This is adapted from a tribute that my father made at the memorial of his father, Theodore Olson, after whom we are both named, who died in 2002 at the age of 97. I post it here for the online access of posterity, and to provide a portrayal of the scientific mindset of a family patriarch that influenced not only his students, but his entire family and several generations beyond. Here is my father’s rendition of our family history.

The start of this story goes back almost 150 years. In about 1860 in Norway, Hans Opjörden left home and went to Oslo. Hans had the misfortune to be the second son in his family, and that meant that his older brother would inherit the family farm. Hans left home and headed off to Oslo, where he went to work in a shipyard building boats. After a while he decided he really wanted to sail on the boats instead of just building them. At this time Norway was a province of Sweden. Shrewdly, Hans changed his name from Opjörden to Olson (with a Swedish spelling) and got Swedish sailing papers.

He went on several voyages and along the way befriended a shipmate named Peter Magnus Peterson. We can imagine a conversation between them based on what subsequently happened. Hans confided that he’d really wanted to be a farmer but had no prospects of getting land—and that being a sailor was not his “dream job”, but was good paying employment.

The shipmate advised him, “You should go to America where they are giving away farmland!”

“But I heard they were only giving it to citizens—and not to new immigrants.”

“That is true, but you are in luck! My sister in New York is a Civil War widow and she’s a citizen. If you marry her, she can apply to homestead a plot of land!”

And so, in June of 1868, Hans Olson landed in New York and went to Chautauqua, and two months later married Caroline Peterson Franke. There was a problem however. There was no homestead land in western New York—they would have to go to the Midwest for that. A second problem was Caroline, an educated woman, had four children and she wanted them to also receive a good education. So, she left her children to be raised by family members and attend Eastern schools, and set off with Hans for Minnesota where good land could be found. They settled in Atwater, Minnesota and soon after establishing their homestead, Caroline started a school for the community and served as the teacher.

Hans and Caroline had a single child, Hendrick Martin Olson, known as Henry. Although initially taught by his mother, he continued on to a public school that ran through the 6th grade. He was an intrinsically curious and bright young man who read and studied on his own after completing this basic education. His talent was recognized by the community and they raised enough money to send him to the Swedish Seminary in Chicago to become a minister. By the time he returned he was fluent not just in Norwegian, Swedish and English—but he could read Latin and Greek.

Henry married the ‘girl on the farm next door’, Anna Rachel Anderson and they had two children Theodore and Marie. Theodore, known as Ted, was my father. By 1910 Henry, Anna, Ted and Marie were living in Kingston, a small town near Dassel, Minnesota. Henry had a very small Swedish Covenant congregation in that community, not enough to fully support a minister, so Henry and Anna lived on and worked a farm just outside of town.

Reverend H.M. Olson, as he was known, loved to read and had a significant book collection for a poor minister in the early 1890’s. I have occasionally tried to imagine what it might have been like being that educated in a community where almost no one had completed high school.

My father told me that before he started school, he spoke only Swedish and Norwegian. When he started first grade he was introduced to English. Later, in college he would become fluent in German and French and at one point in his 80’s he was studying Spanish.

Kingston was a tiny community, and so he had to go to high school in Dassel, the neighboring town. Because the 11 mile distance was a long travel time away, he lived in a boarding house during the weekdays of the school year. He was valedictorian of his class, but because he was so nervous speaking in public his best friend, Elmer Marks, agreed to give the valedictory speech at graduation. The idea of my father being afraid to speak in public seems totally alien to the person that all of us knew.

