I was moved recently by an unexpected item encountered while clearing out my parents’ home. They both passed away in recent years leaving, as we all will, a lifetime of accumulated possessions. Perhaps it is a rite of passage that we all mark our parents’ passing with tributes and shared memories, and then respectfully distribute their earthly possessions.

Those possessions usually include home furnishings of a previous era, and clothing that might fit but doesn’t match anyone’s current style or fashion. Many kitchen utensils will find their way to donation centers. Easy items to dispatch are those for which there are few memories. The more difficult are those with sentimental attachments.

My dad was an amateur radio operator, a “ham”, which is a term for the enthusiasts across the world that participate in this form of communication, ever since Marconi sent his first wireless message. There is a broad and varied number of these practitioners of a discipline that requires technical expertise and skill, and a desire to share their experiences “over the air”.

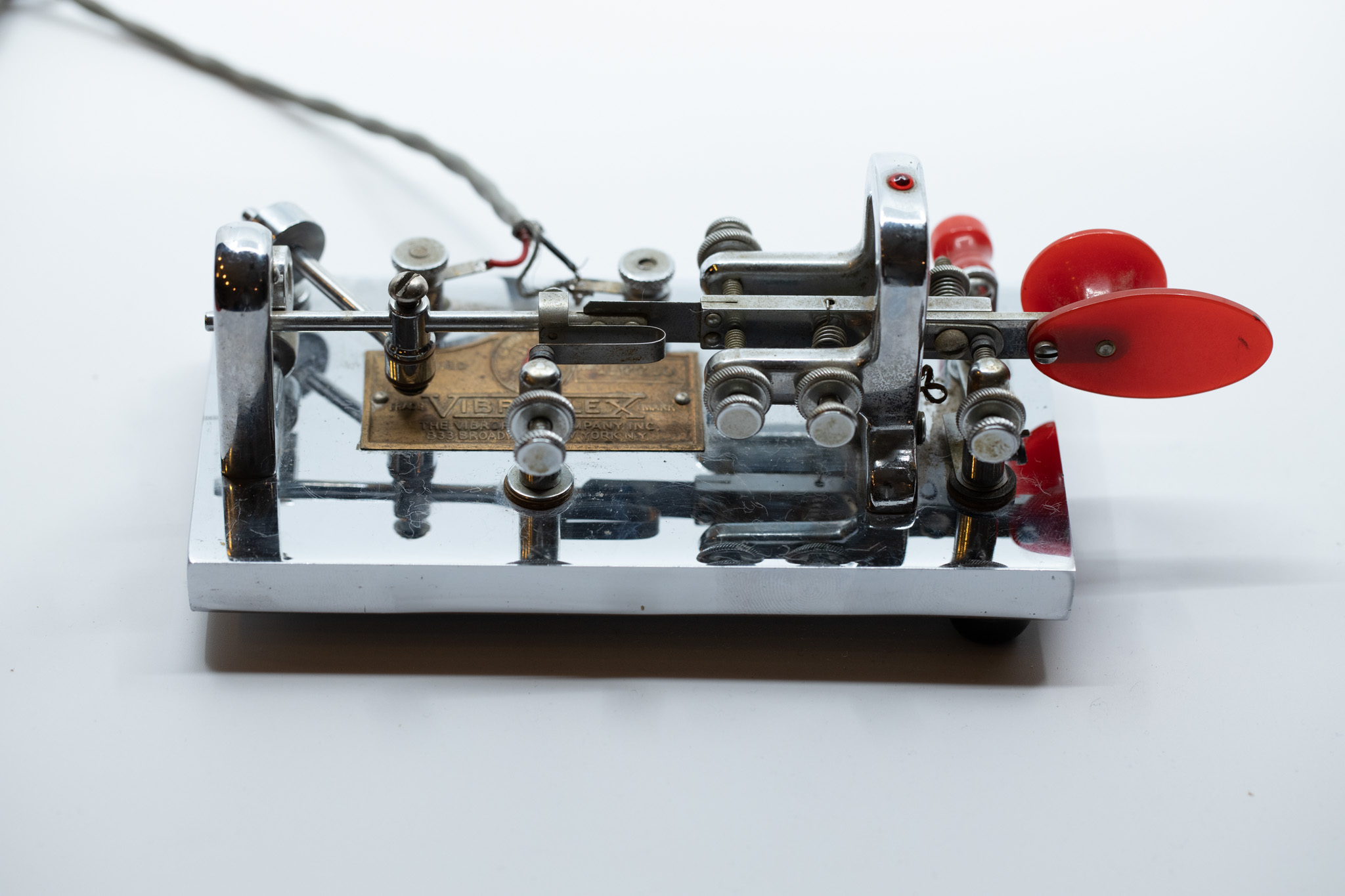

I grew up in this culture, listening to the chirps and squawks of my dad’s radio receiver late into the nights. One of the essential ham skills was to tap out Morse code messages with a telegraph key — the first level of an amateur radio license (“Novice Class”) required proficiency at five words a minute. My dad was extremely skilled at this and could signal at much higher rates. As one improved in this skill, the limitations moved from brain-hand coordination to the mechanical key itself.

This limitation was recognized early on, and various ingenious adaptations of the simple momentary contact key were invented. Some worked better than others. Over the course of my dad’s ham career he acquired various makes and models of telegraph keys with which he competed in amateur radio contests, to see who could make contact with the most other hams in a weekend.

His amateur radio station equipment will find homes with other ham operators, but his set of telegraph keys were distributed to his children, all of whom have those memories of dot-dash Morse code beeps in the night. This is the item I received: on a beautiful chrome-plated base, the key itself is a delicate collection of mechanical components, carefully balanced and customized to the hand of the operator. I am told that operators have a distinct “signature” that can be recognized when listening to the delivery of Morse code, each hand having its own rhythm and style.

The ham community has an endearing term of respect for their fellow amateurs who have since passed away: Silent Key. It is a reference to the early days of telegraphy where the letters SK were sent to designate the end of a transmission, and then the station would become silent.

There is a national silent key registry, the cumulative obituaries of the ham community, where you can look up life accounts of past amateurs, including my dad, K0TO.

His station is silent now, but my memories of it will remain until I too become silent.