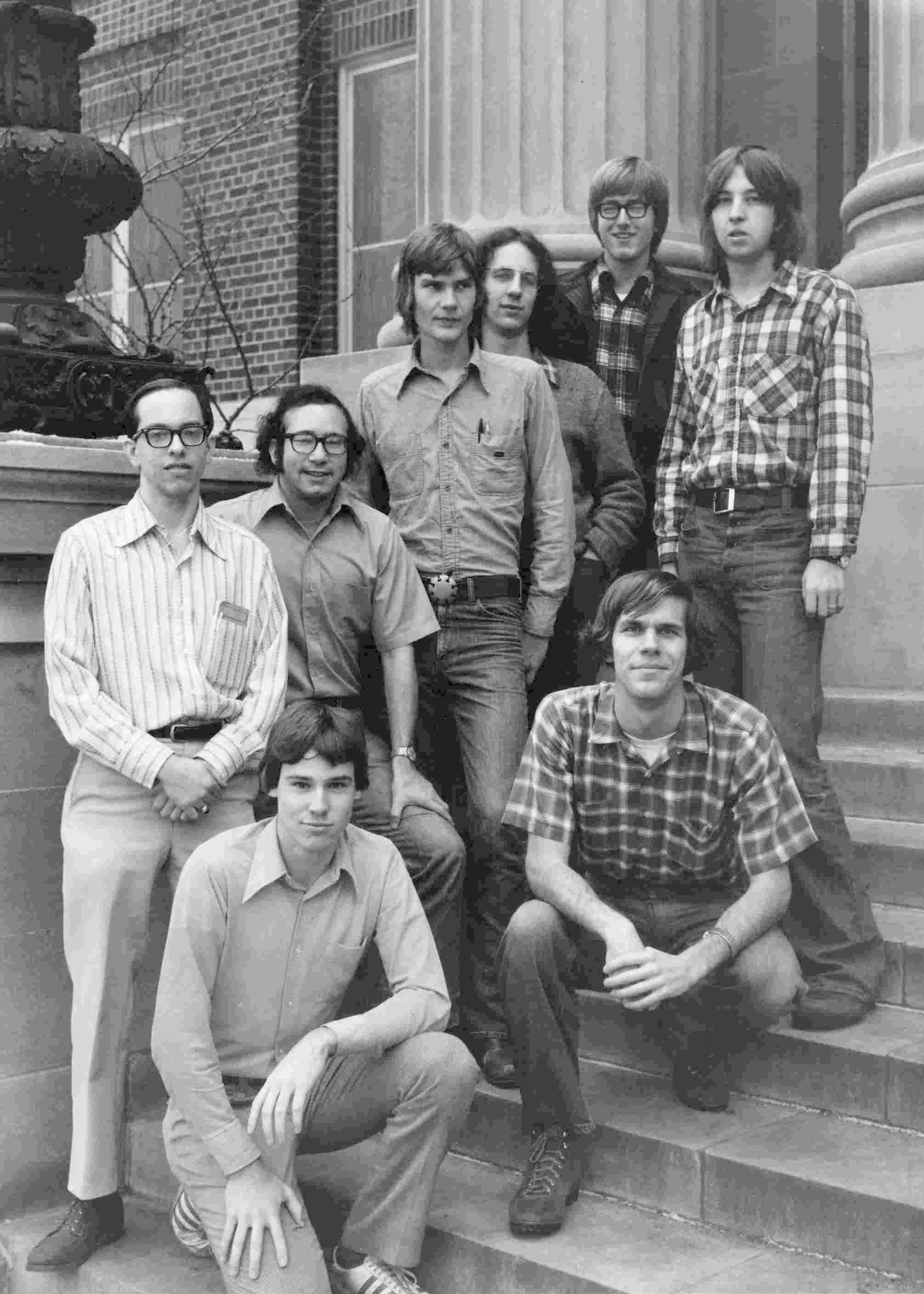

Standing, left to right: Kevin Loeffler, Richard Dorshow, Thor Olson, Jeffrey Harvey, John Bowers, Kevin Thompson. Squatting: Greg Hull, Curt Weyrauch.

I first attended the University of Minnesota in the fall of 1971. I was accepted to the Institute of Technology, IT (now College of Science and Engineering, CSE) but faced the difficulty of narrowing my interests which ranged from science to art, from mathematics to theater. My initial major, architecture, was inspired by a desire to combine art and science, romanticized by the Ayn Rand novel “The Fountainhead”. That idealistic goal was punctured by the first lecture of Architecture 101, where in retrospect, I recognize that the professor portrayed the profession in its worst possible light in order to weed out students who were not fully and utterly devoted, focused, and dedicated to the field.

