My dad’s younger brothers were favored uncles; they were grown-ups, yes, but they were fun. Bob, the youngest, was only a half-generation away from me. After spending a year in Viet Nam with the Navy, Bob had returned to Alameda California in 1972 to complete his service. He arranged for my brother Eric and me to spend time visiting him there during our spring break. The week with him was quite an adventure for us teenagers. It left a strong impression of California culture and provided an intimate look into the life of a highly regarded adult. We met the wonderful woman who would become our Aunt Karen. They planned to wed in June later that year.

Their wedding became a focus for the summer, and my dad arranged a complex family summer vacation to attend this event. We numbered seven, and were no longer small enough to all fit into our Volkswagen bug as we once had. Nor could we fit in the large Pontiac Bonneville, later known as the Great White Whale, especially since we were bringing camping gear for Dad’s planned post-wedding vacation activity: backpacking through Yosemite Park. So both vehicles were recruited for the cause. We had four licensed drivers in our clan and could tag-team the drive to California and back.

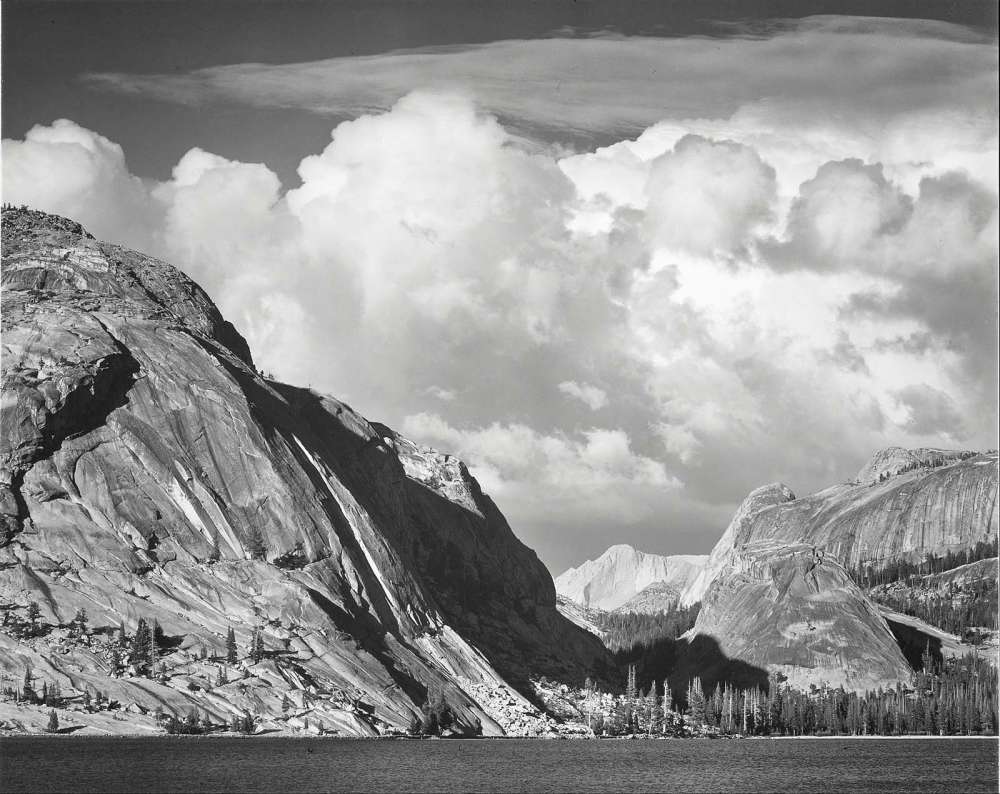

I described this backpacking adventure in a previous post. After that memorable experience, we continued by exploring Yosemite Valley. In addition to the famous views of Half Dome and El Capitan, there were art galleries! Yosemite was the adopted home of a number of artists, including photographer Ansel Adams, who had a studio and school here. Many of his images were on display and available for sale.

Continue reading