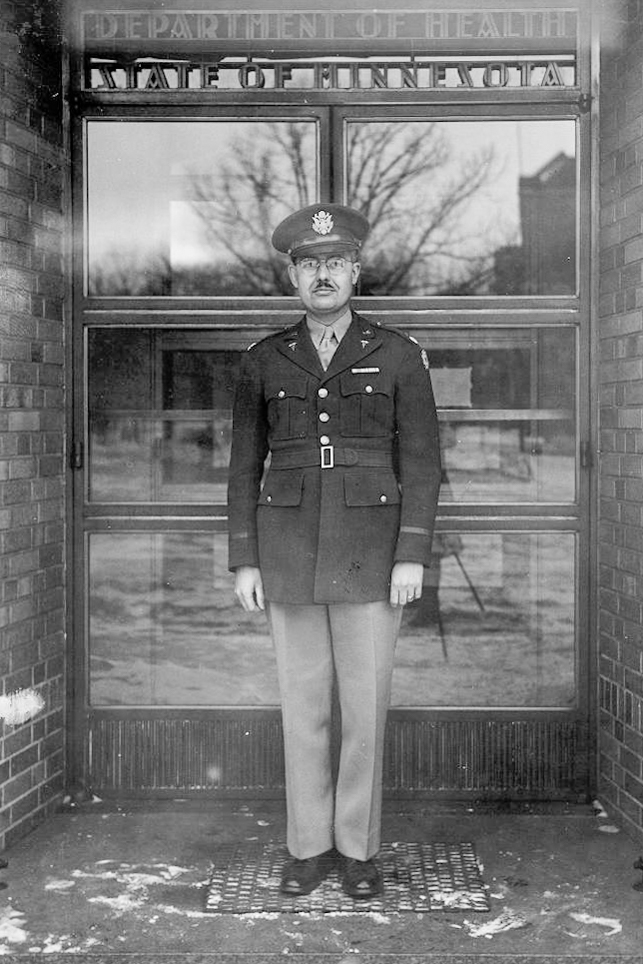

After high school my father went off to the University of Minnesota where he worked his way through college, and then to Harvard to gain a Master’s degree in biology. He truly enjoyed learning things and to that end collected many books, most of them scientific in nature. During World War II he was sent to San Antonio, Texas to develop procedures for teaching people how to identify dangerous mosquitoes and how to control them. This was prior to DDT when malaria and yellow fever were a real concern for troops in Africa and the South Pacific. Because his personal reference library on these subjects was better than anything the Army had, they shipped his books to Texas.

After the war the US Government shipped the same material back to Minnesota. The government being the government, the books were sent home in large, incredibly well-built, hinged-cover boxes that only the military could afford to build and ship. For years my mother stored things in those boxes and today at least three of the boxes are still in use some 45 years after their construction. They give every appearance of being good for another 50 years.

My father resumed his academic career, completing his doctorate at Harvard and returning to the University of Minnesota where he continued his research and expanded his teaching of graduate students in Public Health. For the references needed to prepare lectures, and for storing research journals, reprints, and clippings of news articles, he decided to build a bookshelf in his study. By the time it was finished the shelf was actually a wall of books and files that extended from the floor to the ceiling. At the bottom of the wall he had built file storage so he could store the material for his lectures and have it handy as he prepared for the next day’s classes. I have the clear recollection that my father encouraged everyone to get plenty of sleep with early bedtimes so that he could stay up well after midnight planning what he would be presenting the following day.

As he changed his focus from diseases borne by insects and by poor sewage treatment to the study of the ecology of Lake Superior, he was forced to build a second wall of books. Later he filled my old bedroom with books and when there was no space left there, he started filling the room of my brothers Tom and Bob as well.

My brothers and I grew up with the ‘wall of books’. We learned that family squabbles which involved facts, or the meaning of words inevitably were terminated by orders from my father for the participants to “go look it up!” and come back with the answer. After a number of years of this it became second nature to go off to his library to look for information, to his dictionary for word definitions or to his thesaurus to find a word that we could use in place of another in something we were writing. By the time we left home we sort of assumed that everyone had ‘a wall of books’ or else how could they manage to get along in life.

When he and my mother moved to Park Shores Apartments in St. Louis Park about five years ago many, many books and papers were sent off to the University Library or to used bookstores for recycling. In spite of that major effort to reduce the wall of books, there were still too many for the single wall bookcase that is the Park Shores standard. My brother Tom was pressed into service to install additional book shelves to accommodate the overflow. In spite of his best efforts my father managed to buy books faster than Tom could put up shelves. Even today there is an overflow of books in their apartment at Park Shores.

