It has been discouraging to see the social disruption around us, the breakdown of norms, maybe a result of covid, but probably other forces as well. These ebbs and flows of how humans manage themselves are part of a longer-term story. Our individual experiences are part of a much smaller one, usually within a family with children, parents, and grandparents.

Some years ago, my dad sent me an article titled “The Stories That Bind Us.” It was interesting, but I took away only part of the message, which was that those children who had an awareness of their family history, by way of family stories, did better when they were released into the wild, er, I mean, into the world. The ups and downs, the achievements and setbacks, the triumphs and failures of older family members, became part of a narrative that demonstrated the arbitrariness of life events, and the pluck, resolve, and dedication of those family members to overcome such setbacks.

It’s a fascinating article, but I had forgotten some of the recommendations it made. I am always wary of correlations between some behavior and some outcome, say “people who do X, live longer than those who don’t”, where X can be anything, like “read a novel every week” or “be an amateur radio operator”. Somehow, I just don’t buy that if I read more fiction, or took up ham radio as a hobby, I would live longer as a result.

But in this case, there was an assessment tool, twenty questions, and there was a suggestion that family traditions contribute to the resilience we seek for our children. Traditions, even hokey ones, seem to instill a sense of stability and foundation in our kids.

So I was extremely pleased to host a “sausage-making party” shortly after Thanksgiving with Poldi’s and my combined families, this year including grandchildren! The last time we made sausage was seven years ago. Then Covid and other factors interfered.

This is a tradition that goes back many years in my family. My Swedish grandmother would anticipate the upcoming Christmas dinner she prepared every year, and make sure that she had a supply of Swedish sausage at hand. After all, her father would expect it to be on the plate right next to the lutefisk!

