“Can I still do it?” and “Will I still enjoy it?”

I find myself asking these two questions about various activities I undertake. Now maybe you are thinking I am making oblique references to sex, but so far, that hasn’t been in the category of activities I am questioning.

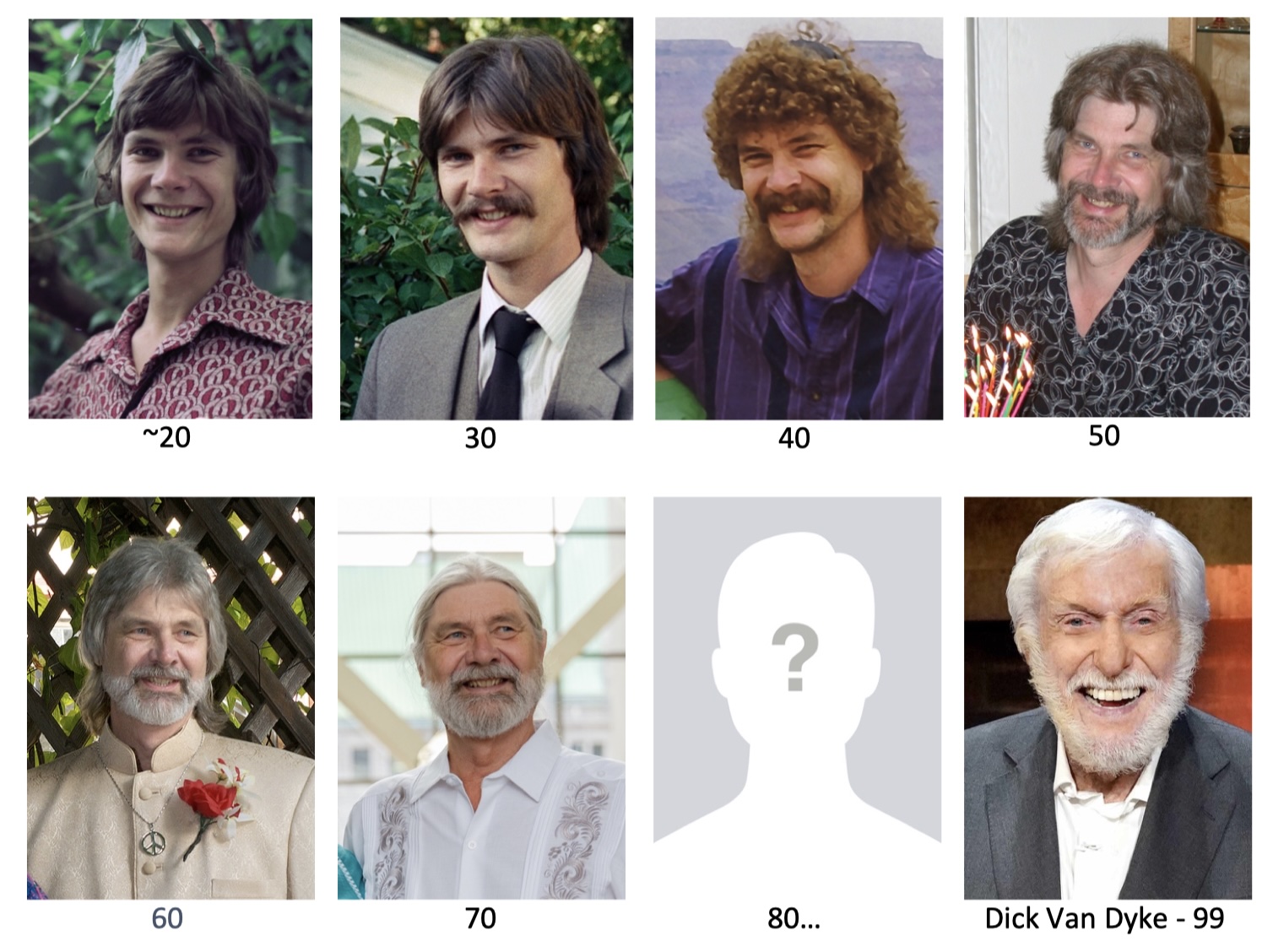

I noticed that, after turning 70, my superpowers appeared to be diminishing. This was a surprise to me because so far, at every decade mark, I had felt little difference from the previous one. There were a few things I suppose– certainly my appearance has changed as I have grayed, but for the most part, my capabilities have held.

Until now. I am starting to notice that my flexibility is less; I am stiff in the morning; my strength and stamina are diminished. Something has happened to the sinew and grit that powered my younger self. The analogy I entertain is: “the rubber bands are drying out”.

My limitations became apparent in a recent outing to take pictures of the night sky, an activity I have enjoyed for decades. One of my life highlights was recording pictures of the night sky on Racetrack Playa in Death Valley a few years ago. Currently, it is a similar trip with a hike to a collection of geologic features in the badlands of New Mexico. I treated it like many others I had undertaken, but this time, things felt different.

