Eclipse Monday arrived and we proceeded as planned. Delicious French-pressed coffee and cinnamon rolls greeted our eclipse party guests, but the sky was covered in intermittent clouds, a mix of high and low layers, only occasionally offering a clear sunny view.

This did not seem to affect the group. They proceeded to continue their exploration of the campground and vicinity, logging birdcalls and trekking new hiking trails.

By the time the eclipse started, a little past noon, we all convened at our observing site. Cabin H, it turns out, is the only cabin at Zuber’s that had a full view of Old Baldy, and it provided us with a perfect open area in front to view the eclipsed sun!

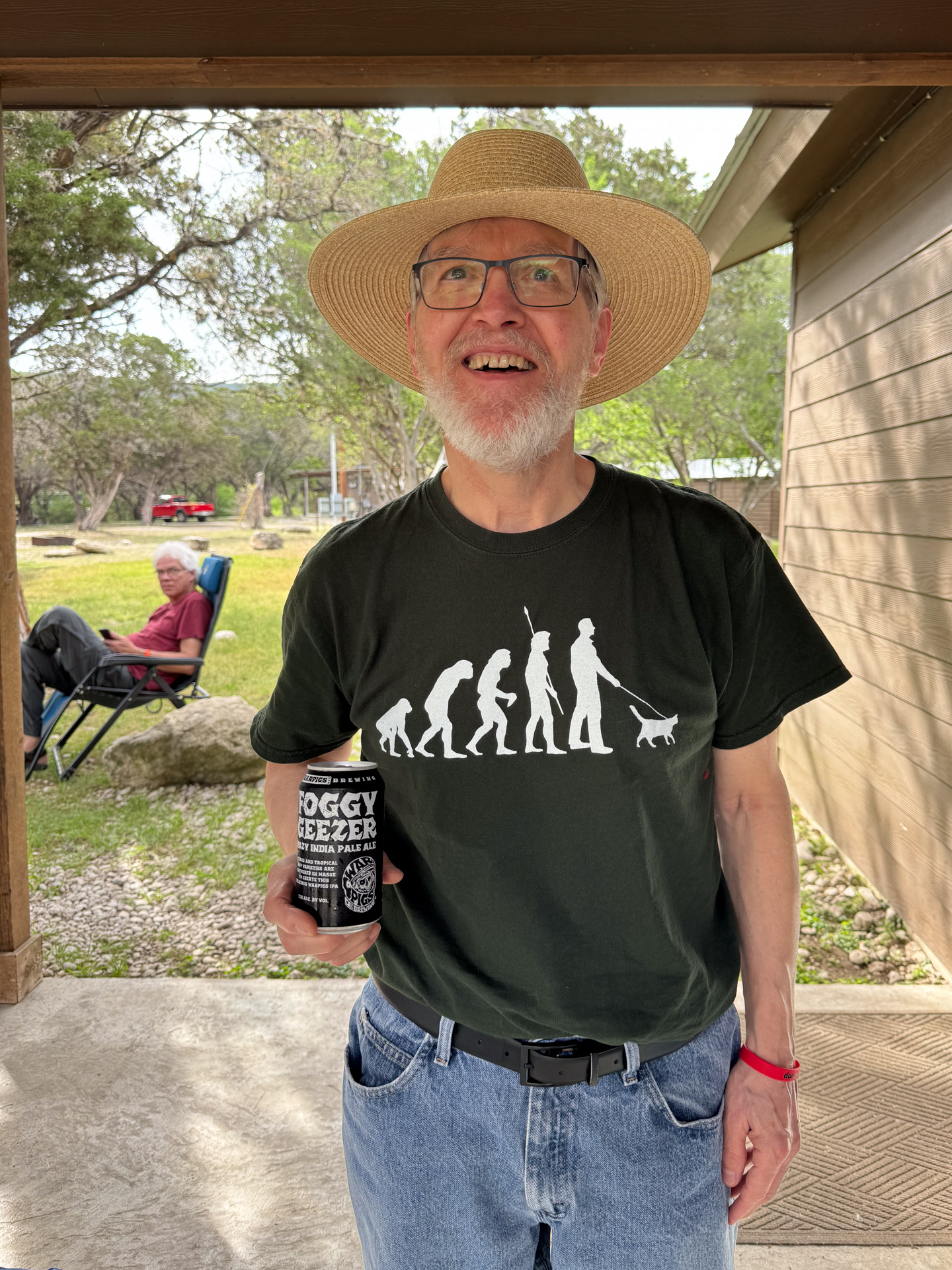

I had completed the setup of my cameras (more on this later). In principle, they were automated enough that I could relax and enjoy the show with my friends. I looked around and saw that our full group of black t-shirted eclipse observers had positioned their camp chairs to claim their personal view of the sky, making guesses about the sun’s location as it occasionally peeked through the clouds. Some had binoculars, properly filtered of course, and their punched name cards were near at hand.

Over on top of Old Baldy we could see the silhouettes of many people who had climbed it– to get a closer look, I guess. When they started striking odd poses and making wild gestures, I realized this was the gathering spot for the Wiccans and Druids. And sure enough, whenever the clouds presented an opening that showed a partially eclipsed sun, they could be heard whooping and hollering at it!

Continue reading