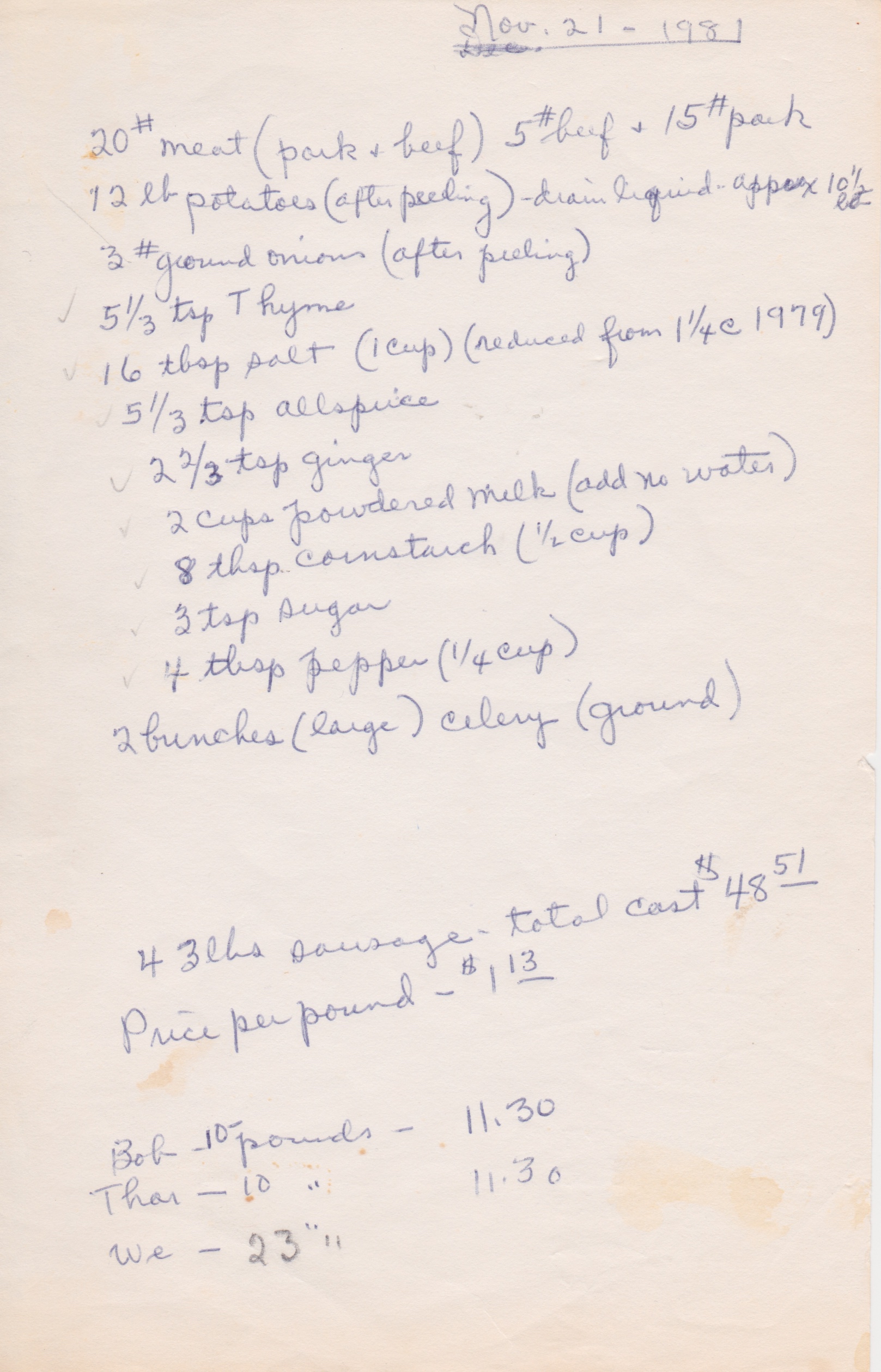

So she organized a sausage-making event every year, inviting her children and their families to participate, luring them with a delicious meal when the work was done. The sausage-making work itself required a coordination of tasks: the sausage casings (pig or cow intestines) needed to be rinsed and cleaned of their salt packing; the spices that provided the flavor, however minuscule, had to be measured and blended; the filler ingredients, potatoes, celery, and onions, had to be peeled, sliced, and chopped. And it all had to be blended into a mix of ground meat, usually pork and beef. There was a lot of labor involved in this project.

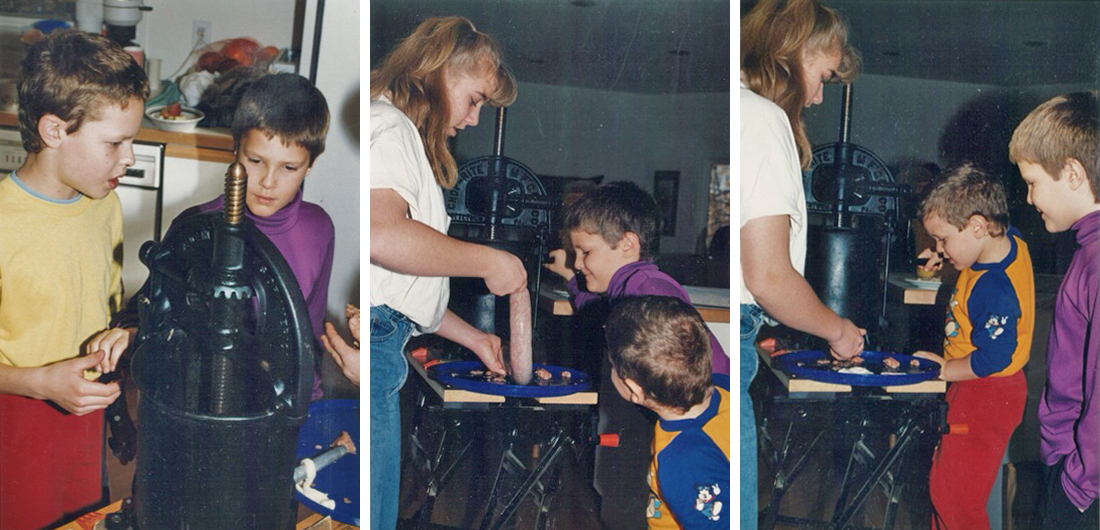

The climax of the event was when the ground meat, spices, and vegetables, mixed by the hands of grandchildren willing to get them messy, was placed in the sausage press, a large cast-iron cylinder with a giant crank and mechanical gears that drove a piston plate.

At this point, some finesse was involved. The casings were carefully applied and mounted onto the nozzle of the machine. And then the piston was cranked down into the press cylinder to force the meat through the nozzle into the casing. Two people were required for this task. A delicate balance of piston pressure and casing management was needed to make a proper sausage!

Most children don’t particularly care about the intestine casings (which involves touching them), but they all seem to enjoy turning the crank. So it is a frequent scene where the kids are taking turns at the crank, while a few adults are preparing the casings and pulling the sausages as the press squeezes the meat into them.

And this year, as we resumed this tradition, was no different. Kids being squeamish about guts, but curious about meat, is just exactly the thing that might make a mark in their memories.

I look forward to future sausage-making parties and the involvement of my grandchildren. Maybe it will contribute to their sense of family, that we are all part of their team, and give them confidence as they navigate their world. If so, I am happy to provide the hokey tradition that does it.