During my “Nightscape Odyssey” in 2001, I would survey a candidate night sky site during the day, making notes of how to get there, what compositions were promising, and generally getting familiar with the area. I would then return to the site later, as twilight approached, or sometimes even in the dark, and set up my telescopes and cameras. It made for a long day, and a long night, and I was usually exhausted the next morning. Nevertheless, after a morning nap, I would start the process all over again for the next night’s session.

This time, I was prematurely worn down after the initial reconnaissance and had to postpone the nighttime excursion until the next day. I didn’t expect that. Maybe it was the heat, or maybe it was the elevation, but those were factors before, and back then I still had the energy to carry on.

The lure of an image in your mind’s eye is a strong motivation, and I was very excited to see if I could capture the Milky Way behind the Alien Throne, my target for this outing. I described the overall experience previously, but I will now describe some of my other reactions as I undertook it.

I mentioned that my backpack was heavier than I expected. Yes, it had an excess of camera gear, but that was the payload. The rest was support: water, snacks, and protection against the desert night. The total came close to forty pounds, a typical number for a much longer trip. It was well within the range of packs I had carried before, and tonight I only had to go 1-1/2 miles over relatively flat terrain. I put it on, cinched the hip belt, and felt the familiar shift of my center of gravity as I took the first steps down the trail. It felt good to be doing this again.

As I continued, I noticed that I could feel the load in my legs. This was not a daypack. I could also sense some strain on my knees. This reminded me of an incident that happened a previous time I had carried this pack.

It was fifteen years ago. I had been on a weeklong backpacking trip, and on the last day, while climbing a ridge along the Lake Superior Hiking Trail, I experienced a sudden collapse of my right knee. It was truly a surprise; I fell to the ground. It wasn’t painful, my leg was just uselessly limp. My hiking buddies helped me back to my feet, but I couldn’t sustain the weight of the pack and collapsed again. Fortunately, it was only a short distance to our destination, and by distributing most of my load to the others, we were able to get there.

But here I was, hiking solo in a wilderness area as night approached. If the same thing happened, what would I do? I was a mile from my car, but to get there, I would have to abandon my load: $5000 of camera gear. Well, I guess I should factor that into my choice to embark on these excursions!

I carried on. And I carried the hiking poles that Poldi had lent me. I had always considered them a nuisance, getting in the way of my path and interfering with handling a camera, but I was now starting to appreciate them. They bore my weight and guided my traverse across the ruts and ridges in this rugged landscape. What was once an annoyance has now become a dependence.

I made it to the Valley of Dreams, following the route I had traveled the previous day, but the Alien Throne was another half mile through uncharted ridges and eroded gullies. I could see the destination on my GPS, but the terrain was not adequately shown. I found myself blocked by box canyons and cliffs. My strength was waning, the sun was setting, and I wondered how many more of these obstacles I could clamber over. If I became stuck, I would just make the best of things, taking pictures of whatever features were around me, even if they weren’t my prime target. It could still be a wonderful evening.

I was getting close, but a sudden drop-off was in the way. It was too high to scramble down, especially bearing my pack. So I removed the pack, lowered it over the edge, and then eased myself over and dropped down onto it. This was the last obstacle. I rounded the corner and found the Alien Throne! But it was not lost on me that this was an obstacle that in earlier days would not have presented a challenge. Further, had I not had a semi-graceful landing on my pack, what injuries would I have sustained?

I filed those thoughts away as I looked over the theater containing the Alien Throne. I needed some time to recover my breath after the stress and strain of navigating these eroded features, but I was aware that the light was rapidly changing. I needed to get my cameras set up.

This is a very pleasurable part of the adventure. I am finally at the site and can look for the compositions I have imagined. It is a mix of guidance and guesswork. I have some tools to help with orientation and timing, but it really takes placing an eye to the eyepiece to see how the landscape fits the sky. There are technical issues to resolve as well: exposure times, lens apertures, focus, and shutter intervals. These keep me narrowly focused on my goals and shut out any other concerns (I’m oblivious of the need to worry about scorpions).

But as I placed each camera and tripod in its place, I could not help but notice each difficult position, and each awkward angle I had to assume in doing so. Yes, the terrain is uneven, and the viewpoint requires the right height and angle, whatever it needs to be for the composition, but I don’t remember it being such a physical strain to achieve it.

Kneeling is a particular motion, required for just about any adjustment. I find that it is hard to get back up. And when I drop something, it becomes a major project to recover it. The aches and pains of drying rubber bands were making themselves known in this otherwise pleasurable setting.