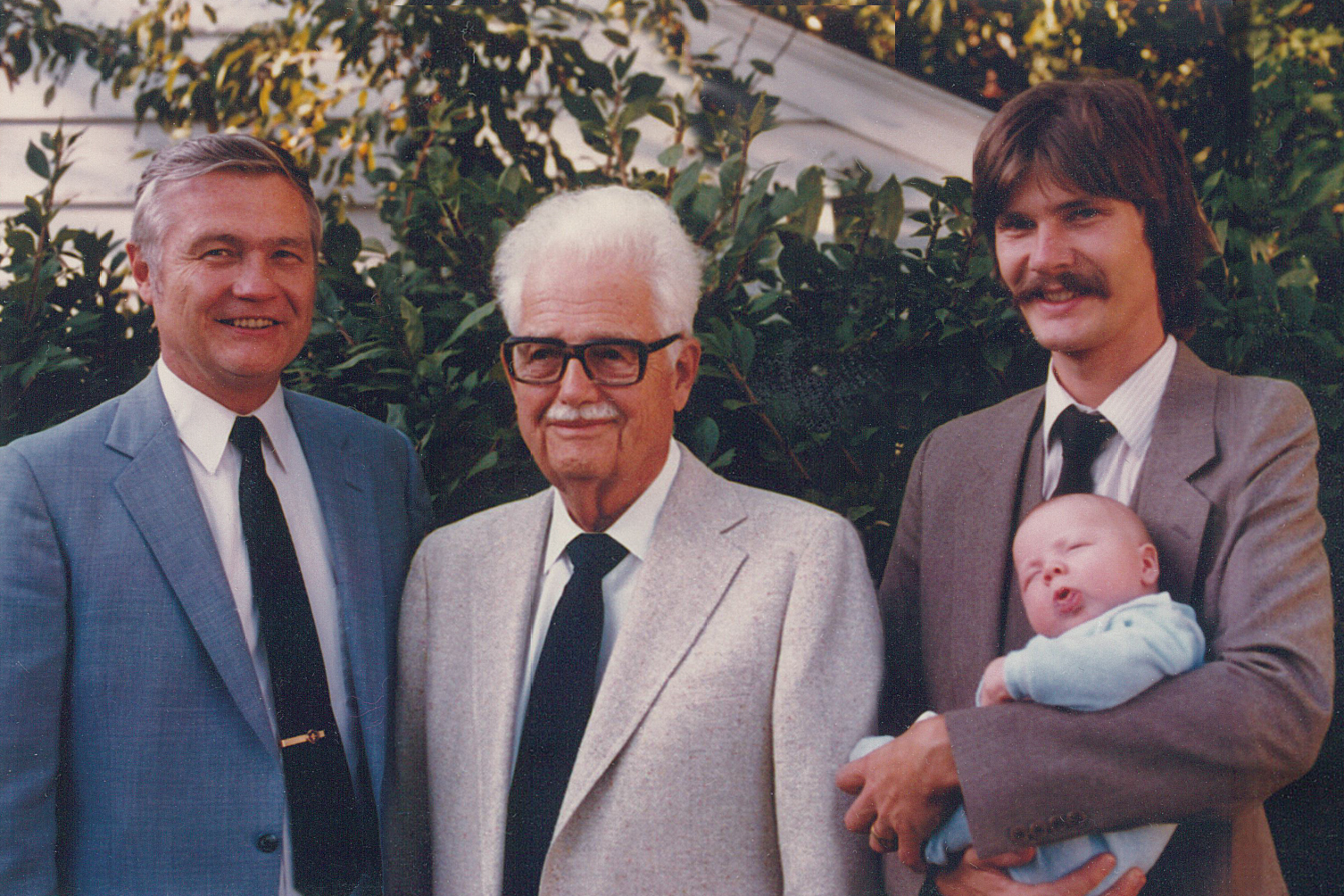

By itself that would be an interesting story, but it doesn’t end there. If you go to my house or my brothers’ houses you will find ‘a wall — or two or three — of books’. If you go to my son Thor’s house, you will find that he is seeking the world record for ‘book walls’. And his brothers and sisters have walls of their own. I fully expect that as my nephews and nieces establish their homes that they will also provide space for books. Each of us is comfortable with the thought that we will spend the rest of our lives learning about things. This interest in education which goes back to my great grandmother Caroline Peterson Olson and from her to my grandfather Henry Martin Olson and from him to my father Theodore Olson has moved through two more generations as evidenced by my brothers and our children. The next generation of my father’s great grandchildren is very likely to have this interest as well.

If there is an object or moral to this story it is that each generation will influence the one following it — and perhaps several generations more.

Fascinating and beautiful story, Thor… a joy to read… you can be very proud of them.

Pingback: Science or Sentiment | Thor's Life-Notes

Pingback: Stonehenge and Solitaire | Thor's Life-Notes