It worked. I changed majors the next day.

But I was still registered for all the courses required for training in architecture, including math and physics, important for structural analyses to guarantee the strength and safety of buildings. I continued these courses, and even while shifting my major to Fine Arts, I still wanted to learn “the secrets of the universe”. Eventually, I found the reliability of science to be more aligned with my internal quest than the apparent arbitrariness of the art world. Don’t get me wrong, I admire artists and consider them to be explorers, and the reports from their journeys inspire and motivate me. But I realized that I did not have the qualifications to lead or undertake those journeys.

Instead, I focused on how Nature works; this is the domain of physics. And I found myself in a small group of classmates that were similarly enthused. Somehow (I don’t remember the details), we became members of an informal club, “The Roving Photons,” whose motto was “A roving photon gathers no mass”. We attended the same classes; were confronted with the same contradictory anomalies of quantum physics and we all struggled to make sense of it.

I like to brag about the classmates I studied with. One of them, John Bowers, went on to become a leader in the field of photonics (appreciate your fiber optic internet connection) . Another, Kevin Thompson, contributed to the corrective optics for the Hubble Telescope.

My freshman dormitory colleague Craig Holt, discovered an important physics-mathematical relationship, now named after him, as is an endowment for a scholarship at the University of Minnesota. My roommate during our junior and senior year, Jeff Harvey, went on to become a physics professor and contributor to string theory. Others became teachers and engineers, extending our knowledge of the universe and demonstrating how to utilize it, to the next generations. It all started in our undergraduate classes at the University of Minnesota in the 1970s.

Here is the recollection of one of my classmates and Roving Photon member Richard Dorshow (who later contributed to the development of medical devices and pharmaceuticals), as reported in 2010 by the newsletter of the School of Physics and Astronomy.

“…One of my favorite memories was from my sophomore year. A small group of us formed an undergraduate physics club, The Roving Photons. I was elected Executive Director, mainly because I wrote the rules for election and eliminated the competition. It was a very friendly group of comrades (Greg, two Kevins, Jeff, John and Thor). We were given a small, narrow room in the sub-basement of the Physics building.

“There was an exit sign in the hallway outside the door. Thor, who was also an art major, somehow put the club name on two pieces of glass and we replaced the exit sign with the glass such that we had a lighted club sign. I think the sign lasted less than one night as it apparently violated the fire safety code. We had a refrigerator in the club room and arranged a delivery of pop every so often.

“Our main impact was a faculty lecture we sponsored and arranged. We would take the faculty speaker out to lunch on the day of the presentation. I remember we used to go to Sammy D’s. I think our first speaker was Professor Gasiorowicz. [He was] a favorite, whose explanations of probability usually involved some sort of food analogy: a tablespoon of peanut butter spread over a cracker, many crackers, and then the entire universe to explain probabilities. I still have an autographed copy of his book written and completed during my time at the university.

“The school used to get audited by the American Physics Society and a group of distinguished physicists came to do the audit. This included William Fowler, then president or president-elect of the APS, and also the famous physicist Herman Feshbach. Because there was an undergraduate physics club, the distinguished group talked to us too. Here we were with this group of esteemed physicists and we were telling them about the lunches at Sammy D’s, and the soda pop delivery. In hindsight, this seems a very surreal event.”

Rick’s description captures only a small portion of our experience as students during the 1970s, a turbulent but productive time in physics. A “zoo” of new subatomic particles were being discovered, all of which would be clues leading to the now famous “Standard Model” of quantum mechanics. We were in the middle of it all but didn’t really know. To me, it made little sense.

And it is still challenging. Although I was distracted from my study of physics by the exploding field of electronics brought on by miniaturized transistors (and because just about any physics experiment requires electronic instrumentation), I continued to follow the developments in physics throughout my career. Reading their Wikipedia entries, the inspiration from my superstar classmates of 1975 is part of why I am still curious enough to engage in online courses for learning how to program a quantum computer.

The quantum “measurement problem” has not yet been resolved to my satisfaction, but Schroedinger’s cat is being cornered. The recent measurements of gravitational waves, the unexpected acceleration of the universe, dark matter, dark energy and other fascinating observations may be today’s equivalent of those confusing 1970 particle zoo clues, pointing us to a “New Standard Model”. I hope someday to learn about it!