But when the cameras are each in place and running, I heave a sigh and settle in for a night of watching the heavens flow across the sky. It will be an hour or more before the cameras need attention. This is another pleasant part of the nightscape adventure. I record the photographic details of my experiments in a notebook and contemplate what the outcomes might be, and what subsequent exposure tests I should undertake. When I am with Poldi, we find spiritual and intimate activities to fill the time under the stars, but on this night I am alone, at least for a while. Soon after my cameras were set up, another night sky photographer arrives. We share our stories while the stars move above us.

We eventually retreat to our refuge against the cold desert night. I am in a sleeping bag tucked into a recess in the rocks. I relax here, watching the sky above and listening. There is a cricket chirping. I am astounded at how loud it is, and then I remember, I now have “bionic ears,” recently acquired hearing aids, another indicator of crossing the seven-decade threshold. They have been tuned to amplify the high frequencies that I was previously missing. This helps me to understand the speech of women and children, but it really helps me to notice the frequency of cricket chirps, which are slowing as the temperature drops. The chirps keep me awake.

But eventually they stop, or maybe I drift off. When my alarm goes off for the next exposure event, I climb out of the sleeping bag and stumble toward the camera that needs attention. The moon has set, and it is now purely starlight that guides me. Plus my flashlight, because starlight is just not enough, at least on this uneven terrain. As I navigate over the rocks toward the camera, I recognize the precariousness of my path. At home, at night, in the dark, I must sometimes navigate to the bathroom. It is much easier with a nightlight– so we have installed them. Here, in the certified dark sky wilderness of New Mexico, I am on my own. I am aware and notice the uncertainty of my steps on the sandstone terrain. Loose gravel and vegetation contribute to the hazard. Once again, I recognized that if I fell and was injured on one of these camera servicing missions, I would no longer be enjoying the night.

But the cameras, with their new exposure settings and refreshed batteries, continue their nighttime schedule. I return to my nook to marvel at the Milky Way, now high in the sky. The cricket reminded me that I have bionic ears, but the sky reminds me that I also have enhanced eyesight.

The miracles of modern optics can correct for obscure vision conditions, including astigmatism and other aberrations. I put on my progressive prescription glasses so that I could appreciate the full glory of the night sky, beyond my now compromised seventy-year-old built-in lenses. It was a bust. For whatever reason, my glasses made the view worse, not better. I will be investigating this failure, but in the meantime, I enjoyed the night sky without optical assistance.

The pleasures of the night continued; the cameras were serviced despite the risks, and eventually the sky began to lighten. Dawn was approaching.

The exposure schedule ended as the sun rose, and I gathered my equipment, preparing for the hike back. The night before, I had reached my destination just before my strength ran out. Now, after a night to recover, I expected an easy hike. I knew the way. And it started that way, but soon became hard.

It was not a difficult trail, mostly level. And the sun was still low, the temperature moderate. The path was easy, but on encountering the slight banks in and out of a dry creek wash, I was annoyed that I could not just scramble them; I had to take carefully placed steps.

Only a mile and a half back to my car. Yet, I found my feet becoming “heavy”, without the lift to rise ever slightly for the next step. And they were sloppily planted in that next step. It was the closest thing to a stagger, and I realized it.

So I paused for a rest, dropping my pack for a while. Sitting on a rock and taking some water, one of my hiking poles fell to the ground. I cursed. Now I would have to bend over to get it. When did just stooping down become such a pain? I have never enjoyed getting under the desk to plug in computer or power cables, but just bending over to pick up something I dropped? That’s new.

Reaching the point of involuntarily dragging my feet was a new experience, a physical regime I was unfamiliar with. It made me appreciate the limits that people sometimes overcome, not just for recreation, but for survival.

And it added to my list of items to balance against the pleasures of my remote outings. I really enjoyed the hours in the desert monitoring cameras and watching the galaxy cross the sky. But I have become aware of the risks I am taking on, some of which seem to have increased over my years.

I was halfway back. I was aware of the remaining distance, which was more than the physical distance. It included the depletion of my energy reserves. I may have been staggering, but I was not to the point of stopping. I hoisted the pack and continued back to the car.

I can now declare that “I can still do it”, and I will also declare that “I still enjoy it”, but I must temper this last statement by acknowledging that the enjoyment is diminished by the increased risks I take on.

Life is filled with tradeoffs.

It may seem that I am complaining about getting old, and I guess I am, but I am also thrilled that I am still around to do so.

Thor

Don’t feel like the Lone Ranger. I had the same awakening about 76. And then things really began to happen, Now at 78, soon to hit 79, I’ve become that image I remember when my father became an “Old Man”. Loss of body mass and muscle iis obvious. The gray matter still seems to be in clickin, I look in the mirror each morning and wonder who that old guy is and where did the other guy go.

The good news is I’m healthy and have great genes. Dad made it 90 and Mom was 99. So, I hope your like me cause I’m gonna be around for a long time.